State of the Art

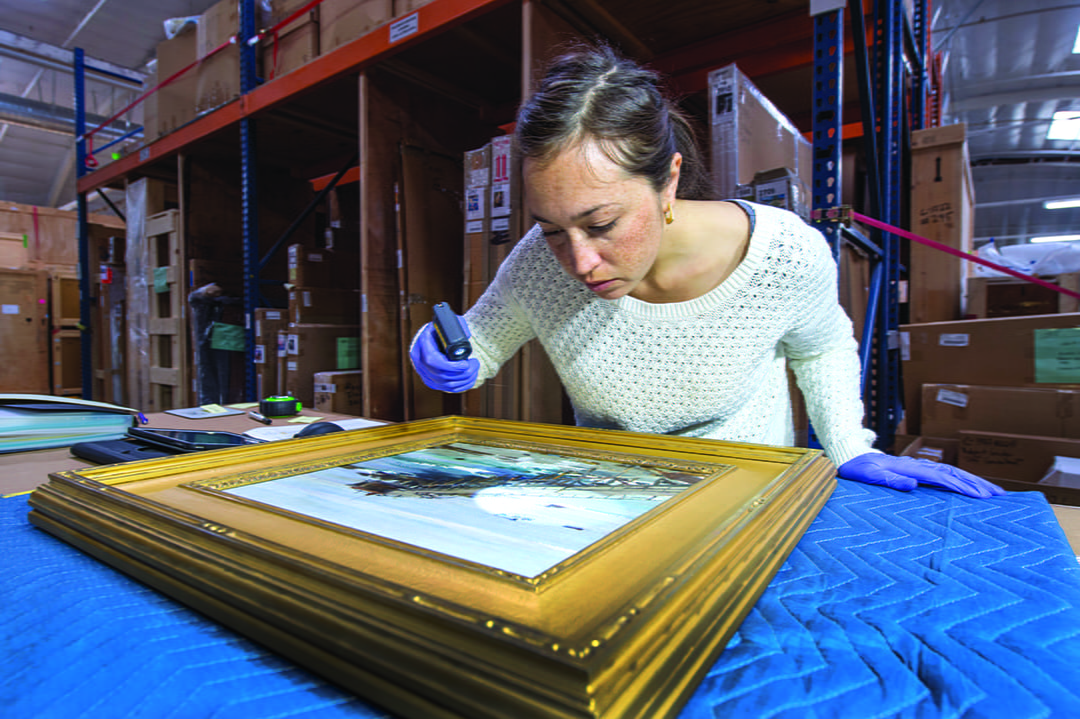

Inside an unmarked Los Angeles warehouse, a woman wearing disposable purple gloves uses a $300 specialized flashlight to pore over every inch of a crayon portrait. Framed by towering racks of artwork, she’s inspecting and inventorying a long-hidden stash of 3,200 paintings and statues bequeathed to

UCI by Orange County developer Gerald Buck.

The collection, a who’s who of California artists that comes on the heels of 1,200 canvases donated by The Irvine Museum, has bewitched art cognoscenti and revived long-dormant plans for a museum on campus.

Although it will take months to finish cataloging Buck’s treasures (which encompass everyone from abstract painter Richard Diebenkorn to street artist Shepard Fairey) and several years to finance and build a museum, some of the masterpieces will go public much sooner. This fall, UCI hosts the first in a series of sneak preview exhibits.

Fittingly, a few of the featured artists – such as Los Four founding member Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, M.F.A. ’73 – taught or studied at the university during the art department’s maverick first decade, when UCI played a pivotal but mostly unsung role in California’s modern art movement.

“These collections are extremely significant for California and, ultimately, the nation,” says Ilene Fort, curator emerita of American art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “The depth and breadth is remarkable.”

Museum Dreams

The earliest vision for a UCI museum appeared as a small rectangle on architect William Pereira’s 1962 blueprint for the campus. Although the idea was eventually scrapped (like the football stadium he also diagrammed), the location proved rather prophetic.

