Port-wine stain masters

The Beckman Laser Institute & Medical Clinic at UC Irvine is home to one of the nation’s elite research and treatment centers for vascular birthmarks.

Most people have some sort of birthmark, a small skin blemish easily hidden under clothing or hair. But three out of every 1,000 American children are born with a larger type of birthmark called a port-wine stain that can significantly affect their quality of life.

Former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s forehead hosts perhaps the world’s most famous port-wine stain. These disfiguring vascular birthmarks — which literally look like red wine splashed on the skin — can cover large areas of the face, neck and upper body and left untreated can darken and swell into hard lumps, leading to bleeding and infections.

Dramatic improvements in laser removal treatments over the past decade have given dermatologists and surgeons greater ability to lighten or even fully remove these intrusive birthmarks.

The Beckman Laser Institute & Medical Clinic at UC Irvine is home to one of the nation’s elite research and treatment centers for vascular birthmarks. Directed by Dr. J. Stuart Nelson, the program treats hundreds of patients with varying forms of birthmarks with state-of-the-art technologies and procedures. Its doctors also use lasers to remove acne scars, sunspots and tattoos.

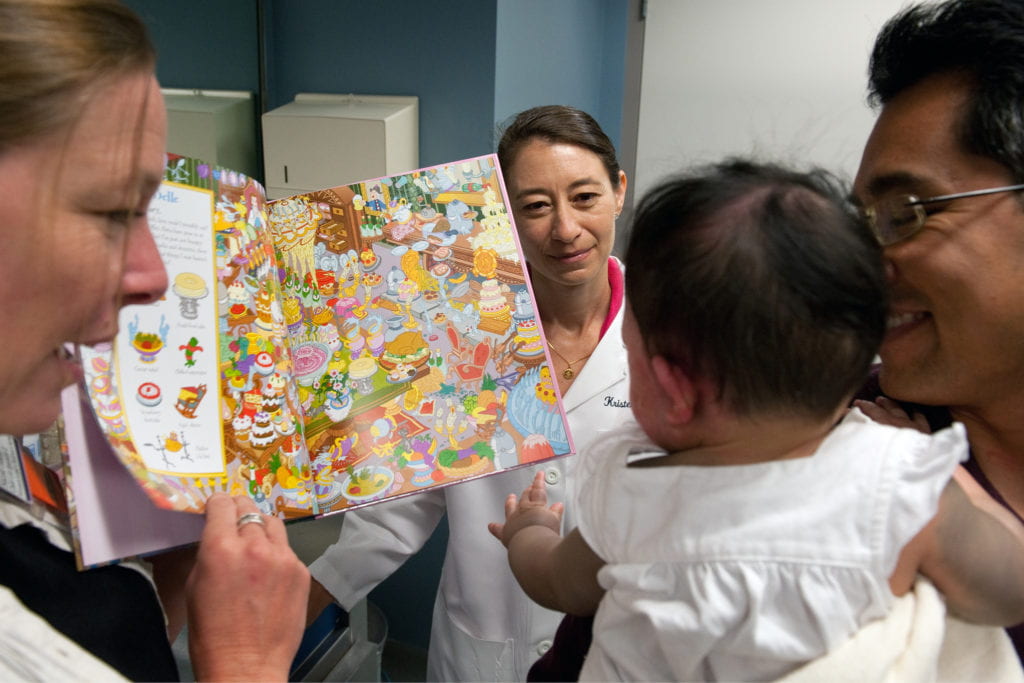

But the center’s primary focus is port-wine stains. More than half of patients treated for these birthmarks are infants like Alyssa Chhe, who was born late last year with a port-wine stain covering the left half of her face and part of her left arm. She also has glaucoma in her left eye, a condition associated with port-wine stains.

“Because of the safety of the laser procedures, you can start treatment very early, as soon as a few weeks after birth,” says Dr. Kristen Kelly, associate professor of dermatology and surgery who treats Alyssa. “The younger the patient, the better the chance for long-term success.”

