Bridging the first-generation gap

Mentoring program pairs new students with upperclassmen who also are first in their families to go to college

Anita Casavantes Bradford, associate professor of history and Chicano/Latino studies at the University of California, Irvine, likes to show new students pictures of herself graduating from a community college near Vancouver, British Columbia, where she grew up. It’s a proud moment in Casavantes Bradford’s life, and her purpose in sharing it is to let undergraduates who are first in their families to attend college know that, although they may feel out of place, they’re not alone. They can succeed at a competitive university. They’ve got this.

“I speak as the first woman in my family to finish high school,” says Casavantes Bradford, who went on to earn a doctorate in U.S. and Latino/Latin American history at UC San Diego but never forgot those awkward early days of college. “Back then, I didn’t know about other first-generation students. All I knew was that I was the daughter of a single, welfare-dependent mother, and we had no money, and all of these kids had parents who were professors, doctors and accountants. I’d only seen those kind of people on TV.

“If there had been some kind of group for students like me – oh, what a weight that would have taken off my shoulders.”

Her desire to ensure that UCI students don’t feel as isolated as she once did prompted her to instigate a new mentorship program, the First Generation First Quarter Challenge, which will pair freshmen and transfer students with third- and fourth-year undergraduates and faculty whose parents also did not earn a college degree. (Watch videos of first-generation UCI students.)

Launched this fall by the School of Social Sciences and the Division of Undergraduate Education’s Student Support Services, the program is part of a new First Generation Faculty Initiative that Casavantes Bradford helped establish (see related UC Newsroom story).

“We want to ease the transition for incoming students,” she says. “Some of them struggle through the first year with the feeling that they don’t belong here, that they’re inadequate. They imagine that everyone else is a second- or third-generation student.”

The reality is that nearly 60 percent of UCI undergraduates are first-generation, Casavantes Bradford notes. They don’t have the benefit of parents or extended family members who can advise them on everything from good study habits to stress management. They haven’t spent their lives moving toward the day they’d contend with challenging syllabi and demanding reading lists.

“They haven’t had 18 years of orientation toward college,” she says.

The First Generation First Quarter Challenge will accept new social sciences students in fall 2016. (Casavantes Bradford hopes that other schools will adopt the program as well.) This year, a select group of first-generation undergraduates are training to become mentors and helping faculty and staff shape the program.

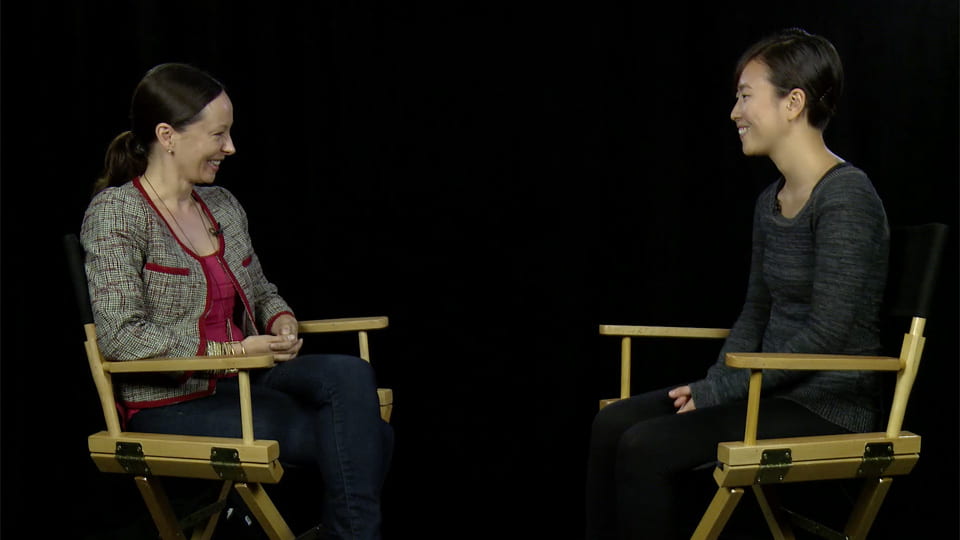

“Who knows what first-generation students need better than the ones who have already been there?” says fourth-year student Ester Kim, who signed on as a mentor. The daughter of South Korean parents, she was born and raised in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and transferred from Cypress College to UCI in the summer of 2014 to pursue bachelor’s degrees in psychology & social behavior and criminology, law & society.

“Coming from a sheltered background to a university environment was culture shock. I didn’t know where I fit in or all of the opportunities here at UCI,” she says. “I felt really left out.”

A mentor in the School of Social Ecology’s Access program helped Kim acclimate, introducing her to research and networking associations where she made friends. “Now I want to help other first-generation students feel a little more at ease,” she says. “Social support is really important for them.”

Kim and her fellow mentors will lead weekly group sessions and meet one-on-one with students, encouraging them to adopt practices that will help them get the most out of college, among them time management, note taking and connecting with professors.

Participants will be assigned tasks, such as summoning the courage to visit professors during office hours or sitting in the first row of a lecture hall and asking questions in class.

These activities are intended to improve first-generation students’ academic performance. Their GPAs lag behind those of their peers by about a third of a letter grade, Casavantes Bradford notes, and that’s often due to a rocky first quarter.

“They already fear they don’t belong here, and now they have to drag this albatross of their first-quarter GPA around with them,” she says.

Even a slightly lower GPA can make a big difference in their lives, determining whether they’ll get into graduate school, win scholarships, land the best internships and gain other advantages.

“We have a lot of students who hover at a 2.9 GPA. They haven’t broken through 3.0, which is fundamental to their future success. We want to help them close the GPA gap,” Casavantes Bradford says. Participants’ academic performance will be tracked to gauge the First Generation First Quarter Challenge’s effectiveness.

She hopes that the mentoring program and the faculty initiative will also foster a well-deserved sense of pride among these pioneering students. Someday, they might even show their graduation photos to a classroom full of excited, nervous newcomers.

“We’re creating a community, an identity,” Casavantes Bradford says. “UCI is a first-generation campus and a top research university. It’s not either/or – and that’s something we should celebrate.”