Fast-tracked funding

To expedite campus response to pandemic, UCI leadership amasses $2.5 million for COVID-19 research projects

In mid-March, COVID-19 was sweeping the country and lockdowns were just beginning. Medical researchers and public health professionals were scrambling to not only make sense of the virus but figure out a response that could save lives.

Normally, research at universities nationwide moves at a deliberate pace, with funding dispensed after lengthy application periods, ensuring maximum fairness and time to conduct extensive review processes. But the pace of the COVID-19 pandemic was fast, chaotic and anything but deliberate. Researchers needed to act fast.

Across the UCI campus, faculty from every background – medical researchers to artificial intelligence specialists to physicists – knew they had something to contribute to the fight against the coronavirus. All they needed was a little help.

“The breadth and depth of UCI’s research expertise is truly impressive. So when it came time to confront the COVID-19 crisis head-on, we knew the most helpful thing we could do was give our researchers a jump-start with some seed funding,” says Pramod Khargonekar, UCI’s vice chancellor for research. “We know that such funded projects really have the potential to lead to major advances and turn the tide against COVID-19.”

The idea for a research fund to enable these endeavors first sprouted at UCI’s School of Medicine. Dean Michael J. Stamos, M.D., thought that if investigators were granted seed money, they could focus on projects aimed at expediting a response to the pandemic. He chose to allocate $300,000 for a fund dedicated to COVID-19-related efforts to treat or control the spread of the disease. The medical school’s research committee donated an additional $100,000.

Khargonekar pledged to match the school’s contribution. He and Stamos began reaching out to deans at other schools across campus to see if they would add to the fund. All told, the team pulled together $1.25 million. Then, the John and Mary Tu Foundation matched that amount, bringing the total to $2.5 million, surpassing the $2 million allocated by the University of California Office of the President for the whole UC system. The UCI Joint Research Fund was formed.

“That’s an amount of money where you can make a real impact – and we wanted to make sure we used it well,” says Suzanne Sandmeyer, vice dean for research at the School of Medicine. “It became abundantly clear that we needed to set up a structure to transfer these incredible resources into the hands of investigators in a really effective way so they could do their best work quickly.”

