Putting down roots in the tropics

Generous alumni gift guarantees UCI access to tropical studies program.

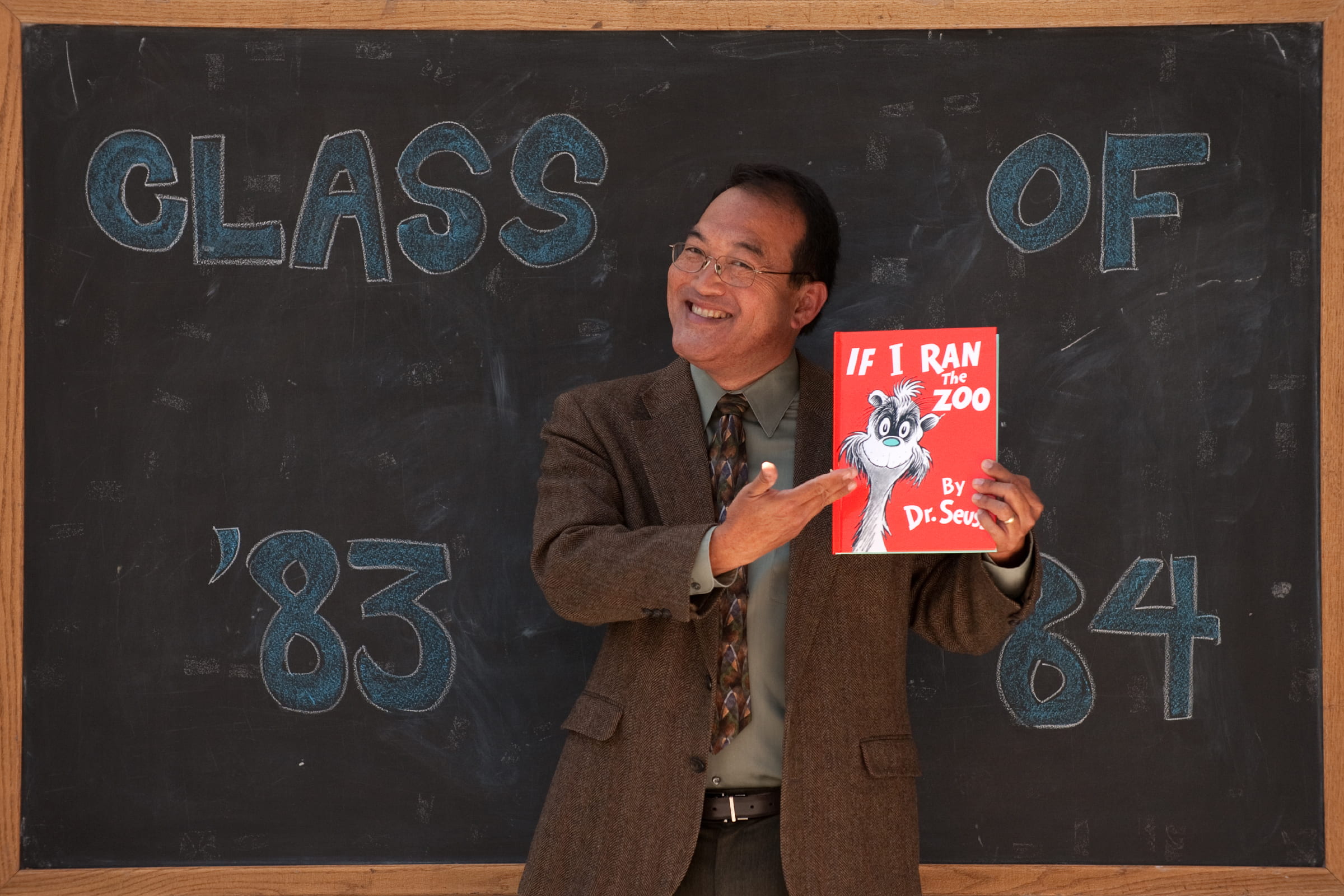

UC Irvine’s membership in a highly-regarded international tropical studies program is guaranteed forever thanks to a generous gift from alumnus Brian Atwood ’74 in honor of his favorite teacher, ecology & evolutionary biology professor Lynn Carpenter.

