Healing with heart

Dr. Marianne Cinat gently restores health and hope to burn victims

It’s everyone’s nightmare. And it’s part of Dr. Marianne Cinat’s daily routine.

Last May, artist Ron Pastucha was preparing for a Laguna Beach exhibition. Taking a break from a series of portraits, he went to the kitchen to deep-fry some tempura. Struck by a moment of artistic inspiration, he padded back to his studio. By the time the absent-minded painter returned to the stove, the pan of oil was on fire. Pastucha quickly grabbed the pan, and the burning oil slopped onto his right hand, which he had just cleaned with paint thinner. His hand ignited.

The injury would have been traumatic for anyone; for Pastucha, it had the power to smash a lifetime of hopes, dreams and efforts. The 42-year-old painter never had any profession but “artist” — a job that depends on the finely nuanced coordination of brush and hand. At the first hospital he entered, the staff told him he would likely lose his thumb. He was quickly moved by ambulance to UCI’s Regional Burn Center.

Enter Dr. Cinat, medical director of the leading-edge burn treatment center. One of the first such centers in the nation, it prides itself on breakthrough technology and treatments — as well as its care.

“For me, caring for patients is what takes priority and what I love. I couldn’t be a doctor if I didn’t do that,” Cinat says.

CRITICAL MOMENTS

She needs her gentle bedside manner to deal with the kinds of patients who routinely enter the center: infants scalded by a moment’s inattention to a hot-water faucet; teenagers who fall into bonfires or fire pits during horseplay; passengers pulled from burning vehicles — all of them threatened with permanent disfigurement.

“What’s special about burn care are its long-term relationships,” Cinat says. “Some of our patients are in the hospital for several months. You develop a very special bond with them and their families.”

Cinat’s caring style revealed itself in Pastucha’s case when she made sure images of his paintings were projected on the operating room walls while the artist underwent treatment — a reminder to the entire surgical team of the artist’s talent and what was at stake.

Why does Cinat get so involved? A big reason is teamwork, she says. “You need a team to take care of patients. It’s not just about healing the wound. It’s about treating the whole patient. Recovery requires physical therapy, occupational therapy, nutrition. You need social workers, psychologists, specialized nursing care. It’s very challenging for everyone.”

Cinat grew up in Southfield, Mich. Her dad was an engineer, her mom a nurse. For that reason, “Working with people, helping people, seemed a very natural thing.” She also loved science, particularly biology.

A career as a doctor beckoned. “I don’t really remember being determined to be anything else,” she says, “other than a singer — but I had no voice.”

Patients are grateful she’s no coloratura. Michael Condiff, retired principal of Brea Junior High School, was helping his son restart his Shelby Cobra race car three years ago when it exploded. Condiff was on fire, and inhaled flames down his throat.

“I missed Christmas, New Year and darn near Valentine’s Day,” Condiff recalls. “I was in a coma for six weeks — an induced coma, so they could treat the burns. As they scrub these burn wounds, there just isn’t a way you could withstand it if you were awake.”

Given an 18-percent chance for survival, he credits Cinat and the burn team for turning those odds around. “She has incredible compassion and commitment toward what she does. You’re not just some guy who got burned. I will value my friendship with her like very few I have had in my life.”