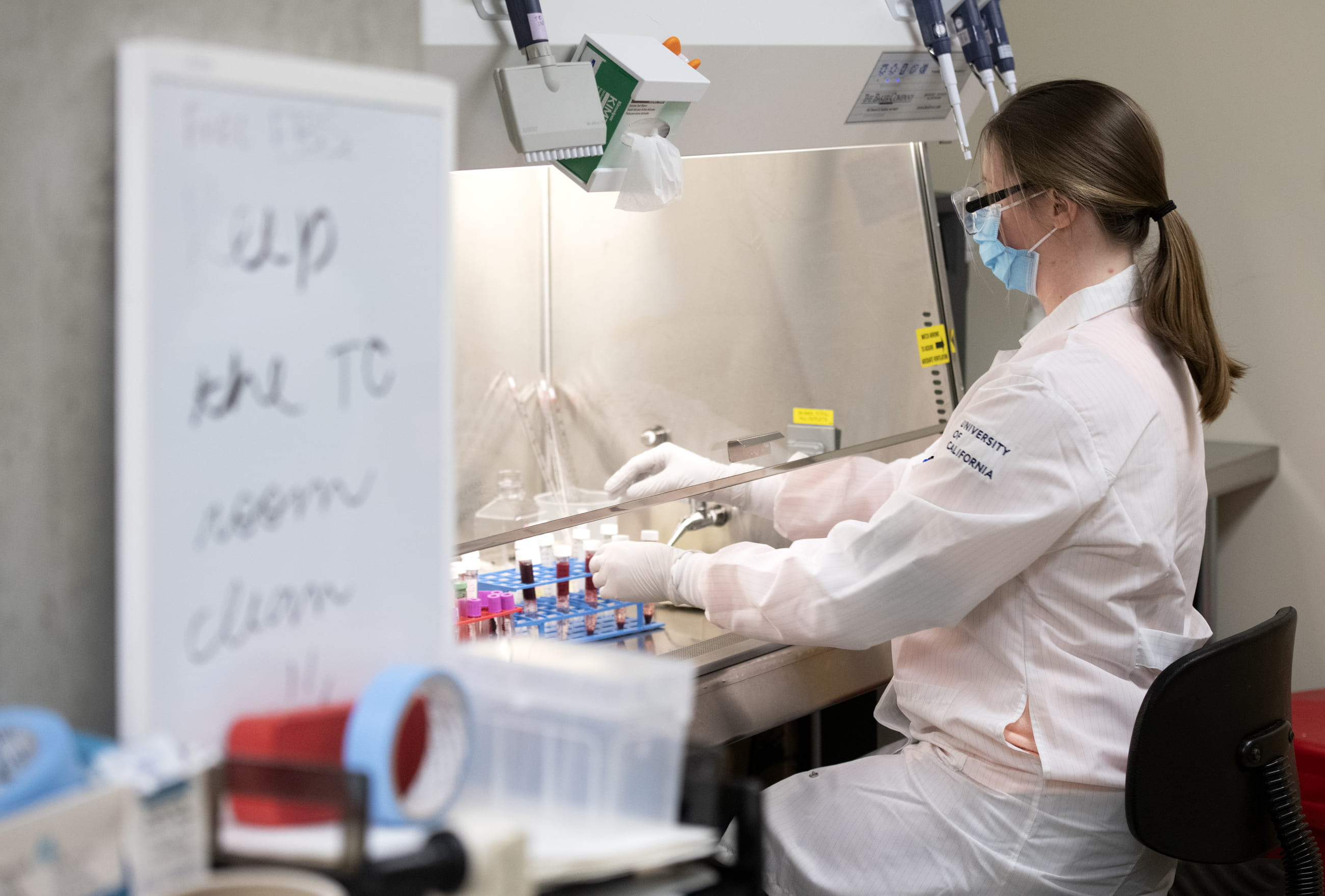

So UCI established a process to solicit and vet project proposals from researchers. A panel of senior investigators created the Clinical Research Acceleration and Facilitation Team-COVID Committee to evaluate the dozens of proposals that had started to fill up the pipeline. The panel scores them using the same mechanism as the National Institutes of Health to ensure that funding allocation is fair and equitable. Proposals for clinical trials go through a modified review process.

Grants are capped at $60,000, unless investigators can clearly demonstrate the need for more. So far, over 50 proposals have been submitted, and 16 have already been funded, receiving a total of about $800,000.

UCI medical researchers who partner with community organizations can apply for separate seed funding from the Campus-Community Research Incubator Program at the Institute for Clinical & Translational Science, which has set aside an additional $20,000 for coronavirus-related research projects. The small grants – $5,000 for capacity building or $10,000 for pilot projects – are meant to foster cooperation between community healthcare agencies or nonprofit healthcare safety net providers. The review process is similar to that of the NIH, and applications for the next round of grants are due June 1.

“If you’re going to do research meant to improve lives, you’re going to be much more effective if you include the community and the public in helping guide your research,” says Robynn Zender, a community health research representative at the ICTS. “A lot of times, universities are seen as removed and inaccessible, but these grants help faculty collaborate with community leaders on research. It’s a win-win of information exchange and relationship building and trust.”

Projects for UCI’s larger, COVID-19 Joint Research Fund are quickly getting approval – and results.

They address a wide array of issues related to the disease, from face mask design to COVID-19 antibody detection to virus prevalence among healthcare workers. One particularly compelling project is using a predictive algorithm to analyze patient intake data and look for patterns that could indicate which individuals are likely to become critically ill from COVID-19 and which will only be moderately sickened. The project will track 10 parameters to predict at-risk patients.

“We know that one of the odd features of this disease is that patients can go from being virtually asymptomatic to being critically ill in just a short period of time. We need to know why some people suffer from this and others don’t. This particular project will help determine what those factors are,” Sandmeyer says. “The idea is that you can send people home even if they test positive because they’re unlikely to be critically affected and keep asymptomatic people under care if they are likely to get quite ill.”

Another project that has received seed funding seeks to develop a more robust antibody test that will simultaneously examine 250 separate antigens for various proteins associated with viruses from SARS to MERS to COVID-19 to everyday colds. This panel of antigen assays has a low rate of both false negatives and false positives – meaning that it’s almost always accurate in identifying people who have COVID-19 antibodies.

The UCI Joint Research Fund encourages researchers to reach across disciplinary boundaries and combine their individual areas of expertise to generate new discoveries. For instance, physics professors who normally study particle detection are partnering with School of Medicine researchers who usually examine particulate pollution to learn how the virus is inhaled.

“We don’t want people to pivot from their area of expertise and become obsessed with COVID-19 and not do things that they were trained for many years to do,” Sandmeyer says. “But the virus is so complicated – and its effects on the body and society are so complicated – that many areas of research are touched by it. Everyone has something to contribute.”