UCI Podcast: At the intersection of economics and political philosophy

Professor Aaron James talks about debt, dollars and how the U.S. monetary system can work for everyone

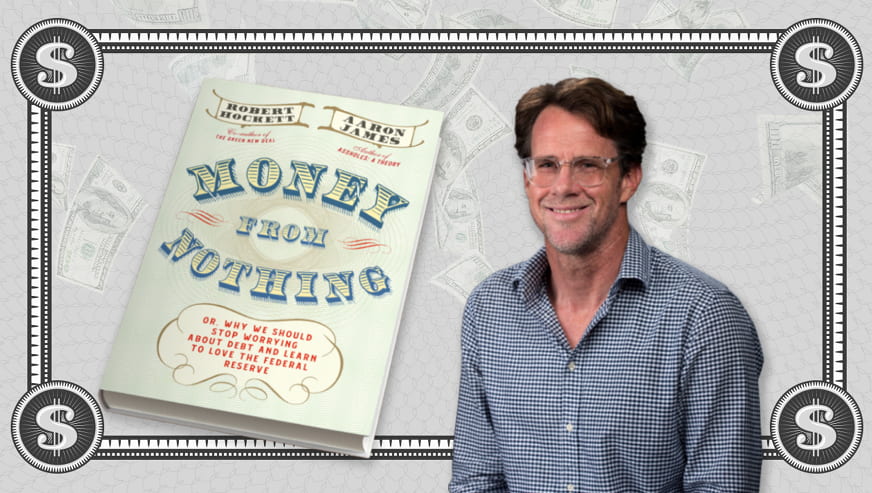

What is the Federal Reserve? What does it do? When is debt not a bad thing? Is a universal basic income economically sustainable? Why would you take financial advice from philosopher? Aaron James, UCI professor of philosophy, works at the intersection of economics and political philosophy and is co-author of a new book, “Money from Nothing: Or, Why We Should Stop Worrying About Debt and Learn to Love the Federal Reserve,” published by Melville House. He answers those questions and more in this conversation with UCI Podcast.

To get the latest episodes of the UCI Podcast delivered automatically, subscribe at:

Apple Podcasts – Google Podcasts – Stitcher – Spotify

Transcript

Hi, I’m Pat Harriman and this is the UCI Podcast.

Joining me today is Aaron James, philosophy professor at UCI. We’re going to talk about the U.S. monetary system, universal basic income and building an economy that works for everyone without unwanted taxes and added regulations.

You may be wondering why you would take financial advice from a philosopher, but Professor James works at the intersection of economics and political philosophy. He teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on the philosophy of money and is co-author, along with Robert Hockett, of a new book called, “Money from Nothing: Or, Why We Should Stop Worrying About Debt and Learn to Love the Federal Reserve,” published by Melville House. Hockett helped draft Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal and has also worked at the International Monetary Fund and The Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Professor James, thank you for joining the UCI podcast.

Thanks a lot. Great to be with you.

Let’s talk first about your book title. There’s so much there to unpack and I think that will help us launch into deeper questions. What exactly is the Federal Reserve, what does it do and why should we love it?

The Federal Reserve, “The Fed” as we call it, is of course, our central bank. It’s a public bank. It was established in 1913, and we, when we in effect “socialized” the dollar, in creating a public-private bank partnership that never existed before that became the backbone of American capitalism. So, the Fed issues the U.S. dollar, which is a kind of government promise. And if you look at a dollar bill, by the way, it says Federal Reserve Note right along the top, so that’s a note; it’s legalese for promissory note, so it says it’s a promise. And what it is in effect is a tax credit for us, which we can use to pay taxes or other debts to the government and, at the same time, a debt of the government to us to recognize those credits.

So, okay, should we love the Fed? Why care about it? Well, think of it this way, do you like dollars? Do you want more dollars? Are you perhaps organizing a lot of your life around getting your hands on more and more dollars? Well then, you like public debt. A dollar just is a government debt, issued by the Fed. If there were no such debt, no one would have any money at all in dollars. So we already in effect already love the Federal Reserve already; we just don’t realize that’s what we love.

So much of our common financial literacy is around preventing and getting out of debt, yet, in your book title, you say we should stop worrying about debt. Why is that?

