Tracking precipitation planetwide

Team creates online maps used by foreign countries to predict – and prepare for – intense rainfall.

UC Irvine engineering professor Soroosh Sorooshian spent the holiday break closely monitoring the heavy rains – not just at home but half a world away. Unlike local forecasters, he and his colleagues aim to help whole nations grapple with deluges.

“Some climate modellers predicted drought for Southern California, and instead we exceeded a year’s worth in a week,” he says, pointing to intense red and orange rainfall concentrations on a Google map of the Earth. “Australia’s been getting lots too.”

Sorooshian, director of UCI’s Center for Hydrometeorology & Remote Sensing, can tell at a glance how much rain is falling across the entire planet. His team can also supply data that zooms in to a level of 16 square kilometers, showing not only that it’s raining in Japan but that somewhere in Kyoto an area roughly the size of the UCI campus is being drenched. Best of all, the information can be accessed by anyone at no cost and can be widely shared.

Working with the United Nations’ science arm (UNESCO) and U.S. agencies like NASA and the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, Sorooshian and his colleagues produce online maps and other data increasingly used by governments to foresee where and when heavy rain will hit and to brace for possible floods, mudslides and other disasters. Several countries in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Middle East utilize the center’s work.

“What we provide, essentially, is the fuel for hydrologic models that can predict things like the extent and timing of flooding downstream,” says Sorooshian, Distinguished Professor of civil & environmental engineering and Earth system science.

Referring to the monster monsoons that strayed last fall from their normal course over India to hammer poor, remote reaches of Pakistan, he says: “If Pakistan had been able to see the patterns of water from far off, it could have better prepared and saved many lives and livestock. It’s similar to what happened after the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia; now an early warning system is in place. These things are very important.”

Sorooshian was recently awarded an international prize for water resources management and protection by Saudi Crown Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz. But by temperament and vocation, he’s not inclined to boast. “All these professors and their awards!” he says, laughing. “I’m interested in what works and how we can help people, not purely theory.”

A native of Iran, Sorooshian came to the U.S. to study at California Polytechnic State University and UCLA. His first love was aerospace engineering, but his career took an abrupt turn when a UCLA professor told him and a second student that the fellowships he’d promised them had been cancelled.

“We were standing in the hallway cursing in Farsi, wondering what to do,” Sorooshian recalls. Another Iranian graduate student who spoke the language overheard and invited the two to his office and convinced them to switch majors to systems engineering.

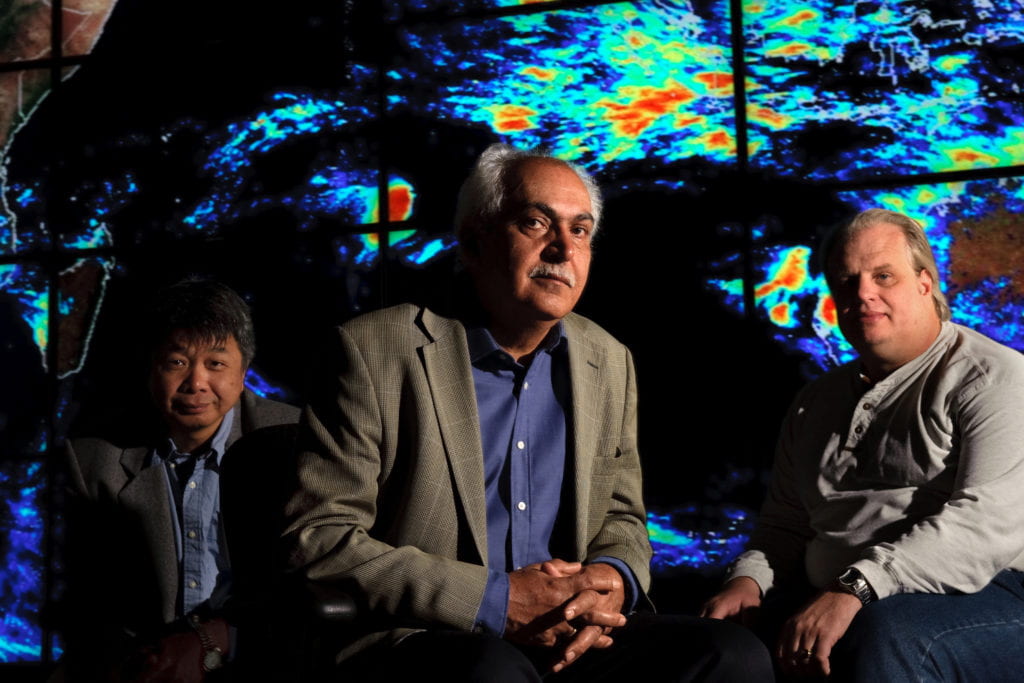

Sorooshian ended up at the University of Arizona, where he stayed for 20 years. In 2003, he accepted a position at UCI and brought many of his top staff with him, including Kuo-lin Hsu. The associate adjunct professor of civil & environmental engineering developed the algorithms employed by the hydrometeorology center to effectively monitor continuous rainfall amounts.

“Through the use of a mathematical modeling approach known as artificial neural networks , we process different electromagnetic signals picked up by satellites from clouds and storm systems, convert them into rain estimates and show them as these images,” Hsu explains.

“These images aren’t clouds,” adds Sorooshian, looking at a brightly colored rainfall concentration map on his computer screen. “It’s more like a cooked dish: You go to the grocery store and buy individual items, then combine them into a dish. This is rainfall around the world for the last 48 hours, captured one hour and 38 minutes ago.”