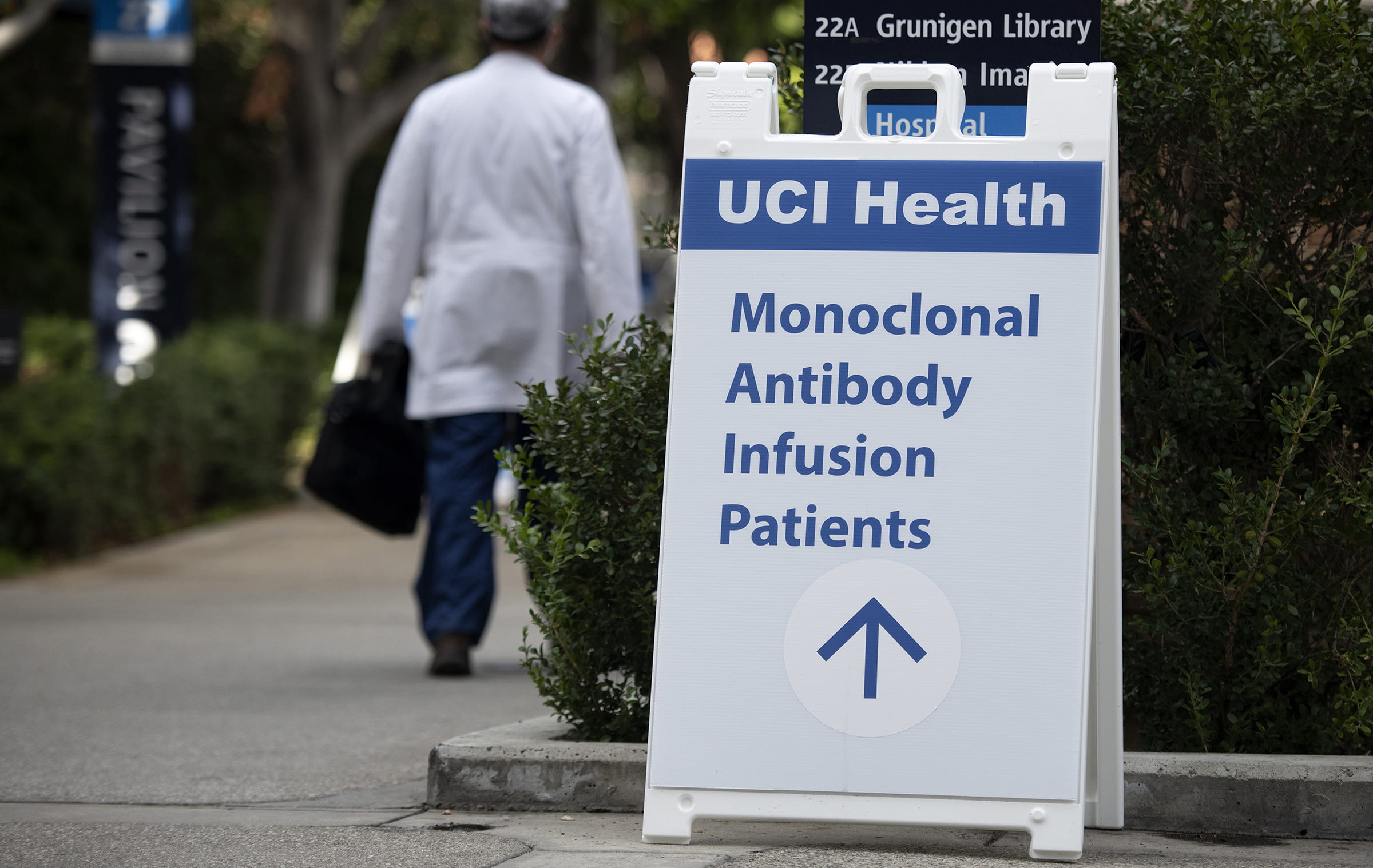

Federal COVID-19 response taps UCI Health as a model for delivering monoclonal antibody therapy

UCI Health treatment method to be shared with healthcare systems nationwide

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 9, 2021 — Monoclonal antibodies are showing promise for improving outcomes for COVID-19 patients, but when a hospital is already beyond capacity, administering them can be a challenge. As hospitalizations soared across California, clinicians with UCI Health created a system for delivering monoclonal antibodies that is keeping hospital beds available for patients with the greatest need.

