Guarding against toxins

Toxins in food often have a bad, bitter taste that makes people want to spit them out. It’s one way the body defends itself.

Toxins in food often have a bad, bitter taste that makes people want to spit them out. It’s one way the body defends itself.

Now, new UC Irvine research finds that the digestive system provides a second line of defense – keeping bad food in the stomach longer and increasing the chances that it will be expelled.

This defense also triggers production of a hormone that makes people feel full, presumably to keep them from eating more of the toxic food.

The discovery has the potential to help scientists develop better therapies for ailments ranging from cancer to diabetes, and may explain why isolated populations around the world have adapted to eat and enjoy local foods that make outsiders sick.

The study appeared online Oct. 9 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

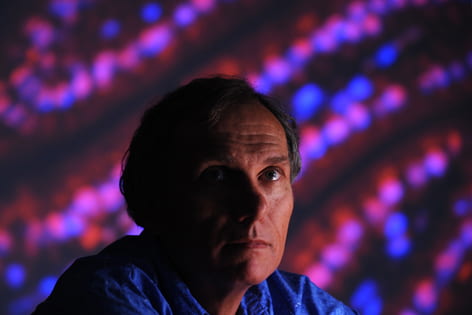

“We have evolved mechanisms to combat the ingestion of toxins in our food,” said Timothy Osborne, molecular biology & biochemistry professor and study senior author. “This provides a framework for an entirely new area of research on how our bodies respond to what is present in our diets.”

Mammals have evolved to dislike the bitter taste of toxins in food. This response is particularly important when they eat a lot of plant material, which tends to contain more bitter-tasting, potentially toxic ingredients than meat.

Examples of bitter-tasting toxins include phenylthiourea, a compound that destroys the thyroid gland, and quinine, found in tonic water, which can be deadly in large doses.

If toxins are swallowed, bitter-taste receptors in the gut sense them and trigger the production of a hormone that both suppresses appetite and slows the movement of food from the stomach to the small intestine.

Scientists say the findings likely explain why groups of people taste certain foods differently.

“One group of people may think something tastes great and can metabolize it just fine, but a group from the outside may think it tastes horrible and get sick,” Osborne said. “The first group likely adapted to the food through a change in the expression and pattern of their dietary sensing molecules.”

With this knowledge, scientists could make medicines less bitter, which in turn would allow for increased palatability and quicker absorption. Drugs used to treat cancer sometimes include molecules that taste bitter. Also, changing the patient’s eating habits could improve the effectiveness of such drugs.

In addition to the appetite-suppressing hormone, bitter-taste receptors in the gut activate the production of glucagon-like peptide 1, a protein that stimulates insulin secretion in the pancreas. Drugs currently are on the market that attempt to stabilize this protein in people with diabetes, and therapies aimed at increased production are attractive therapeutic targets.

“Because bitter-taste receptors are expressed in the gut, a new avenue exists to identify ways to stimulate production of GLP-1,” Osborne said. “It could be very beneficial for the treatment of diabetes and possibly other diseases.”

UCI scientists Tae-Il Jeon, Bing Zhu and Jarrod Larson also worked on this study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health.