Artful Horizons

CTSA students are passionate about giving back and fostering artistic endeavors

What does it mean to be part of a community? For Claire Trevor School of the Arts students, it often means focusing on the underrepresented, social justice, and communities lacking resources for arts and arts education.

Many CTSA students have overcome adversity and forged their pathways to UCI and beyond. They are establishing themselves in leadership roles, in diverse peer groups and in their communities.

Back when she was in high school in a small town in West Virginia, M.F.A. student Rachel Lykins helped start a theater program there. She did everything from acting to painting sets, and her mother made costumes. Lykins says CTSA not only has helped develop her professional skills but has invigorated her to pursue theater outreach in the Appalachians.

“The program at UCI is unique in that they let students guide their studies outside core classes – they foster a lot of personal growth,” she says.

Alberto Lule, who was formerly incarcerated, says he selected CTSA over other arts schools because of its great faculty and the resources the UC system provides. He was also drawn to CTSA because of its emphasis on building communities.

“I believe that artists today should engage with their local communities and allow the community to influence their artistic practice,” Lule says.

Other UCI arts students who are building bridges include a dancer who’s advocating for disability justice, an artist working toward more equity and inclusion, and a musician who wants to teach in underserved communities. We highlight their stories on the following pages.

Bradford Chin, M.F.A. ’23 | Dance

I crave to be free.

That feeling has never subsided.

Can you tell me what freedom looks like?

Paint a picture for me?

These lines, written by a disabled performer, were part of Bradford Chin’s recent thesis choreography that was included in a graduate student showcase in April.

Chin’s work featured two disabled dancers and incorporated the poem. The performance was an example of his longstanding interest in exploring disability justice in dance.

“For most people, the first thing they think about when they hear this is, ‘Oh, he’s working on teaching people with disabilities and choreographing for them,’ and yes, that’s part of it,” Chin says. “But really what I’m doing with my collaborators is investigating how ableism has seeped into everything we do in dance and looking at what disabilities can teach us about dance.”

Some disabilities, he notes, are invisible.

“What I tell people is that I’m sometimes disabled – where it doesn’t always impact my living experience in the same way it does a visibly disabled person,” Chin says. “I’m examining how this affects nondisabled-identifying folks, the primary population of people I work with.”

He adds: “Invisible disabilities can refer to anxiety or depression but also aspects of a person that don’t conform to people’s expectations of what a ‘functional’ person in society should look like.”

Born and raised in San Francisco, Chin was a pre-med student at Cal State Long Beach before he decided to pursue dance after an audition as a freshman. His first experience with disability in dance came during a choreography residency in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“It was an ‘aha’ moment,” says Chin, who has taught ballet, contemporary modern dance and improvisation in 10 states and internationally. He says much of his learning about choreographing pieces that include physically disabled dancers comes from the dancers themselves.

“I also pull from the postmodern dance tradition of looking at collaboration and democracy,” Chin explains. “I allow people to come into a work and help navigate what direction the rehearsal or process takes to help them take care of themselves and others.”

“I’m sometimes disabled – where it doesn’t always impact my living experience in the same way it does a visibly disabled person. I’m examining how this affects nondisabled-identifying folks.”

