Science, stem cells and serendipity

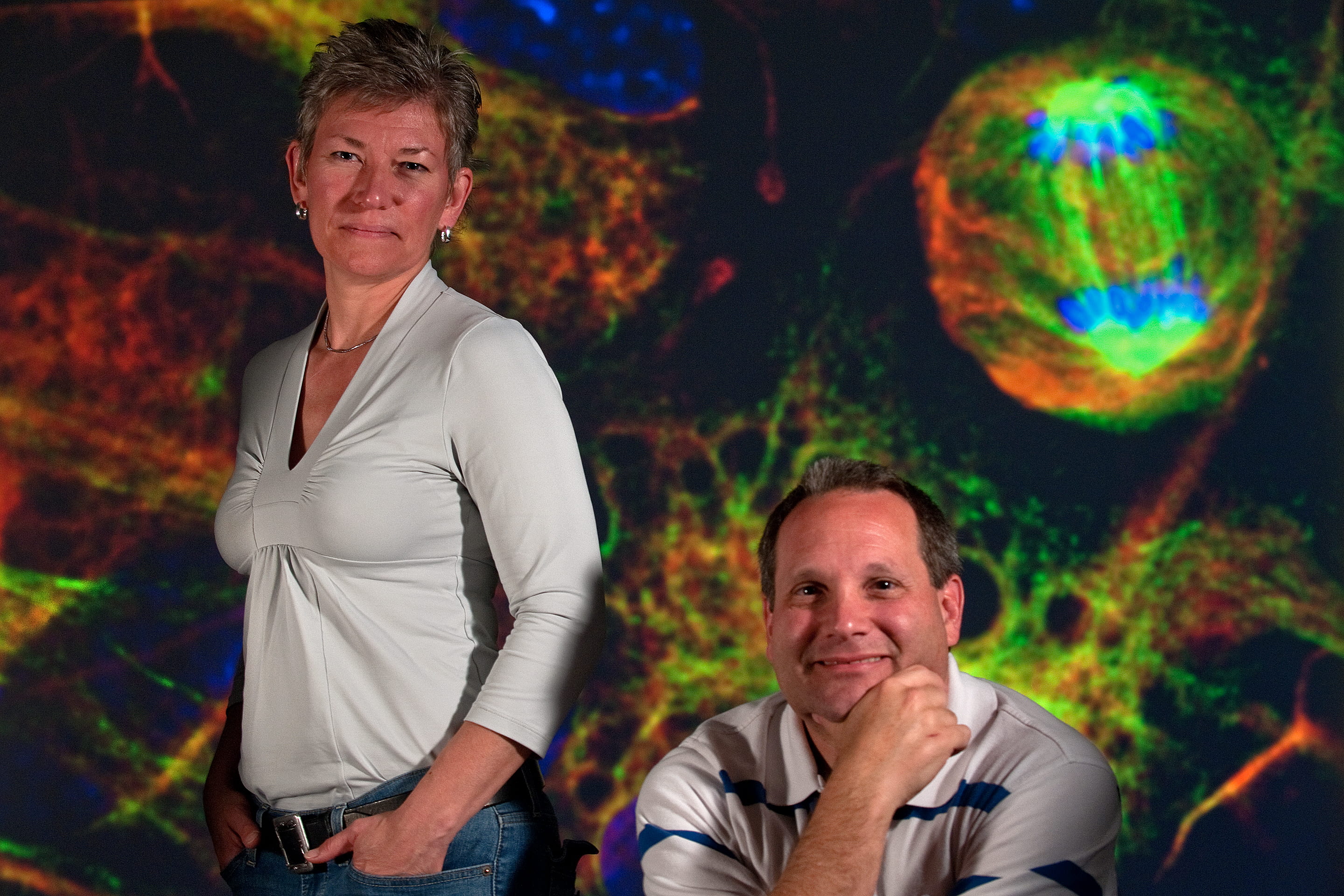

Serendipity has played a great part in the careers and personal lives of Aileen Anderson and Brian Cummings, the UC Irvine husband-and-wife team that has helped move stem cell therapy for spinal cord injury a giant step forward.

They met as undergraduates at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Cummings would visit his then-girlfriend in her dorm, and by coincidence Anderson lived on the same floor. “If I’d gotten into Cornell, it would have been a whole other story,” she jokes. “And I’d be splitting wood in Illinois,” he adds. The two were united by their mutual enjoyment of Dungeons & Dragons — and science.

Both got their doctorates from UCI, Anderson in biology in 1995 and Cummings in psychobiology in 1993. Both now work on campus as associate professors of physical medicine & rehabilitation and anatomy & neurobiology. And both participate in pioneering work at UCI’s Sue & Bill Gross Stem Cell Research Center.

