Everyday objects help teach basic biology

Diane O’Dowd uses objects from her garage to demonstrate biology principles and engage students.

Diane O’Dowd remembers sweating the first time she brought the giant cell to class.

She worried that her introductory biology students would sneer at her demonstration, thinking it condescending and grade-schoolish. But when she walked across the larger-than-life cell drawing, acting the part of a motor protein traversing the cell, eyes lit up across the room as students grasped the concept.

A developmental & cell biology professor at UC Irvine, O’Dowd doesn’t sweat over her presentations anymore. Her “garage demos” – so called because that’s where she gets many of her materials – earn rave reviews. She might arrive at class toting tennis balls that stand in for hydrogen ions, or her daughter’s old Halloween wig that doubles as a membrane vesicle studded with spiky purple proteins. In a hurry one day, she grabbed a pair of old soccer socks to represent sister chromatids.

O’Dowd, who’s been teaching for two decades, revamped her lectures to include these garage demos five years ago as her son and daughter approached college age. “Would they like my class?” she wondered. “I concluded that they would not be excited by listening to me lecture, uninterrupted, for 50 minutes.” With funding from the nonprofit Howard Hughes Medical Institute, she began developing and testing educational techniques and teacher-training programs. Among those efforts were her famous demos, hits not only in the classroom but also on YouTube.

When O’Dowd thought back to her own college years at Stanford University, a few courses stood out in her mind. One was introductory physics, in which a bowling ball had been swung on a pendulum to demonstrate principles of friction. So O’Dowd rummaged through her garage and started to build proteins from pipe insulation and membrane phospholipids from PVC pipes, Styrofoam and an old hanger. She recruited her children as testers for new demos before unveiling them in class.

She explains course content with PowerPoint slides and uses the demos to reiterate important concepts. “It puts an exclamation point on the sentence,” says Michael Leon, associate dean of biological sciences.

Also an anatomy & neurobiology professor, O’Dowd found that students can misunderstand key concepts when they’re presented two-dimensionally. For example, many students perceive DNA plasmids as flat circles, which is how they’re typically drawn. But they are actually loops, with empty space in the middle. O’Dowd’s 3-D “plasmid,” manufactured from an old garden hose, illustrates the proper shape.

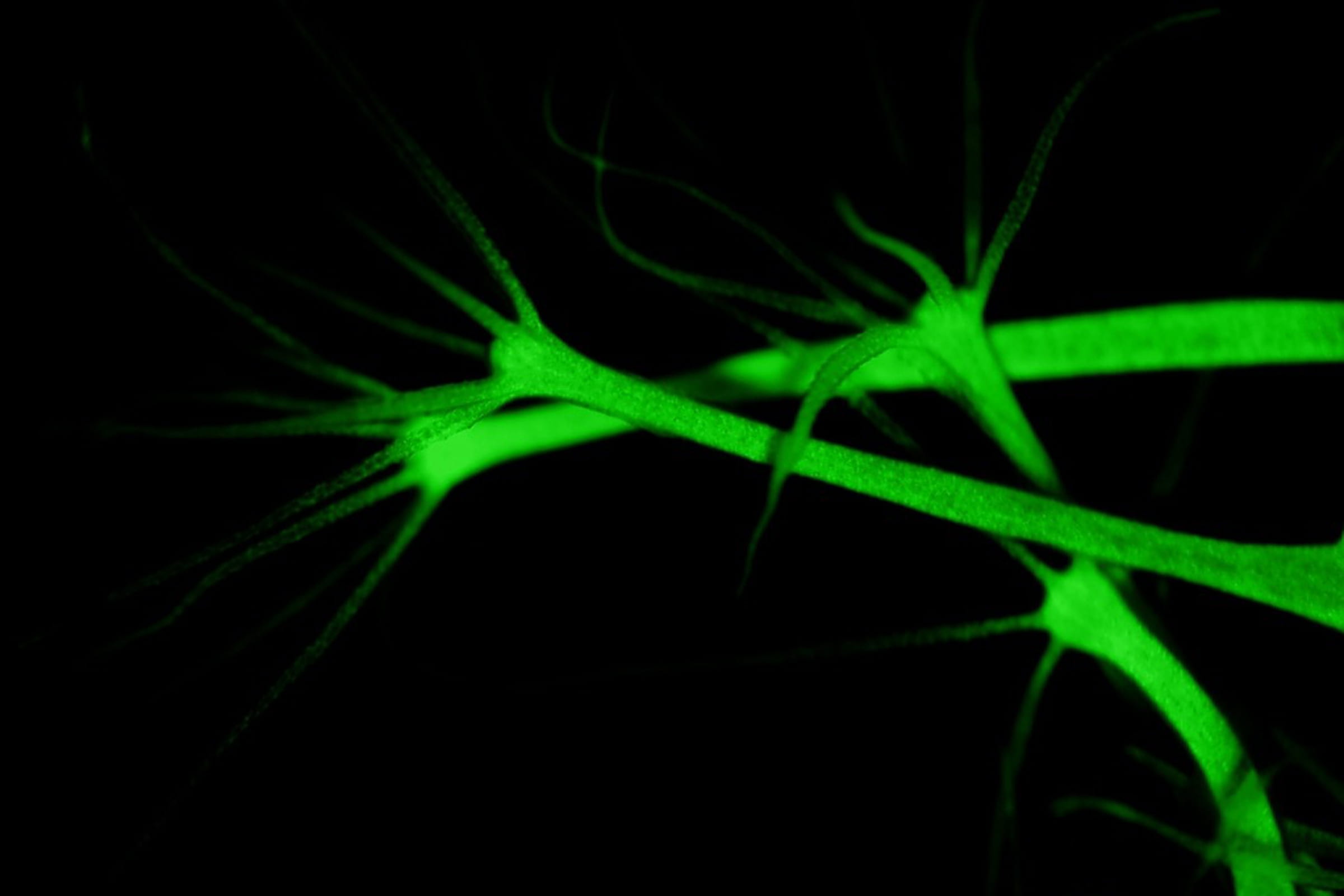

Students often become moving parts in her demos – for instance, they make great motor proteins. A volunteer in O’Dowd’s lecture might portray a kinesin, carrying the vesicle-wig across the giant cell’s microtubule tracks, or one in a lineup of myosins, pulling and pushing to simulate muscle contraction. Dozing off in class is dangerous – the sleepy undergrad could wind up starring as the “resting neuron” in a one-act play on nerve cell stimulation.

O’Dowd tries to break through the invisible barrier between the lecturer droning at the podium and the students slouched in their chairs. “They have to feel like they’re people in your class, not just one in a sea of faces,” she says.

Even those who remain seated are engaged during demos, shouting out instructions to their friends onstage. “They stop looking at their computers and start looking at the lecturer,” says graduate student Melissa Strong, who was a teaching assistant in the course.

In an anonymous survey, 90 percent of students rated the demos “helpful,” O’Dowd reported recently in the journal CBE – Life Sciences Education. UCI sophomore Marina Nemetalla says she thought back to demonstrations during exams and continues to do so now in her research.

The students are not the only ones to benefit. O’Dowd says she gets more satisfaction from teaching than in years past, occasionally even hearing from a student: “You changed my life.”