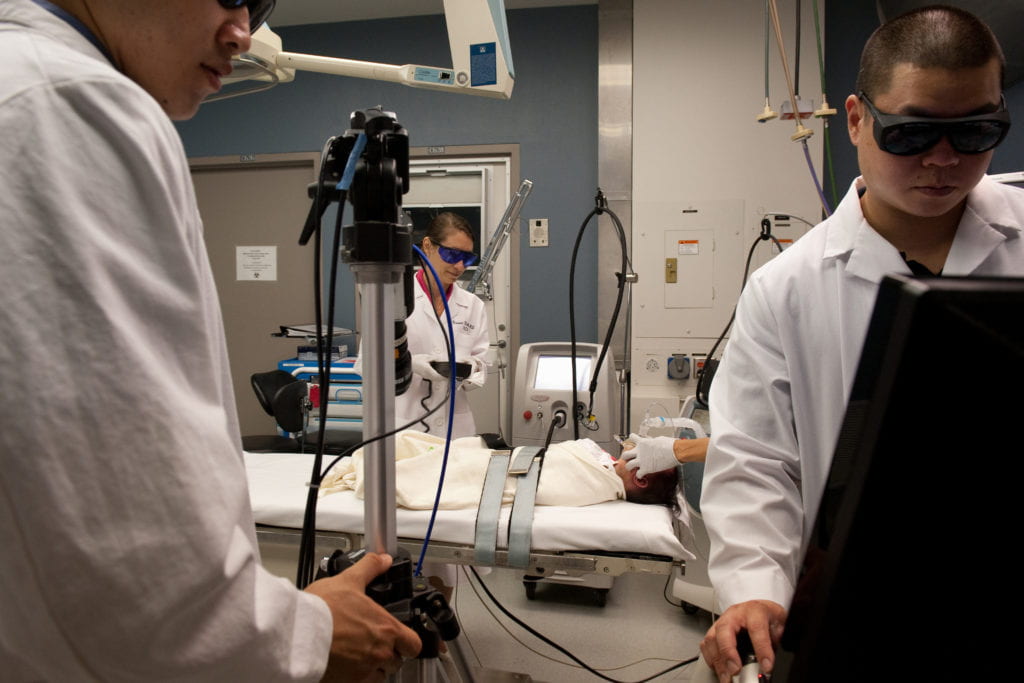

Alyssa received her first treatment when she was 8 weeks old. Her parents, Sophea Tim and Sothy Chhe, bring her to the clinic monthly for the 15-minute procedure. The anesthetized child is positioned on a surgical table that’s tilted slightly to allow more blood flow to her head. Using a pulsed dye laser, Kelly zaps port-wine stain blood vessels on Alyssa’s face and arm. The laser hand piece produces intermittent bursts of light as she works.

Kelly explains that the light is absorbed by hemoglobin within a blood vessel, heating it to the point that blood flow stops and the vessel eventually dies off. “It’s a very targeted therapy,” she says. “We use the laser to remove those vessels, and when you do that, you can remove the reddish color from the skin.”

A dynamic cooling device invented by Nelson is key to the treatment’s success, protecting the superficial layers of skin while allowing laser light to reach the subsurface port-wine stain blood vessels. Created in 1994, it’s now standard on dermatologic lasers.

“The dynamic cooling device was a significant improvement over the procedures previously available,” says Nelson, professor of surgery, dermatology and biomedical engineering. “With the DCD, the treatment became safer, and you could use much higher light dosages on younger patients without inducing adverse effects such as scarring or changes in the normal skin pigmentation. Furthermore, by cooling the skin, the DCD decreases the pain associated with the laser procedure.”

After six treatments, Alyssa’s improvement is noticeable — her burgundy-red birthmark has been reduced to a lighter rose color. The infant still has as many as nine more sessions to go.

“We’re pretty happy so far; there’s a visible difference,” says Tim, her mother. “At first we were apprehensive, thinking it would damage the skin. But Dr. Kelly has been very reassuring. She’s made us feel better. This can be overwhelming for parents.”

Treatment success depends on the size and depth of the port-wine stain blood vessels. One of the challenges dermatologic surgeons face is having these vessels grow back.

The Beckman team is looking for solutions. Kelly and Bernard Choi, associate professor of biomedical engineering, are using laser imaging to determine how many of the blood vessels are fully destroyed by laser treatment as a first step toward preventing their return.

They also are developing improved methods that combine new light devices with medications applied to the skin. Nelson notes that the center is currently hosting clinical trials to see if drugs normally used for immunosuppression and macular degeneration can fully block vessel regrowth.

“We’re distinctive that way,” he says. “Not only are we one of the biggest centers in the country for laser treatment of vascular birthmarks, but we’ve been leading the way for more than 20 years with breakthrough research making these treatments safer and more effective.”