Almost six decades later, the building that will house the Buck and Irvine collections is expected to go up near the spot Pereira picked, which instead became the Irvine Barclay Theatre.

An architect and a curator could be chosen by January, says Stephen Barker, dean of UCI’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts and executive director of the nascent project, currently dubbed the Institute and Museum for California Art. “We’ll probably select a California design firm because this is a museum of California art,” he adds. The provisional plan calls for a 100,000-square-foot structure – with 45,000 square feet earmarked as gallery space, slightly smaller than the 50,000-square-foot Broad museum in downtown L.A.

Once the building opens, an army of docents will be deployed to answer questions, especially about sometimes difficult-to-decipher modern art pieces, Barker says.

As a teaching museum, the center will also include a research institute devoted to interdisciplinary studies of California art, a largely unexplored scholarly field. “I’m looking forward to being able to walk to the collection with a group of undergrads and have them experience paintings and sculpture firsthand,” says Kevin Appel, chair of UCI’s art department. “Students these days tend to look at artwork on a computer screen, illuminated from the back in ultra-sharp resolution. This is incredibly misleading compared to how a painting actually affects the senses.”

To cover the museum’s projected multimillion-dollar cost, UCI has begun courting donors and offering “multiple naming opportunities,” Barker says, ranging from galleries to naming the museum itself.

“It will definitely get built,” he adds, “but why stop there?” Barker dreams of having the museum anchor an “arts and culture district” that would extend past Langson Library to the edge of Aldrich Park and include an outdoor sculpture garden, food trucks, musicians, the New Swan Theater and other entertainment to further entice the general public. “In the end,” he says, “we’ll do as much as we can pay for.”

A Tale of Two Collectors

As soft jazz pours out of a dusty Sony radio in the L.A. warehouse, inventory taker Chanelle Mandell marvels at the eclectic nature of Buck’s art trove. “You don’t know what you’re going to see next,” she says, referring to the newest ration of unopened boxes. On this morning, the lineup includes a bronze lamb, a Russian immigrant’s depiction of Laguna Beach and a tile-and-wood disk of unknown origin. (“That’s for someone who went to grad school to identify,” quips Mandell, who previously worked at LACMA.)

It takes about half an hour to inspect, measure, photograph and log each piece. Occasionally, Mandell dons a magnifying visor to scour for cracked paint and other subtle damage. She also discards outdated packing materials, such as bubble wrap and glassine, which are replaced with archival foam and plastic by a former museum guard who works in the temperature-controlled building. Over the summer, two grad students will join the inventory team. But the collection is so vast that Mandell doesn’t expect to finish until next spring.

Buck, who lived in the seaside community of Emerald Bay, began buying art in the 1980s. His stockpile grew slowly over three decades, in contrast to Joan Irvine Smith’s, which ballooned to 4,000 works in just two years. “Smith was like a vacuum cleaner when it came to California impressionists,” says Susan Landauer, an art historian and veteran curator. The Irvine Co. heiress was equally speedy about putting her canvases on public display, opening The Irvine Museum in 1993.

Buck, meanwhile, kept his pieces mostly under wraps.

“His home was like a museum,” says Landauer, and when he ran out of room there, he converted a former Laguna Beach post office to a private gallery and used an old sail manufacturing plant as a storage facility. A self-taught scholar who flew under the art world radar, Buck invited only a few guests to the renovated postal building, where he acted as curator, docent and janitor. “He mopped the place himself,” recalls LACMA’s Fort.

But, like the Irvine family, Buck aspired to share his discoveries with a larger audience. “He wanted to have schoolchildren come visit the Laguna gallery,” Fort says.

In 2012, the year before his death, Buck hired Landauer to edit a comprehensive book about his collection, intending it to accompany a traveling exhibit called “Art at the Edge of the Pacific.” One of the essayists she recruited, author Jonathan Fineberg, met Buck for lunch in 2013 and pitched the idea of linking his art to a university. In a subsequent email, Fineberg – who was about to join UCI as a distinguished visiting professor – touted the campus as “a very good match.”