Bradford Chin, M.F.A. ’23 | Dance

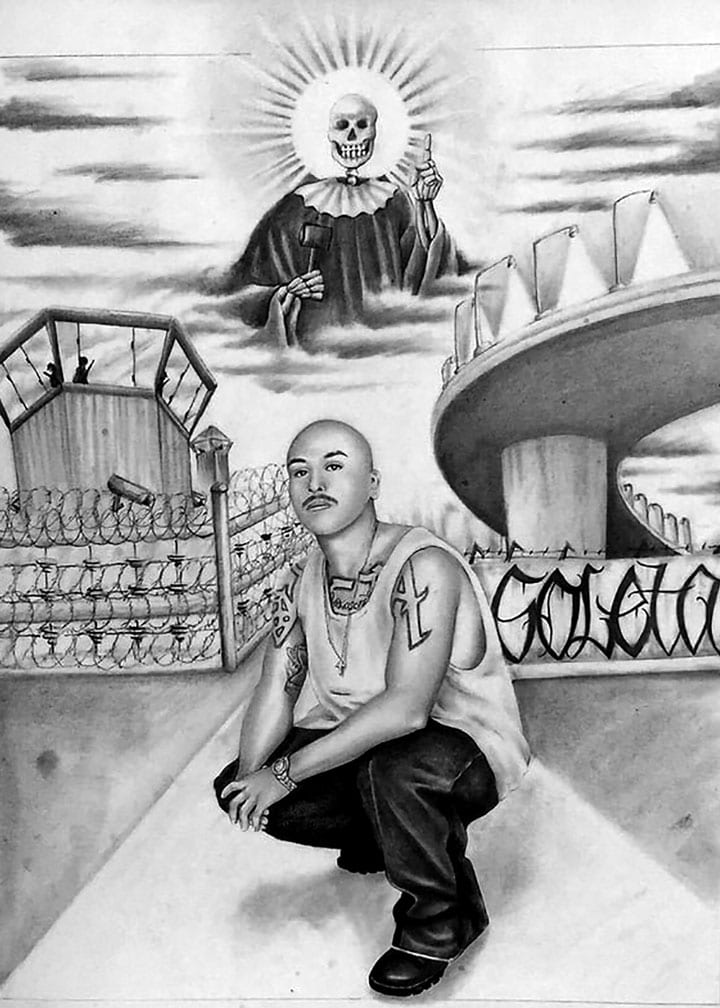

Alberto Lule, M.F.A. ’24 | Art

“Everything about me says I should not be in higher education,” Alberto Lule says.

During a nearly 14-year prison sentence for drug- and gang-related felonies, Lule took up drawing and studied

art history. Released in 2016, he enrolled in Santa Barbara City College, majored in art and completed his undergraduate studies at UCLA.

Now he’s a second-year M.F.A. student at UCI with a desire to give back.

“One of the things I always keep in mind is the second chance I was given,” says Lule, who’s married with a 17-year-old son and who commutes from mid-city Los Angeles to Irvine. “You’ve got to give back. I always try to find people to give that second chance to.”

Recently, Lule paired up with UCI criminology, law and society Ph.D. student Ryan Rising to teach art to detainees at Juvenile Hall in Orange.

“As opposed to the quality of their art,” he says, “we gear the lessons toward critical thinking – how the art makes them think and feel.”

Working with mixed media, Lule produces art that highlights the issues created by mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex, contrasting the different worlds of prisons and universities, for example.

“I use my experiences to create artworks that show the relationships between those institutions,” he says. “I believe that correctional institutions and institutions of higher learning are opposite sides of the same coin. I examine these places from an artistic perspective.”

Lule is vice president of the UCI chapter of the Underground Scholars Initiative. USI is geared to the formerly incarcerated and their families and others affected by the criminal justice system. “It’s a very hard topic to talk about,” Lule says. “At USI, people can come together and unpack that.”

He hopes to make an impact in the arts as a scholar involved with activism and solidarity.

“Art spaces could and should be places where activism can occur,” Lule says. “My dream is to transform galleries and museums into places beyond exhibitions where communities are created.”

“I believe that correctional institutions and institutions of higher learning are opposite sides of the same coin.”

Alberto Lule, M.F.A. ’24 | Art

Rachel Lykins, M.F.A. ’24 | Drama

Rachel Lykins played baby Jesus in her small hometown church when she was 2 months old, and the acting bug never went away.

The second-year M.F.A. student now hopes to return in a few years to her home state of West Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains, to establish a professional theater.

Lykins has already helped start a theater program at her high school in Huntington, West Virginia, that continues to thrive.

“A neat thing about the Appalachian Mountains region is that we have deep roots,” says Lykins, who majored in communication studies at Marshall University in Huntington and auditioned for the UCI M.F.A. acting program on a whim. “But because we’re so isolated, we don’t have access to a lot of things,” she adds. “I come from a theater desert.”

The Claire Trevor School of the Arts marked the beginning of Lykins’ formal theater training. A Medici Circle scholarship allowed her to enjoy, in 2022, what Lykins calls “the best summer of my life.” She spent it in Chautauqua, New York, with the Chautauqua Theater Company, developing the skills she will need to support her goal. Lykins served as assistant director for two new play workshops and gained insight into administration, artistry and community building.

“I’ve never grown so quickly,” she says of the experience.

At UCI, Lykins recently was in “The Story of Biddy Mason,” in which she played multiple roles, and she was the lead in “Airness,” about the world of air guitar competitions.

Lykins credits her UCI teachers for her growth as an actor. “The mentorship at UCI has been incomparable to me,” she says.