“The hospital bed is one of the most valuable resources that we have, which has been stretched thin by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Daniel S. Chow, an assistant professor in residence in radiological sciences and co-director for the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Medicine as well as the project’s co-principal investigator. “Every effort to expand the number of beds available counts, and that includes being proactive about preventing hospitalizations.”

They are partnering with the federal government’s response to COVID-19 to share their success in delivering monoclonal antibodies with healthcare systems across the country.

Despite the increasing availability of COVID-19 vaccines, there is still a critical need to identify, develop and expand the use of therapies for those who have the disease. The FDA provided emergency use authorization for the Eli Lilly and Regeneron monoclonal antibodies in November. The treatment – which uses laboratory-made proteins to block the virus from entering into human cells – is authorized for mild to moderate COVID-19 cases in adults and certain pediatric patients who are at high risk to develop severe symptoms or who may require hospitalization.

However, according to NPR and other news sources, healthcare systems have been slow to adopt this treatment because of the steps involved in administering it. The therapy requires an infusion that takes one hour, followed by an hour of observation before patients are released to self-monitor at home.

As of early February, UCI Health had treated about 170 patients with monoclonal antibody therapy and significantly prevented hospitalizations resulting from severe cases of COVID-19.

“As hospitals across the country reach and exceed their ability to accommodate patients due to COVID-19, it is critical that we use every resource to reduce the burden on the healthcare system,” said Col. Brian Burk, program manager for the federal government’s COVID-19 therapeutics response. “When monoclonal therapies are administered appropriately, they have the potential to reduce disease progression and the need for hospitalization, so we are very excited to see success stories like UCI’s.”

Since the therapy is only given to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19, the set-up has to be separated from other patients to avoid spreading the disease. With hospitals at or near full capacity, allocating healthcare workers and a safe, designated infusion space is a challenge.

UCI Health has created a successful system for doing this. They set aside six chairs with dedicated staff in an infusion clinic that allows patients to come in and out of a closed loop system that avoids putting non-COVID patients at risk. Patients who fit the emergency use authorization guidelines are referred to the clinic through their doctors when they test positive for COVID-19. The clinic is capable of infusing 24 to 36 patients with monoclonal antibodies per day.

Using AI technology to aid treatments

UCI is also investigating whether its existing machine-learning tool – which is designed to predict the probability that a COVID-19 patient is likely to need a ventilator or ICU bed – can also identify patients who may benefit from monoclonal antibody treatment. The researchers are incorporating EUA guidelines into the model.

“In combination with EUA recommendations, our tool may help us stratify and identify additional patients who may benefit from monoclonal antibodies,” Chow said.

Of the first 86 patients who received monoclonal antibody therapy at UCI – which included Latino, white, Asian-American and Black patients – only about 3 percent afterward had to be admitted to the emergency department. This tracks with the FDA’s findings that only about 3 percent of high-risk patients treated with the therapy required hospitalization or emergency department visits, compared with 9 percent of patients in the control group.

“If we can avoid ambulatory patients that are symptomatic and COVID-positive from ever having to touch our emergency department or our hospital setting, that helps the community and manages bed flow,” said Dr. Alpesh N. Amin, the Thomas & Mary Cesario Chair of Medicine and the project’s principal investigator.

“The average hospitalization for a COVID patient at UCI is a little over seven days,” added Chow. “So this is actually a very big impact, especially when you consider the associated needs for every hospital day, including nursing and staff needs at a time when personnel are stretched thin, as well as associated medical supplies, etc.”

Using the federal response’s distribution network, UCI Health is sharing their monoclonal antibody delivery system with other healthcare systems. Interested hospitals can reach out to Amin for a consultation.

“Vaccines give us all hope that end of the pandemic is near, but monoclonal antibodies give us ‘more than hope’ because we can now treat high-risk patients with COVID-19 and decrease their risk of becoming hospitalized,” said Col. Deydre Teyhen, deputy program manager for the federal government’s therapeutics response.