“The best way I can sum it up is Lynn taught me how to think,” said Atwood, managing director of Silicon Valley-based Versant Ventures, and a member of the UC Irvine Chief Executive Roundtable.

Atwood spent much of his senior year with fellow senior Preston Johns trapping and cataloguing rodents on a Tehachapi mountain peak as rising waters from a huge new dam slowly surrounded it. Carpenter not only encouraged their desire to tackle the project on an emerging ecological island, but taught them research skills, writing and statistics, all of which Atwood says have helped him in his career as a venture capitalist. “She was always collaborative, but firm,” he says.

His donation in Carpenter’s name will fund lifetime membership in the Organization for Tropical Studies, headquartered at Duke University, through which more than 300 scientists from 25 countries work at field sites in Costa Rica and Africa each year. When school of biological sciences Dean Al Bennett told him at an alumni dinner that UCI’s participation was in jeopardy, he instantly offered his support.

“I was so excited to find out a private donor was going to pay the fees,” Carpenter says “When I heard it was Brian, and he was going to do it in honor of me, I was stunned. He was one of my first students 39 years ago, and he thought outside the box. His project tested cutting-edge ideas about island biogeography.”

Atwood’s financial support is crucial right now, she says, as tropical studies take on critical importance. “The fastest rates of human population growth and destruction of the resources that service human population are occurring there,” she says, “and between population growth and environmental degradation, it is a global crisis in the making.”

Graduate students and faculty have traveled for decades to Organization for Tropical Studies research stations, where projects and classes in the rain forest have nurtured critical work, lifelong friendships and even romance. The organization recently began undergraduate programs as well.

“We were really on edge about whether we could afford the $10,000 annual membership fee,” says Bennett. “It’s an incredible program, you are right there in the forest, able to do sophisticated research with colleagues from around the world. This generous gift guarantees UCI will have access to critical education abroad without having to rely on government funding.”

Carpenter began work in the tropics in 1968. Her focus on restoration ecology grew from her concerns about coffee farming and clear cutting. She has mentored many students at OTS’s Las Cruces research station in Costa Rica, and on adjoining land she owns. She served on the organization’s board of directors for years, and when necessary dug into her own pocket to help pay UCI’s way.

Kailen Mooney, currently UCI’s delegate to OTS, convinced the organization to set up lifetime memberships. He said “it is extremely gratifying” to be the first campus to take advantage of it. Mooney, an assistant professor of ecology & evolutionary biology, said his work with the organization was a crucial step in his intellectual development as a scientist.

Kristin Smock, who did research at the station in 2008, says the membership fee is no academic matter. As a researcher from a member institution, it cost her $35 a day to stay and work at OTS facilities in 2008. Otherwise costs would have soared to $5,000 or more for eight weeks, impossible for her and other struggling graduate students.

“I could have never completed my doctorate without the resources and support provided by the Organization for Tropical Studies,” Smock says. “The station is incredible, and I was able to meet some of the biggest names in tropical biology and learn from excellent mentors.”

Smock, now a biology lecturer at Ohio State University, tells students about the doctoral work she did from 2003 to 2009 under Carpenter’s tutelage, studying “nurse trees” rich in nutrients needed to nurture the forest back to life. “They love it. They all want to go save the rain forest,” she says.

Lifelong relationships are another recurring refrain from participants who spend weeks living and working in close quarters. For Riley Pratt and Jessica Gleffe, the bond proved especially strong. He was a UCI doctoral student and she was a master’s student at North Carolina State University when they met at the 2004 summer tropical ecology field course. They shared their first kiss in a huge fig tree in Costa Rica. In 2006 he insisted they return to the same tree, and proposed marriage. She said yes.