Grad students get leg up from Google

Two in ICS’s doctoral program win fellowships recognizing world’s ‘most promising young academics’

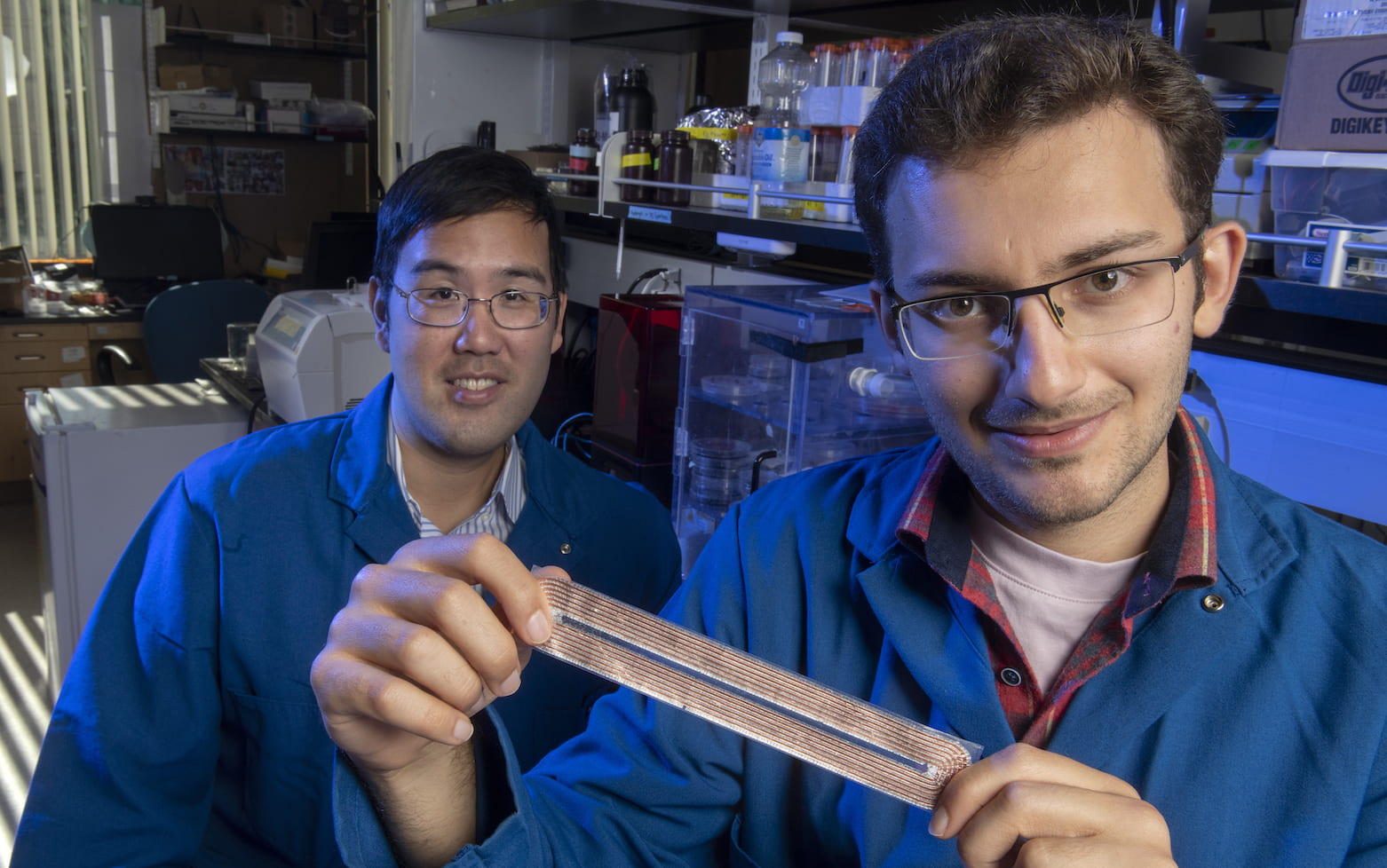

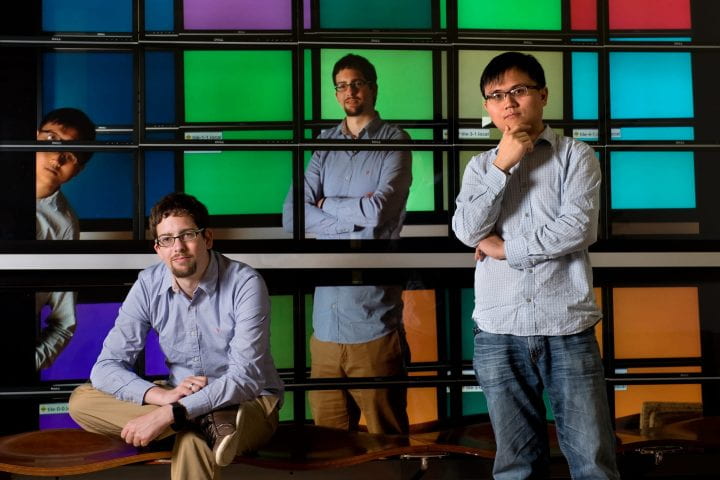

One aims to streamline big data, making it faster and easier for companies to share. The other wants to guard folks’ personal information online. Both are doctoral students at UC Irvine’s Donald Bren School of Information & Computer Sciences and recipients of 2013 Google Ph.D. Fellowships.

Yingyi Bu and Bart Knijnenburg will have all their University of California fees paid and receive $33,000 each for research for two years running. They have also been assigned mentors at the Internet giant, which says on its website that “nurturing and maintaining strong relations with the academic community is a top priority at Google. … This year we awarded 15 unique fellowships to some amazing students in the U.S. and Canada.”

Competition for the prestigious grants is tough, and ICS Dean Hal Stern is thrilled that both of the school’s candidates were selected by a company that has traditionally named winners from such well-known institutions as UC Berkeley and Stanford University.

“This was not at all expected. I was obviously hoping at least one would win, but I didn’t expect two,” Stern says. “I’m very excited because we believe that we’re one of the top computing programs in the country, and this is a nice reinforcement of that.”

He notes that the funding will also help the school expand its graduate support in tough budgetary times by freeing up public money for other students. “These awards are powerful in terms of both their recognition and their financial impact,” Stern says.

Bu and Knijnenburg share his joy.

“Oh, I feel excited, because this means that UCI is doing world-class things,” says Bu, 31, a native of China who has been studying computer science on campus for three years. His fellowship project involves designing more efficient computing structures.

“It’s a good opportunity to have a close connection with a Google researcher,” he says. “It’s also an opportunity for me to make the system we’re building have more impact in the real world.”

Knijnenburg, 29, says of the fellowship: “My doctoral adviser told me not to expect to get it because they always give it to the ‘big’ schools. When I got the email saying I’d won, I was really surprised.”

Asked by Google not to publicly share the news for a month, he did go out and celebrate with a few friends.