SPECIAL TOOLS, SPECIAL CARE

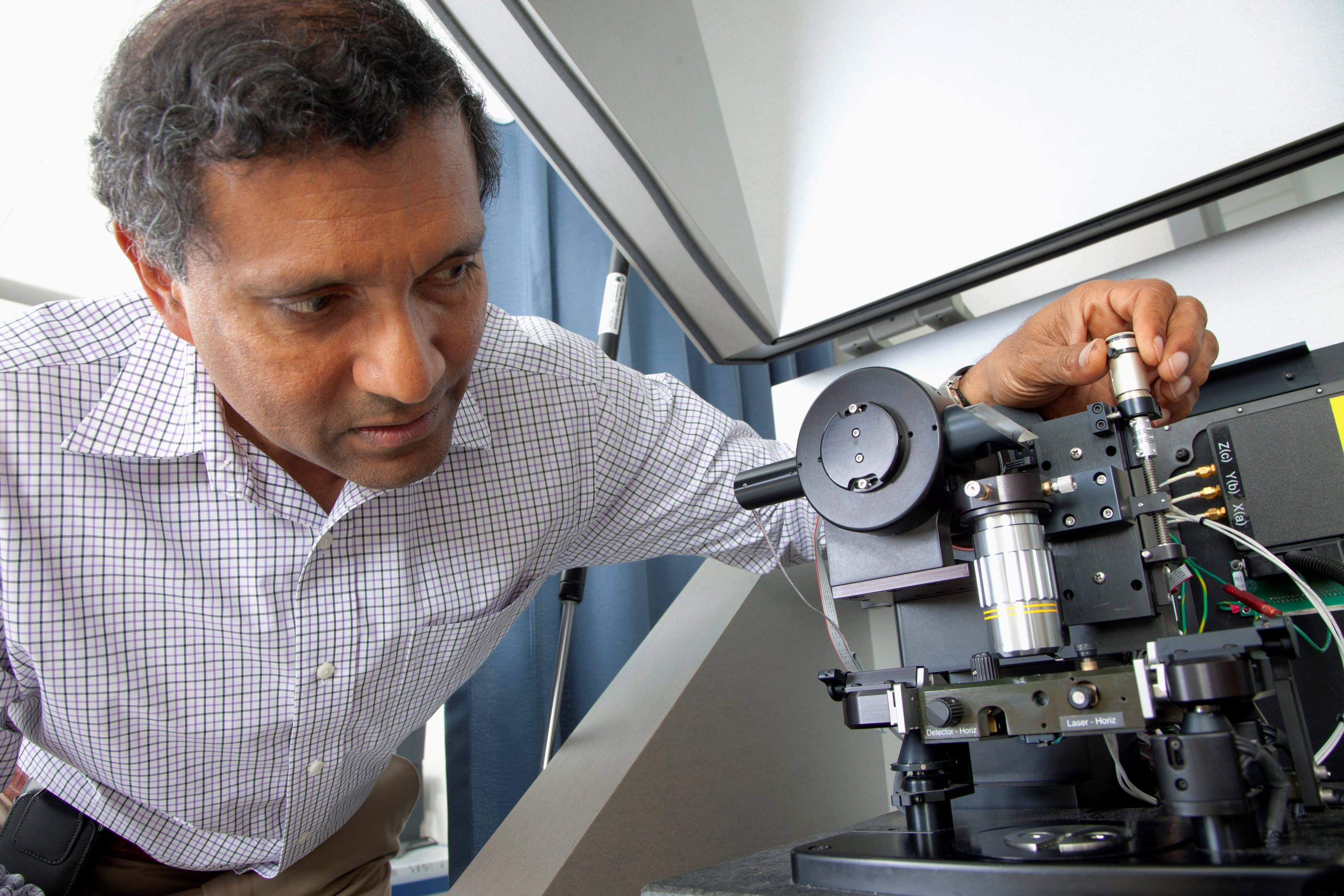

Burn care is just one side of Cinat’s work. As associate professor of clinical surgery, she also helps keep the center at the forefront of experimental research. For instance, UCI radiologist Joie Jones invented a non-contact ultrasound device that can determine burn-wound depth. Cinat says it’s 96 percent accurate, and so far used exclusively at UCI.

“What I like about research is finding better ways to do things, and having the ability to test them. It’s a way to participate in original thought. That’s why I stay at a university hospital,” she says. “I teach residents and medical students who are always asking questions that I may not have the answer to. It makes you a better person.”

Her patients say they’ve become better people, too.

Condiff regularly returns to cheer up depressed patients, and he attends the burn center’s annual holiday parties. “I feel at home and at peace on that property. I don’t think most people who leave a hospital want to go back and hang out there.”

His experience, Condiff says, “was one of the truly great blessings in my life. I know what’s important now. I know how people can care for each other. I say unabashedly that I love Dr. Cinat. My wife loves her. And we will love her forever.”

For Pastucha, who believes he’s on his way to full recovery, the results have been similarly life-changing. While he plans a return to his studio, he’s in touch with a different kind of inspiration. His burn experience, he says, has left him with the desire to do “loftier things,” such as mentoring for a children’s art project at the recent World Burn Congress in Baltimore, or helping supply silk murals as room dividers in the burn center to provide patients added privacy.

“I can’t say enough,” says Pastucha. “At the most devastating point of my life, to have someone that caring was not only reassuring, but inspiring.”