Mind games

Your brain plays tricks on you, UCI research shows

It doesn’t take a prankster to get suckered on April Fools’ Day. The human brain is perfectly capable of playing tricks on itself, according to University of California, Irvine researchers.

In honor of April 1, here are a few reality checks for your mind’s powers of perception and memory:

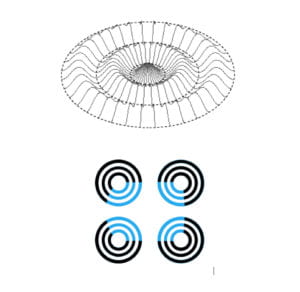

Seeing is deceivingIn the first example, nicknamed “The Ripple,” it’s all but impossible to view the image as flat, even though it is, of course, two-dimensional, says UCI cognitive scientist Don Hoffman.

In the second illustration, people typically see a blue, rectangle-like shape in the center, overlapping part of the circles. In truth, the only blue is in the circles’ arcs. Any color beyond that “is entirely constructed by your visual system,” Hoffman says. “To check this, you can cover up the arcs, and you will see the blue disappear from the interior area.”

The lesson from such images, he adds, is the deceptive nature of eyesight. Many people mistakenly believe the human eye records reality like a camera, he says, but everything we think we see – color, shading, texture, motion, shape and entire visual scenes – is actually fashioned inside the mind.

More optical illusions can be found on Hoffman’s website and in his book Visual Intelligence, which is sprinkled with so many illustrations that it “can be thoroughly enjoyed both right side up and upside down,” one reviewer quipped.

Eyes vs. ears

Depending on which face you watch, you’ll hear either “pa” or “ta.” Close your eyes and you’ll detect just one sound: “pa.” What’s going on? It’s a phenomenon called the McGurk Effect, in which the mind combines what it hears (in this case, the word “pa”) with what it sees (the face on the right is silently mouthing “ka”) and ends up perceiving a sound that doesn’t match either sensory input (“ta”).

Gregory Hickok, a professor of cognitive sciences, explains that the brain processes sights and sounds together, not separately, in an attempt to “build the best hypothesis” about incoming sensory stimuli.

UCI researchers are mapping brain circuits to understand how, where and when visual and auditory information combines. The studies could help people who suffer hearing loss (and use lipreading to aid perception) or lose their language abilities after a stroke, Hickok says.

Malleable memories

Memory is another questionable barometer of reality. Just ask anchorman Brian Williams or presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. But celebrity brains aren’t the only ones that embellish the past. Lots of people recall earning better grades, giving more to charity and seeing their children first walk and talk at younger ages than actually was the case, says Elizabeth Loftus, a renowned memory expert and UCI professor of social ecology, law and cognitive sciences.

Such prestige-enhancing “spontaneous memory distortions” are just one example of the brain’s unreliable recordkeeping, she notes. In various experiments, she has also demonstrated that memories can be altered – or even created out of thin air – by things people are told. The findings have caused a stir in the legal field, and Loftus is now a sought-after commentator, expert witness and consultant on high-profile court cases.