Keeping such interactions private is at the heart of Knijnenburg’s work, which focuses on informatics, or the relation of humans to computers. Specifically, he wants users’ data automatically kept more private if their online activity seems to indicate that’s what they would prefer.

“My topic for Google is to help people make privacy decisions in varying ways,” Knijnenburg says. “Some people are very private; some people are not. The obvious solution is to give people more control.”

That’s easier said than done, he admits, with the proliferation of online cookies that track usage for companies and even government agencies. Knijnenburg believes that rather than individual consumers trying to figure out how to opt out of complicated data gathering systems, it could be done for them if their habits show that’s what they’d want.

“I, better than anyone, know I should protect my bank account information online, and I know how to do it too,” he says. “But it’s just too complex. And it shouldn’t be. I also at times don’t feel like deciding whether to try to encrypt something. So I choose immediate gratification over the risk of giving away personal information. I’m only human.”

Knijnenburg, who’s also been at UC Irvine for three years, has already patented a method to determine how people make privacy decisions, and he thinks it could be put to good use automating the often overwhelming controls of social networks.

On the surface, Bu’s focus appears to be just the opposite: He’s building new architecture by which the estimated 8 billion Web pages now in existence could be checked against each other more rapidly for ingesting, storing, managing, indexing, querying, and analyzing trends and other information.

As computers have grown increasingly adept at automatically compiling data, it has become unwieldy and time-consuming to sort all the terabytes. Bu is researching ways to better “stack” huge piles of software so that programs can operate together with greater efficiency.

“My primary area of interest is large-scale data management systems, especially data-intensive computing systems,” he says. One current project is Pregelix, an open-source implementation of a “bulk-synchronous” programming model for extensive graph analytics.

Bu points out that Knijnenburg’s work could be aided by his own efforts.

“His privacy protection techniques could probably be much faster with our system,” he says. “He also needs to deal with mountains of data. He could let these algorithms run on ‘share-nothing’ machines.”