Before eventually heading back to West Virginia, Lykins says, she’ll pursue professional theater and film work.

“Storytelling has a lot of amazing properties to it,” she says. “Storytelling allows people to reflect and build community, and those are two things I want to help foster at home.”

“A neat thing about the Appalachian Mountains region is that we have deep roots. But because we’re so isolated, we don’t have access to a lot of things.”

Rachel Lykins, M.F.A. ’24 | Drama

Daniel Regalado-Ortiz, ’23 | Music

Daniel Regalado-Ortiz chats over Zoom from Taipei, Taiwan – a stop on a trip through Asia after completing a semester abroad at the National University of Singapore, where he just finished his remaining UCI undergraduate music courses.

Coming from a predominantly Hispanic section of Salinas, Regalado-Ortiz is intent on expanding his global lens – and teaching his specialty, the French horn, to people like him who come from lower-income communities.

Over the past year, Regalado-Ortiz has delved into various aspects of music: composing, arranging, teaching, performing and mixing.

Last year, he was a teaching artist intern in UCI’s Creative Connections program, which provides paid, yearlong teaching assignments to Claire Trevor School of the Arts majors at K-12 schools.

Regalado-Ortiz taught at Sierra Vista Middle School in Irvine. “I was surprised that there were over 300 students in the music program – and over 30 students in my beginning class alone,” he recalls. “That’s the same size as my high school band class.”

The experience, Regalado-Ortiz says, was great. Students had just resumed in-person learning and showed marked improvement over time. In his youth, however, music education wasn’t so readily available.

“There just wasn’t a lot of opportunity to study music growing up,” Regalado-Ortiz says. Two organizations, Youth Orchestra Salinas and Youth Music Monterey County, helped him develop his musical chops.

And his musical palette is expanding. “I’m an avid listener of lesser-known artists around the world and make personal playlists on Spotify,” says Regalado-Ortiz, who, aside from music, is well versed in current international issues and is an amateur sociolinguist. A first-generation college student, he looks forward to returning home to inculcate in youth a love of music.

“I plan on working with local after-school programs that are present in my hometown and become a music teacher,” Regalado-Ortiz says. “I want to give back to my community and help create a supportive music environment there. At the moment, there is a greater demand from the county to expand arts programs, and I believe that it is now the perfect time for me to contribute to it.”

“There just wasn’t a lot of opportunity to study music growing up. … I want to give back to my community and help create a supportive music environment there.”

Daniel Regalado-Ortiz, ’23 | Music

Khadijah Silva, M.F.A. ’24 | Art

Khadijah Silva believes art can be a platform to speak about social injustice, provide a voice to the underrepresented, educate others and effect social change.

She has witnessed firsthand the transformative power of art.

Born to a Black mother from the U.S. and a father from Mexico, Silva and her three siblings experienced homelessness as youngsters due to parental health issues.

She also weathered systematic racism and social injustice in and outside school. Due to her skin color and socioeconomic status, Silva often found herself isolated and disregarded by her teachers.

“My siblings and I always had straight A’s, and I always did art as a way to express myself, my struggle, my reality,” she says. “Education, for me, was the safety net.”

Silva attended high school and community college in the Bay Area. It wasn’t until community college that she considered art as a career. She studied under a mentor, Titus Kaphar, a prominent artist of color.

“It was the first time I ever saw a Black person doing research and teaching art,” Silva says.

She transferred to UCLA and earned a B.A. in fine arts in 2018.

The recipient of a Claire Trevor Society scholarship at UCI, Silva mainly has been working with photography and tar paintings to speak on things such as displacement, stolen histories, conflicting power dynamics and colonialism. She often incorporates nudity in her work as a symbol of resistance and strength.

“I try to show what power looks like,” Silva says. “I’m trying to reclaim that power for myself and other people of color. Why does vulnerability have to be a weakness?”

She selected the Claire Trevor School of the Arts for her graduate education because she believes it will provide her with the curriculum and tools to move one step closer to her dream: becoming the first Black Chicana art professor at UCI.

“I want to inspire other students who look like me,” Silva says. “I want to empower students to reshape their worlds through critical inquiry and transformative creativity. I’m committed to equity and inclusion in the arts.”

“I’m trying to reclaim that power for myself and other people of color. Why does vulnerability have to be a weakness?”

Khadijah Silva, M.F.A. ’24 | Art