Tracking social media’s role in Egyptian uprising

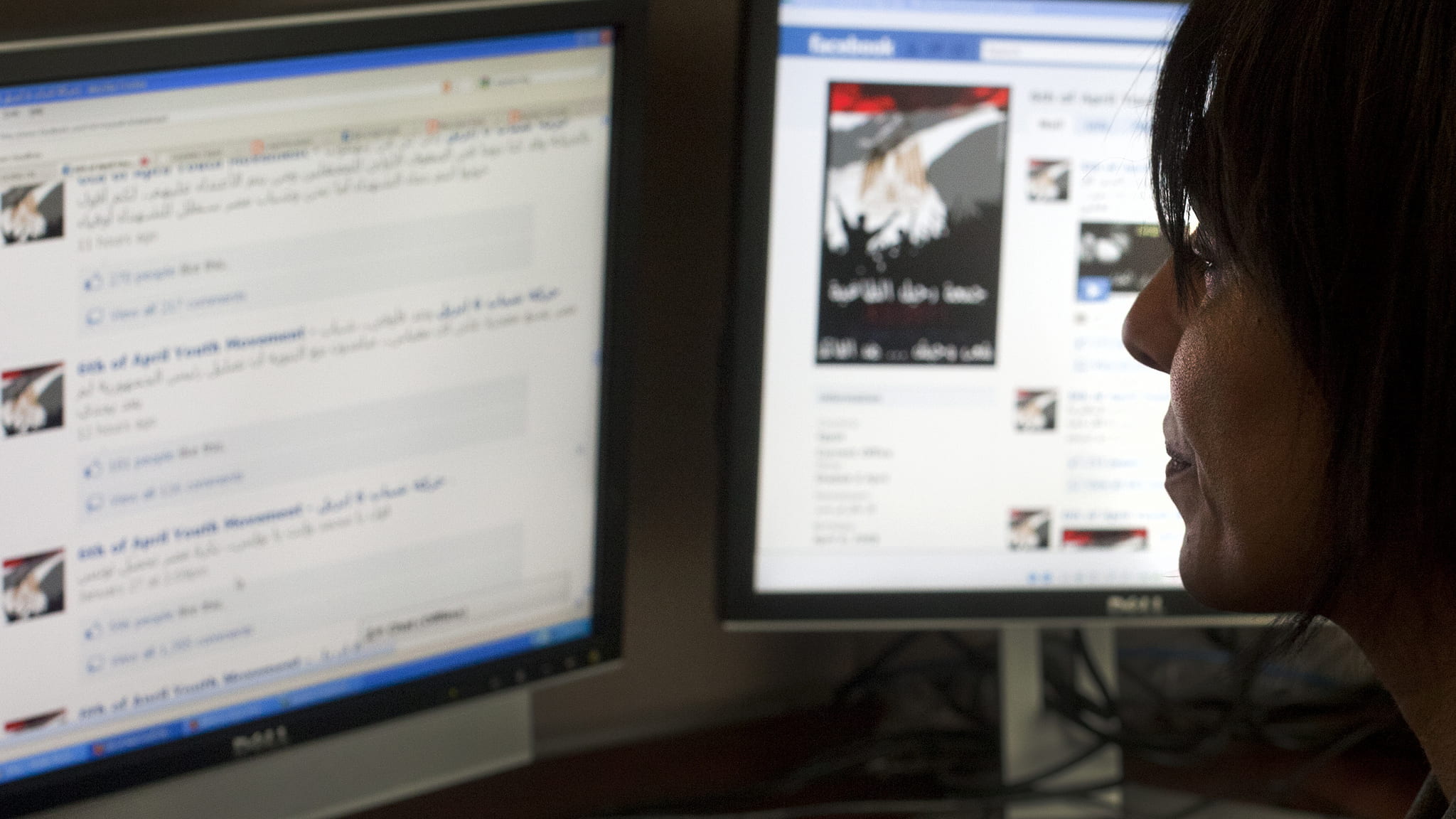

UCI researcher Ban Al-Ani tracks role of social media in Egyptian uprising.

Drink juice before you go; it will give you energy and keep you hydrated. Carry two cell phones. Take pictures with one in your left hand, then slide it in your pocket and – if asked – give police the one in your right hand. And yes, after completing weekly prayers, it’s important that you turn out to unseat Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.

These are a few of the online tips and posts that helped propel what could have been another halfhearted Cairo demonstration into a full-throated uprising with the potential to shift the balance of power in the Middle East, according to Ban Al-Ani, a research scientist at UC Irvine’s Donald Bren School of Information & Computer Sciences.

Al-Ani found that within days of demonstrations in Tunisia, posts were drawing parallels with the repressive Egyptian government. By Jan. 15, there were online threads calling for the Jan. 25 protest in Cairo – including tips on how to gather, as well as where and when.

Equally important, she says, are the posts that lay out reasons why a rational person might not want to take to the streets, then offer explanations for why it’s necessary and could be effective. Al-Ani says there does not appear to be one organization choreographing the online efforts. “Maybe there’s one group on high fooling us all,” she says, “but I haven’t seen evidence of that.”

Unlike many, she was not surprised by Mubarak’s imposition of a “virtual curfew” and shutdown of the Internet. “I was surprised it took him so long; Saddam would have been all over that in a flash,” Al-Ani says, referring to former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

She knows Mubarak is in his 80s and perhaps not computer-savvy but notes that he must have close advisers monitoring the same sites she does. Al-Ani speculates that perhaps they expected the protests to fizzle, as they have in the past.

One Facebook page she has been reading is named for just such an event: 6th of April Youth Movement. “That was April 6, 2008,” Al-Ani explains. “There was a demonstration in Cairo, but it faded away.”

In the years since, the group’s Facebook posts have often been lines of poetry or traditional Egyptian folklore or art. That changed abruptly in mid-January, when the Tunisian uprisings began. Posts calling for the Jan. 25 demonstration were quickly followed by posts for more mass gatherings.

“Tomorrow Egypt will follow Tunis” reads part of the last entry on Jan. 27, the day Mubarak pulled the plug. Al-Ani observes that the authors used local-dialect script for the word “Egypt” and formal Arabic for the rest and that they invoke a Muslim leader and a Christian saint in another part of the post.

The site, like many, has scrupulously sought to avoid casting the uprising as the work of one religious, ideological or political group. “That is heartening to me but also worries me at a personal level,” Al-Ani says. “They don’t appear to be organized for the next step.”

Six days later, the Egyptian Internet and the page are back up. Al-Ani translates the first post in her campus office: “They promised, and they kept their promise. The youth of Egypt are creating a miracle by anyone’s measure, ensuring all attempts to lead us astray by the president of the republic are no longer valid.”

Within minutes, the post has 184 “likes” and 127 comments. But the page’s profile photo has changed from a man shaking his fist at the sky to a line of marchers, with ominous script reading “For the blood of our martyrs.” That night, news reports show the bodies of dead demonstrators being dragged across a Cairo bridge.

Al-Ani and her colleagues have already applied for funding to study the past month’s events. “It’s been a long time since we had a real revolution,” she says.