Buck, still mourning the recent death of his wife, Bente, and contemplating his own mortality after being diagnosed with throat cancer, leaped at the proposal. “Since our discussion, I have not been able to remove from my mind your brilliant idea … of developing a California art research center using the Buck Collection … and affiliating it with a major educational institution,” he wrote in a July 2013 email to Fineberg.

But five weeks later, before anything could be finalized, Buck succumbed to his illness.

The book project and exhibit were canceled, and Fineberg feared the collection would be auctioned off. It was another year before an estate lawyer phoned him to reveal that Buck had amended the family trust at the last minute to donate his paintings, sculptures and 6,000-volume library to one of four tax-exempt institutions, with UCI listed as his top choice. When arts dean Barker learned of the bequest and thumbed through a pair of thick notebooks detailing Buck’s holdings, he had to catch his breath. “I was just knocked out,” he says. “I couldn’t believe it.”

As if that weren’t enough, UCI heard from The Irvine Museum that same week about turning over its permanent collection to the campus. It took until 2016 to negotiate the Irvine deal and until late 2017 to resolve tax and legal issues surrounding the Buck gift.

Together, they’re a dynamic duo, says historian Landauer. The Irvine Museum’s publication of numerous books on California impressionism “helped legitimize” the genre in scholarly circles, she says. And Buck’s gems will have an even greater impact, she predicts. “Most art textbooks are New York-centric, and Buck desperately wanted to change that,” Landauer says. “This museum represents the culmination of his dream to insert California art into the larger narrative of American art.”

Best Kept Secret

Although often overlooked, UCI played a key part in shaping late 20th-century art, and Buck’s collection includes a healthy dose of Anteater professors and alumni from the 1960s and ’70s.

“Some of the most influential artists of the time were there,” writes curator Grace Kook-Anderson in Best Kept Secret, the exhibition catalog for a 2011 Laguna Art Museum retrospective on UCI’s formative years. The roster of faculty and visiting teachers back then included pop artist David Hockney, optical maestro Robert Irwin (who later designed the Getty Center’s Central Garden), photorealist Vija Celmins, plastic sculptor Craig Kauffman and other rising stars.

The result was a freewheeling cauldron of experimentation and creativity, says Tony DeLap, a founding professor and internationally acclaimed artist who painted murals in Disneyland’s Tomorrowland before coming to UCI, where he taught for nearly 30 years.

One instructor, cube creator Larry Bell, had students scrutinize the composition of cigarette butts lying on a sidewalk, according to Kook-Anderson. Painter Ed Moses urged his classes to wedge crayons between their toes. And DeLap invited a magician to guest lecture.

“There were a lot of weird people then,” says James Gill, a pop art luminary who made a cameo teaching appearance in 1969 and has seven pieces in the Buck Collection, including the crayon-on-Masonite portrait “Man in Striped Tie.”

Some art students proved just as unconventional. One created all his work underground, DeLap recalls. Another, James Turrell, a Quaker who had studied perceptual psychology and astronomy as an undergrad, tinkered with high-intensity light projectors to make eerie, glowing boxes. (He later purchased an extinct volcano in Arizona and began transforming it into a celestial observatory with futuristic tunnels and chambers.)

Alexis Smith ’70 started reinventing collages as a student, eventually incorporating such offbeat elements as steering wheels, bowling balls and neckties.

Perhaps the most unforgettable alumnus was performance artist Chris Burden, M.F.A. ’71. Nicknamed “modernism’s Evel Knievel,” he once had a friend shoot him in the arm with a rifle as they stood in a gallery.

For his master’s thesis, Burden spent five days contorted inside a small locker at UCI, a stunt that befuddled a Los Angeles Times reporter trying to interview two of his peers. “We hope you don’t mind meeting us here,” one of his classmates told the writer, “but we wanted to include Chris, and he’s living in a locker this week.” The article, as recounted in Best Kept Secret, noted that “during the interview, [Burden] was nothing more than a voice coming from locker No. 5, his presence further made known by occasional clanky sounds as he shifted positions inside. It was a strange experience and possibly a great put-on. But according to Burden … he was exploring his personal reaction to living in darkness and confinement.”