Uh yeah. Well, we’re taught to, and rightly, worry about our personal debt or private debt; you know, the debt of a company or a state like California. That’s, in that case, you know, you’re worrying about your income, not meeting your debt obligations, and risk of going broke. But the situation is really different, um, when we’re talking about public debt. It’s special, and we aren’t taught to really understand how it works. I mean, take this as an example. Like the “national debt” figures, which you see posted on billboards in various cities, you know, or online. You know, there’s this giant, really long big number, and it’s flying upwards and that’s supposed to be really scary, alarming. You’re supposed to think the debt’s out of control and stuff like that. How are we going to pay back that money, etcetera? But now, think about this point of accounting.

That number is exactly equivalent to private national wealth. That is to say, the public debt just is private wealth, excluding the foreign sector. So think about that. Why? Because every dollar that’s, or every dollar denominated debt, that’s the debt of the government, is an asset to someone else. It’s a dollar in your pocket, or a treasury bond or some other kind of. It’s somebody else’s asset, somebody else’s wealth. Now, once you note that point of accounting, look again at the sign, at that giant number. That’s the amount of private wealth in the national economy. That’s our national private assets. So we’re rich! The number’s flying upward!

Well, but what about all that public debt “being left for the grandkids, then?” Well, that’s all private wealth, the national assets. The grandkids are going to be rich as they inherit all that money. If we were to pay it down, because we’re worried about there being too much of it, well, we’d have to take that wealth away from them. And why should that be a good idea? Yes, so of course leave it for the grandkids. And note, by the way, that that is just a point of accounting, of national accounting. It’s not controversial, or it shouldn’t be controversial. The fact that it is seems a point of controversy just reflects the fact that so many of us, even sophisticated people, just are fairly ignorant of basic facts about money and public accounting.

Well, the thing that people often worry about debt issued by the Treasury, which I mentioned Treasury Securities. What’s going on there is that the government is getting dollars back from the banking system, temporarily, pulling them out of the economy. And it’s promising to re-issue those dollars, really new dollars, with a little extra, an interest rate attached at a certain period of time. But should we worry there about not being able to pay back those monies? Well we shouldn’t, because the U.S. pays people back in its own money, dollars, which it just simply creates at will. It creates those dollar promises just in the way that you and I create promises about our future whereabouts. We have the authority to do that; the Federal Reserve has the authority to create dollar promises and create them from nothing in just that way.

And so there’s no risk of not being able to pay back those debts for the government, because it just always issues new dollars to meet the debt obligation, including any interest payments. So we can’t “go broke” as it were, involuntarily. And anyway the U.S., partly because of its distinctive situation, doesn’t have to “borrow” in that way at all. If we wanted to, we could shift all the government liabilities that are on the Treasury balance sheet, all that Treasure debt, and just move it over onto the Fed balance sheet, the Federal Reserve balance sheet, where they’d be no interest payments due.

That’s basically the same thing from the government’s point of view, because from the government ‘s point of view, it just has a consolidated balance sheet of all these many different balance sheets. They sort of net out to be the same thing from the government’s perspective, but there’s no interest when their liabilities are booked on the Fed balance sheet versus the Treasury balance sheet. So it’s just like having money in one account versus another account, except on one of the accounts, the Fed account, there’s no interest payment; no interest obligation. Well then you might ask, well why are we so silly as to issue Treasuries at all? Well, for sort of technical reasons, but it’s not to “raise funds” to pay for stuff. It’s other reasons. For example, to create a safe asset for investors. So, you know, it’s more “socialism” so to speak, this time for capitalists. Or you know, retirees and pension funds and stuff like that.

So the idea of a universal basic income no longer seems impossible in the context of COVID-19 and is, in fact, gaining bipartisan support. We’ve seen stimulus payments, rent relief and additional programs geared at putting money in the pockets of Americans during this tumultuous time. Beyond addressing the immediate crisis, how would a universal basic income be economically sustainable?

Right. So think about those $1200 checks or bank credits that we just received as stimulus payments. Where did that money come from? Well, the answer is: The Congress just decided it should exist and the Treasury coordinated with the Fed just to create it out of thin air, mainly by typing money into bank accounts, with computer keystrokes. Those are just government promises that it just issued from nothing, the way that you or I issue promises about our whereabouts. You can do that if you have the right authority, just by deciding to do it.

Now, that was really necessary during the Covid emergency. But you might say, “Not only is that emergency not over, we’re in a larger emergency about democracy, climate change, and they require us to do similar kinds of things. And we can, in fact, keep giving people money, formed nothing, from nothing, in the same way, indefinitely. We can do that as long as there’s not a problem with unhealthy inflation – “there’s too much money chasing too few goods.” At the moment we’re struggling against deflation – there’s not enough money out there chasing goods and services. And of course millions of people are not only unemployed, they’ve seen nearly 50 years of stagnating wages when they do work. That’s a break in our social contract, as it were. How do we make good on our social contract over the longer haul? Well, it’s as easy a just giving people money and guarding against unhealthy inflation.

