Speaking the same language

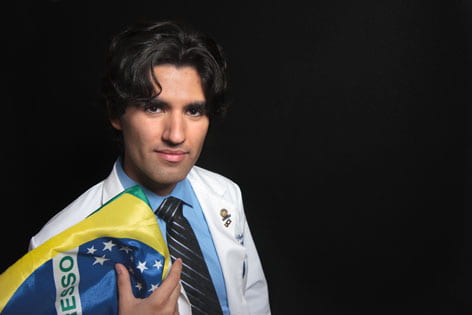

Thiago Halmer and other PRIME-LC students will help doctors in Brazil collaborate with UCI physicians on stuttering cases.

Thiago Halmer knows the isolation that comes from an inability to communicate. At age 6, he and his mother moved from a poor neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro to the U.S.

“I remember sitting in kindergarten crying because I couldn’t speak the language,” he says. “I thought all the other kids were talking about me, and I just felt so frustrated.”

Now a second-year medical student at UC Irvine, Halmer will draw upon his fluency in Portuguese — his native tongue — and English to help people in Brazil overcome a different kind of language barrier.

This summer, he and fellow medical students Craig Harrison, Julio Monterrey and PK Fonsworth will assist Brazilian physicians in treating individuals who stutter. They belong to UCI’s PRIME-LC (Program in Medical Education for the Latino Community), which trains students to meet the healthcare needs of underserved populations, and are working under the guidance of Dr. Gerald Maguire, director of UCI’s Center for the Medical Treatment of Stuttering.

In the coastal city of Porto Alegre, the students will set up a telemedicine satellite center with video monitors at the Brazilian Fluency Institute and teach resident physicians to use technology that enables Maguire and his team can help diagnose and treat patients from afar.

“Many times, when doctors from the U.S. go to help patients in developing countries, they’re there two weeks and then they’re gone,” says Maguire, who spoke at the institute in April. “So I thought, ‘What if we could continue to provide that level of care?’ This project will let us see if we can.

“Brazil has done interesting work on stuttering, and we’d like to exchange information. They view it as we do — as a medical disease that requires neurological treatment.”

Stuttering was once widely regarded as an emotional or neurotic behavior, but Maguire – who stutters himself — and other medical experts now theorize that it begins in the brain. PET scans of people who stutter have revealed a disruption of nerve impulses within the left cerebral hemisphere, which governs speech and motor actions. More research is needed.

With Halmer acting as translator, the UCI students will interview a Sao Paulo boy who has caught Maguire’s attention. His stuttering began with an infection that affected his brain, and it ended when he took antibiotics. The case could yield important clues about the cause and treatment of stuttering.

Maguire will join the group to present their findings on the boy and other patient cases as well as his latest stuttering research at a conference in Rio de Janeiro. The students will then spend three weeks at a local outreach clinic, assisting in the trauma, maternity and other departments.

Halmer has made frequent trips to Latin America to work at health clinics. In addition, he helped Medical Missions for Children set up broadcast channels at hospitals in Bolivia and Brazil so physicians could watch educational programming.

“Every time I go back to my old neighborhood in Brazil, I feel bad,” says Halmer, who lives in a comfortable Irvine apartment, worlds away from his former neighbors’ tiny cinderblock houses. “Here in the U.S., I can accomplish my dreams. But some people I was raised with can never have the opportunities I have.

“Just seeing how these people struggle — how they barely have anything but they’re still happy – makes me want to help. I know the culture, and I can identify with the community.”

Always curious, Halmer decided he wanted to be a doctor at age 12, after being treated for severe appendicitis at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. “I had six specialists, and they all seemed so concerned about me,” he says. “I couldn’t believe they were so interested in my welfare.”

At UCI, Halmer joined PRIME-LC because he liked the program’s service mission. He’s also community affairs liaison for the university’s Latino Medical Student Association, organizing high school workshops to encourage disadvantaged students to become doctors.

“I want to invest my energy where I can do the most good,” Halmer says. “It’s a gift that I can help people through medicine.”