A labor of love

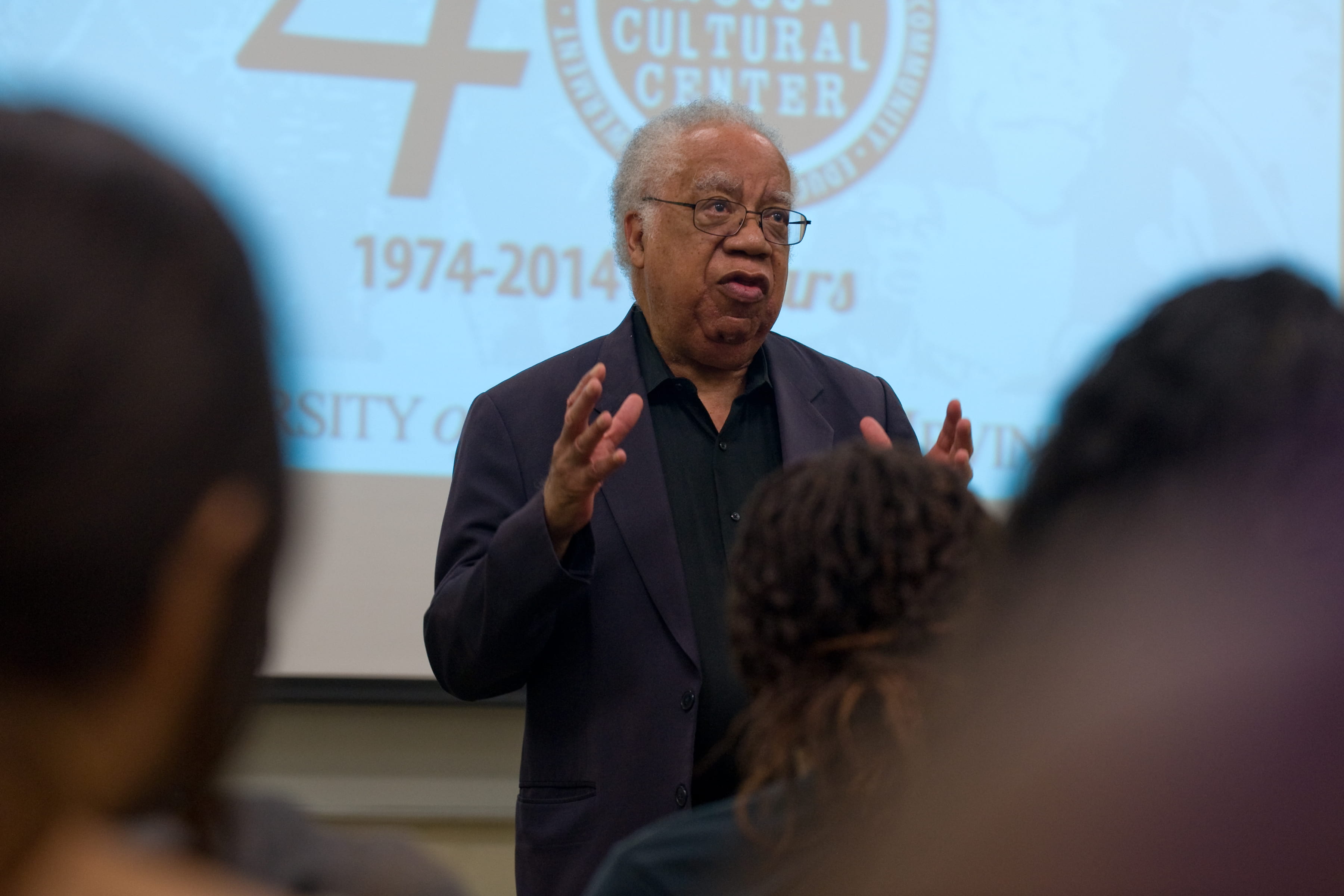

Joseph L. White, ‘father of black psychology,’ is honored by American Psychological Association

Joseph L. White, professor emeritus, joined the University of California, Irvine about four years too late to be a founding faculty member. But what he lacked in years, he made up for in scholarship and attitude.

He came to UCI in 1969 as a professor of social sciences and bucked academic tradition in the field of psychology from the start. As a result, the man who became known as the “father of black psychology” produced a body of work that was lauded in August at the American Psychological Association convention in Toronto during what the organization called “Joseph L. White Day.”

“Your numerous books and articles and your seminal manuscript ‘Toward a Black Psychology,’ published by Ebony magazine in 1970, were instrumental in beginning the modern era of African American psychology,” the APA citation reads. “It is of little wonder that you are honored and respected by all those who have been fortunate to have had the opportunity to interact with you. … Psychology is significantly enriched by your insightful leadership and extraordinary career.”

With the approach of Labor Day and UCI’s 50th anniversary, White talks about how a young academic at a new university discovered his passion and embarked on a lifelong labor of love.

How did you identify “Toward a Black Psychology” as your life’s work?

I got my doctorate in 1961 in clinical psychology from Michigan State University, and I was one of just a few black Americans to achieve that from an American university. I read the psychology literature, and two things became apparent to me: First, we as black people were invisible. I read all the books, and we were not there. We were absent in psychology. Where we did appear in the literature was in deficit-deficiency models – we had low IQ, couldn’t do complex tasks, and in two World Wars the U.S. Congress determined we could not be trained to fly airplanes. Well, I knew I existed. I came from a one-parent home where my mom raised three kids, clothed and fed us and got us through high school and kept us out of trouble, and that’s a complex task. So I challenged the board of directors of the American Psychological Association. And then in 1968, nine more of us challenged them. It was a knock-down-drag-out. They said it’s easy to criticize and say what you don’t believe in, but what do you believe? Ebony magazine asked me to start the conversation about black psychology. So I wrote it up, and in September 1970 a million copies of the magazine reached more than 2 million readers. Everyone and their mamas had something to say. Some criticized me for bringing race into psychology, and some liked it, and suddenly I was a very popular young man.

Was there anything in particular about UCI that allowed you to pursue this labor of love?

Looking back now, UCI was so new that ideas about how things should be done weren’t settled in place. I got to do things before people realized I was doing it. At a more established university, I would have run into the psychology bureaucracy that said Ebony wasn’t a scholarly publication, and we shouldn’t be popularizing psychology, that I shouldn’t bring race into psychology and that I was too confrontational. Well, today a big section of bookstores is popularized psychology. Bringing race into it started discussions with Asians, Native Americans and Mexican Americans and opened the door to ethnic psychology studies. And we were confrontational; those weren’t nice meetings with the board of directors of APA.

I know many people consider you a mentor. What role do you believe our mentors play in helping us achieve our goals?

I’m from a black, one-parent, low-income home, and I knew there were kids out there with the same background that had ability, whereas people who were supposed to be responsible didn’t know what black grad students were about. I felt it was my job to help them develop the self-confidence to succeed. The ability was there. I took them to conventions, meetings, stuff like that, to meet other people. That’s how they got hands-on experience.

What advice would you give to students today who are looking to discover their calling?

I would say to try to find a role model that represents what you want to be. It doesn’t have to be a clinical psychologist. It could be a lawyer, a doctor or MBA. Just find someone you look up to. There must be something in a big university that can light a fire inside you. That fire provides the motivation for you to climb the mountain.