The couple, in collaboration with StemCells Inc., developed a treatment for spinal cord injury that uses human neural stem cells. The procedure proved effective in mice and is now being tested in humans. Anderson and Cummings, who have adjacent offices in Gross Hall, recently sat down to discuss their partnership, their progress in the field of nerve regeneration, and the serendipity that led to their scientific success.

Your study was the first to show that human neural stem cells can restore mobility in mice with spinal cord injury. How did you wind up working together on this breakthrough?

Anderson: Ten years ago, StemCells Inc. called me and said, “We’d like you to test our human stem cells in an animal model.” I told them I don’t do stem cell work, which was a foolish thing to say, really. But they were very insistent. They appeared in my office a few days later and laid out their data. And I said, “Wow, that looks really cool. But I don’t do stem cells.” In the end, they convinced me to do a pilot experiment. And I told them, “There’s really only one person I can trust to help me.”

Cummings: So it was a total fluke. I was chair of the science department at Sage Hill School, and Aileen recruited me to work on her spinal cord injury/stem cell animal model program. That has spun into a huge world of not only clinical trials but discoveries of how inflammation intersects with stem cells. It’s turned into a much bigger thing than either one of us would have imagined.

Why did StemCells Inc. single out your lab for the study?

Anderson: In the course of studying inflammation and spinal cord injury, we’d developed a specialized animal model: immunodeficient mice.

Cummings: If you put a human cell in a mouse, the mouse doesn’t like it. Had this experiment been done in standard lab mice, it probably would have failed, because their immune system would have rejected the human stem cells. This whole experiment would have been lost. But Aileen is an expert in neuroimmunology. It was a whole other level of serendipity.

During the experiment, what was the “Aha!” moment when you realized the treatment worked?

Anderson: We had this very long pilot experiment. We were looking at the motor function in animals with spinal cord injury and asking, “Could stem cells improve their coordination, their ability to step, their balance?” We didn’t know what would happen with these cells.

Cummings:: We also didn’t know if our tools to measure stepping or walking or balance were sensitive enough. So we had to create new methods to measure recovery.

Anderson: When we broke the code four months after the transplant [to see which animals had received the stem cell therapy and whether they experienced improved motor function] and had a statistically meaningful result, we were very excited.

Cummings: We thought, “Holy cow! We got something!” We replicated that experiment three times before we published.

What was your reaction when, based on your findings, StemCells Inc. got the go-ahead to conduct a clinical trial on human patients?

Cummings: StemCells Inc. announced that we were approved for a clinical trial on my birthday. I posted it on my Facebook page and said, “This is the second-proudest day of my life” — the first being the birth of our child. [They have a 6-year-old daughter, Camryn.] Who knew this would actually be tested in people so soon?

Anderson: As researchers, Brian and I are interested in the bridge between basic biology and translational science, with the goal that maybe something we do will help people downstream. To have that come through in such a direct way and to produce work that is the foundation for a clinical trial is pretty cool.

What’s the status of the trial, currently under way at Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich?

Anderson: In December, they completed transplantation in the first three subjects, and now they’re collecting data for six months to see if the treatment is safe. If it all looks good, they’ll move to the next phase this summer. This group will include subjects with incomplete injuries, where the potential to detect efficacy is greater. In other words, are the cells doing good?

The first three patients had no sensory or motor function. They can’t feel anything; they can’t move anything. You would need a big, whopping effect to see any improvement in these subjects. Patients in the next cohorts will have a little bit of sensory or motor function. There will be more areas of spared tissue. We’re counting on that as a path to restore connectivity.

What’s it like to know that your work could have an effect on people with spinal cord injury?

Anderson: About 1.3 million individuals in the U.S. live with paralysis from spinal cord injury. It’s devastating. It impacts their bowel, bladder and sexual function. Many have to have someone help them get up in the morning. That’s crushing for anyone. It’s very tough for patients and their families.

People email me frequently — either folks who have been injured a long time or parents whose child was just injured. They’re a very involved community; they keep a bead on what’s coming down the pike in terms of research.

Cummings: What’s amazing to me is that just 10 years ago, StemCells Inc. was talking to Aileen about transplanting stem cells in animals, and now it’s already in a clinical trial. If you’re sitting in a wheelchair, 10 years is an extremely long time, but it’s short in terms of scientific progress.

Had we not been a team, this never would have happened. If the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation hadn’t supported the spinal cord injury research that brought us to UCI, this never would have happened. There’s a lot of serendipity. It’s how science works.

Originally published in ZotZine Vol. 4, Iss. 7