Says DeLap: “Our students were not bound by the history of what you were supposed to be doing as a young artist.”

Coming Attractions

In harmony with that renegade spirit, a trio of current UCI professors chose “some of the most challenging, abstract and avant-garde works in Buck’s collection” for the future campus museum’s first sneak preview, says Cécile Whiting, Chancellor’s Professor of art history.

The process of winnowing the pool of canvases and 3-D objects from 3,200 to 50 was unexpectedly easy, says Whiting, who is co-curating the exhibit with Barker and Appel: “Somehow our tastes were absolutely congruent.”

After reviewing thumbnail pictures from the catalog, the group trekked to Buck’s Laguna Beach showroom and the Los Angeles warehouse to see their picks in person, then laid out the floor plan by moving miniature copies of each piece around scale-model replicas of two UCI galleries.

The display will be accompanied by a coffee-table book with essays and color reproductions of select Buck artwork, Barker says.

Leading up to the museum’s construction and opening, UCI officials hope to produce three exhibits per year, but first they have to find another venue on campus, because the Claire Trevor spaces are booked primarily for student art.

The university may also need to rent additional storage room now that other collectors are joining the donation bandwagon, Barker says. So far, about 50 pieces have been accepted, he notes, bringing the value of UCI’s art holdings to more than $75 million.

To ensure that the museum encompasses all genres, UCI hopes to add newer California art, Barker says: “We’re not going to neglect Hollywood, Disney or video art.” Adds Fort: “Whoever becomes

curator should have a lot of fun.”

A Who’s Who of Golden State Artists

Billed as “the greatest collection of California art that nobody has seen,” Gerald Buck’s gift to UCI straddles multiple genres and features some of the 20th century’s most renowned painters and sculptors. All were born and/or worked in the Golden State.

The artists include abstract master Richard Diebenkorn, “Cool School” fixture Ed Moses, post-surrealist Helen Lundeberg, figurative painter Joan Brown, Chicano icons Carlos Almaraz and Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, collage maker Alexis Smith and pop artists Wayne Thiebaud (who designed California’s palm tree specialty license plates) and Ed Ruscha, to name just a few.

Although Buck focused mainly on post-World War II West Coast works, he also scooped up smatterings of Mexican folk art, Danish pieces, even a Thai wood carving. Their fate in UCI’s California-themed museum is unclear.

Rounding out the UCI Institute and Museum for California Art will be Joan Irvine Smith’s assemblage of California impressionist paintings (also known as plein-air art). The Irvine Museum Collection encompasses such landscape legends as Franz Bischoff, William Wendt, Guy Rose, Granville Redmond and Anna Hills, along with bird specialist Jessie Botke and scene painter Millard Sheets (whose oeuvre includes the University of Notre Dame’s “Touchdown Jesus” mural).

Museum Sneak Peek

The first in a series of exhibits drawn from the Buck Collection opens this fall. Featuring such acclaimed artists as Carlos Almaraz, John Baldessari, Viola Frey, Robert Irwin, Roger Kuntz, Agnes Pelton, Roland Petersen and Alexis Smith, “First Glimpse: Introducing the Buck Collection” will include early 20th-century abstraction, 1960s light and space, pop art and assemblage. The exhibit’s curators are Stephen Barker, dean of the Claire Trevor School of the Arts; Kevin Appel, chair of the Department of Art; and Cécile Whiting, chair of the Department of Art History.

When: Sept. 29 through Jan. 5, noon to 6 p.m. Tuesday through

Saturday, except holidays

Where: UCI’s University Art Gallery and Contemporary Arts Center Gallery

How much: Admission is free. Parking is $10.

More info: See http://imca.uci.edu for directions, related lectures and holiday closures.

Originally published in the Spring 2018 issue of UCI Magazine.