In your book, you say that the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank can create money “out of thin air.” How would that affect inflation, deficits and/or foreign exchange rates?

Right. So inflation is really the key thing here. Even when there’s no sign of it, like there isn’t right now, except in the stock market and certain real estate assets, but across the economy overall, there’s no sign of inflation. But still, people, if there’s any hint of it, or any thought of issuing money, people start yelling about hyper-inflation is just around the corner – Zimbabwe, Weimar Germany – so there’s a lot of scaremongering, fearmongering that goes on around this topic. That’s exactly the kind of thing that our book hopes to expose for its silliness, just by giving us a way of understanding what’s going on to see through its silliness. So, money isn’t scarce, we can create as much of it as we need to service important social purposes, whether that’s supplementing people’s incomes, clean technology investment for climate change, securing full employment. Things like that, as long as we hold inflation to a healthy level. But what people don’t appreciate is that the Fed has plenty of tools – both existing and those we could easily allow it to use – to guarantee that inflation won’t ever become a problem. So we can guarantee that we can hold inflation. We’re not, we can protect ourselves against hyperinflation, so there’s no reason to be really afraid of it.

So we outline in the book a bunch of those tools. The most exiting one, just to mention one of them, is for all of us to have an account at the central bank, in the way that private banks already do. So the Fed would then credit our accounts, with say, $2,000 a month as a basic income payment, and then crucially, it would attach a rate of interest to that, which it would adjust up or down to get us to save or spend. So it looks at the data coming in and sees that prices are rising too quickly, it starts to worry about inflation. Then the Fed can just raise the interest rate on our accounts, giving us more of an incentive to save our money instead of spend it on stuff. And then the idea would bring inflation under control, and if not, it can do other things. And by the way, that’s exactly what the Fed already does with the big banks, with the accounts that they have with it. So we’re suggesting it could do the same thing, sort of democratically, and far more efficiently, if it did it with all of us, banking with all of us. We’d have a more efficient monetary system, a more productive economy, and we’d all be better off – especially the worst off among us, who’d have sure money, the basic income payment appearing in the bank.

So it might seem unusual at first for a philosopher and an expert in financial regulation to team up and write a book on the U.S. monetary system. But it’s not unusual given your background. Why don’t you tell us a bit about your background and how you and Robert Hockett connected to write this book.

I’ve been working at the intersection of political philosophy and economics for a long time, especially on the topic of fairness in the global economy. Bob and I became fast friends when we were collaborating around a documentary that’s based on a different book that I wrote, that’s called, Assholes: A Theory. Bob and I realized we’re on the same page across a whole range of topics, so we decided to write a book for a general audience that pulls all the strands of law, economics, philosophy together in a way that you can’t really do, at least not in a readable, accessible way, within the confines of a book for an academic audience. And plus, the ideas, well look, this is a democracy, or supposed to be a democracy, right? So shouldn’t everyone really understand how our monetary system works and how it might all work better for us? And so we felt like it should be available to the general educated reader, so we could all sort of get a handle on it.

So what would you tell students who are interested in studying philosophy as a means of effecting societal change?

Well, I don’t know. I suppose, don’t get your hopes up too high, but philosophy does give you an essential set of tools, and after all, well such as being able to think clearly and identify assumptions that people don’t realize they’re making. And even just understanding things deeply and seeing new possibilities helps society with “the art of the possible” as it were. And in the big big scheme of things, you know, ideas make a huge difference over time, on, you know, how society is shaped and what kinds of things we do, for better and for worse. And so, you know, be able to engage that is, in a way, it’s important in its own right.

So are there any other insights or perspectives on the philosophy of money you’d like to share?

Oh I guess one thing that’s worth mentioning that sort of surprised me was that the topic of money, the more I got into it, I realized that it’s mostly been ignored by philosophy, in much the way it’s been ignored by neo-classical economics, at least in recent decades, or fairly long time. So our books isn’t simply popularizing stuff that academics necessarily know already. I mean, some do, and many don’t. So this turns out to be a really important research area as well. And I’m now writing a bunch of things for philosophers or other academics to help them appreciate how important and exciting the topic is.

Thank you, Professor James. And thank you for listening to the UCI Podcast, which is a production of UCI Strategic Communications & Public Affairs. The theme music is by Jimmy Moreland.