Mission to Mexico

UCI staff member Bernadette Strobel-Lopez makes weekly trek to bring basic necessities to victims of the Mexicali earthquake.

Bernadette Strobel-Lopez was sitting down to an Easter meal with her family when the dining room started to shake. It was April 4, and she was visiting her father’s ranch house in the Imperial Valley, just 30 miles from the epicenter of a 7.2-magnitude earthquake in the Mexican state of Baja California.

“It was jarring,” Strobel-Lopez recalls. “Everything that wasn’t bolted down flew around the room. Dishes were falling and breaking. I felt like a rock in a blender. We were all looking at each other in disbelief.” Family members huddled under an archway until the motion finally stopped. The home had minor damage, but everyone was OK.

“We resumed our meal — but we ate outside,” she says.

The story could have ended with Strobel-Lopez returning to the security and comfort of her home near UC Irvine and job as director of the Bren Events Center and going on with life as usual. But when the ground shifted, so did her priorities. Since then, she has spent most of her free time and every weekend bringing aid to those displaced by the earthquake.

She’s launched her own relief effort, traveling 50-plus miles south of the border over cracked and twisted roads in an SUV loaded to the roof with blankets, water, medicine, toiletries and other necessities. She goes to the places of greatest need — the isolated villages called ejidos outside Mexicali where the quake flattened shanties, swamped homes with mud and ruptured water lines.

“We wanted to find areas off the beaten path because they wouldn’t get as much attention or aid,” says Strobel-Lopez, who distributes the supplies with friends from Mexicali. “In Chimil, one of nine ejidos we’ve adopted, they weren’t getting anything.”

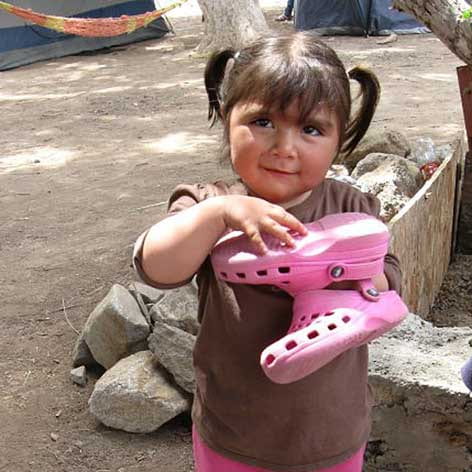

Afraid or unable to go home, lots of Mexican earthquake victims live outdoors, sleeping in tents if they’re lucky. Often, their towns are awash in sludge created by displaced groundwater and septic-tank runoff. Unsafe drinking water and poor sanitation are causing many people to get sick. In one village, 400 residents share a single portable toilet.

While government and aid agencies have provided food to the locals on Strobel-Lopez’s route, they often lack simple goods. She has a long list of needed items: drinking water; mosquito repellent and sunscreen; sunglasses and hats; feminine products; diapers; underwear (for men, women and children); long-sleeved, light-colored shirts (no other clothing); hand wipes; disposable utensils; napkins and paper towels; septic-tank-safe toilet paper; baby formula powder; canned food; rice; and beans. (Donations can be dropped off at the Bren Events Center administrative office.)

“We ask people what they need, and they’ll mention only one thing. They’re embarrassed. They just want the most basic of things that we take for granted every day,” Strobel-Lopez says. “They were poor before the earthquake, and now they have almost nothing.”

With a donation from her father, she’s provided tents for seven homeless families.

“One woman is a single parent with two little girls who are sick. Their house was destroyed,” she says. “Her tent and few possessions were stolen when she went to get a hot meal at a donation center. Another woman is raising her two grandchildren, and they’re living outdoors.”

Strobel-Lopez collects many items from her contacts at UCI, where she’s worked for more than three decades. They’re used to her appeals for help. She’s led relief efforts for victims of Hurricane Katrina and the 2003 wildfires that destroyed homes in San Diego County’s Harbison Canyon.

“People know I get involved in something like this every few years,” she says. “I’ve always liked making sure the stuff goes to those who really need it.”

She spends Friday evenings sorting donations and loading her SUV. On Saturday mornings, she crosses into Mexico, fielding questions from its border agents.

“I speak my best Spanish when someone’s telling me I can’t take things across the border,” Strobel-Lopez says. Her mother is from Mexico, and she’s been visiting the country since she was 5.

Knowing the language also allows her to make friends with the locals and hear their stories.

“I don’t know who’s getting more out of the experience – them or us,” she says. “There’s nothing better than seeing the joy you can bring to people by giving them the simplest items.”