Declawing the ‘tiger mom’

Book co-authored by UCI sociologist debunks idea that Asian American academic achievement is due to unique cultural traits or values

One in four Americans today are either immigrants or children of immigrants. As the U.S. moves from a black and white society to a potpourri of racial and ethnic groups, researchers are turning their attention to why certain immigrant and second-generation groups are more likely to succeed. Asian Americans stand out for having the highest median household income and education level of all groups, including native-born whites, according to the Pew Research Center.

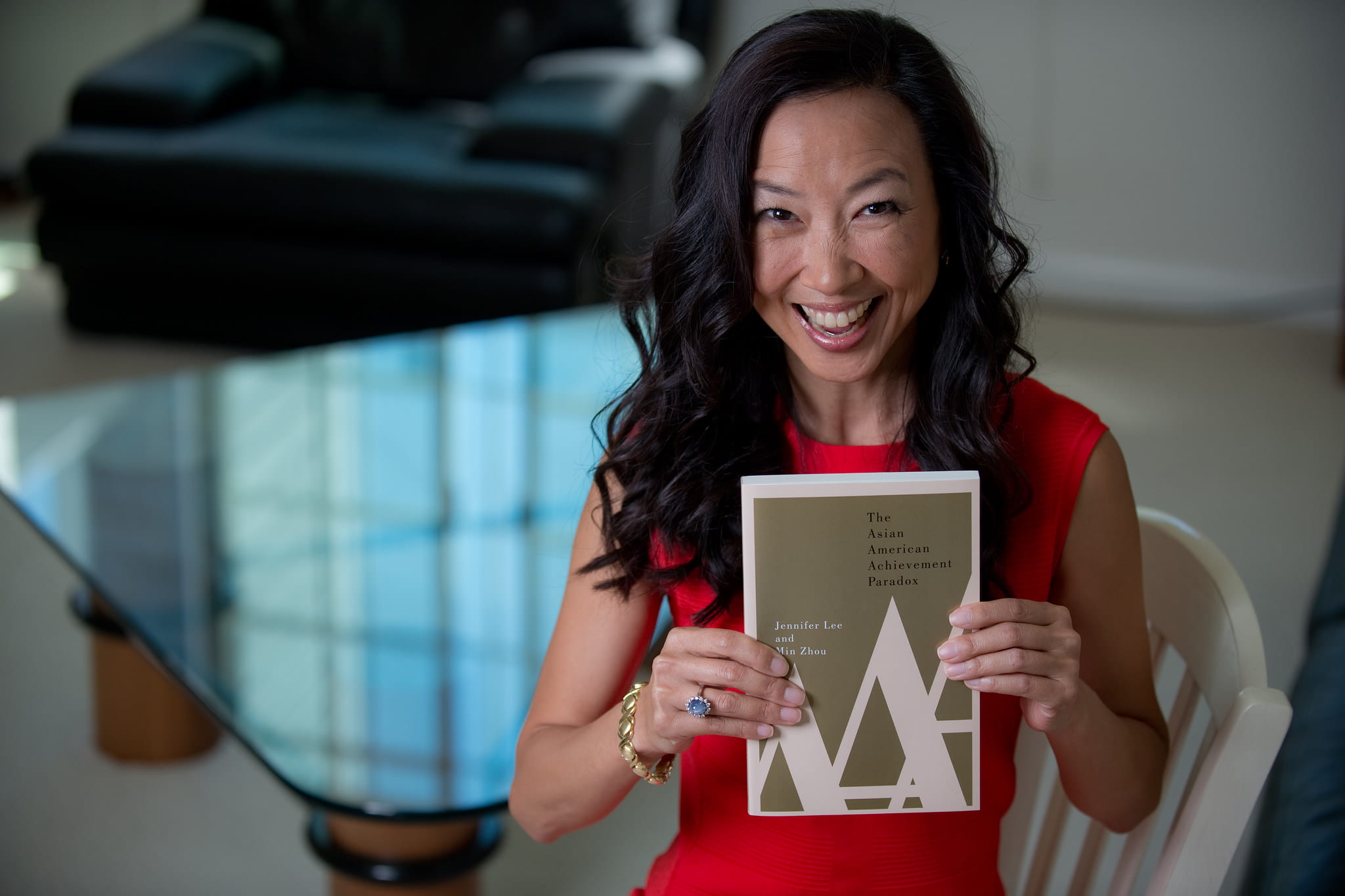

It’s a demographic that’s often stereotyped as the “model minority,” who seemingly get ahead because they have the “right” cultural traits and values. But there are very specific immigration patterns, institutions and social psychological factors that foster high academic achievement among certain Asian American groups, says Jennifer Lee, UCI professor of sociology and co-author of The Asian American Achievement Paradox – a forceful rebuttal to Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother.

Lee and colleague Min Zhou, professor of sociology and Asian American studies at UCLA, conducted 82 in-depth interviews with 1.5- and second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese people living in the Los Angeles/Orange County metro area. They also interviewed 56 1.5– and second-generation Mexicans, as well as 24 third-plus-generation, native-born whites and blacks for comparison. The book also includes census data and results from the Immigration & Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles study.

“Our research debunks the idea that there is something intrinsic about Asian culture, traits or values that produces exceptional educational outcomes,” Lee says. “First, the change in U.S. immigration law in 1965 was critical, because it ushered in a new stream of immigrants from Asia who are hyperselected – meaning that they’re more highly educated than their compatriots and also more highly educated than the general U.S. population.”

For example, only 4 percent of people living in China have college degrees, but about 51 percent of those emigrating to the U.S. do. In India, the vast majority of people are uneducated and impoverished, but 70 percent of its emigrants to the U.S. are college-educated. Moreover, these immigrants exceed the academic attainment of most Americans, 28 percent of whom are college-educated.

“The biggest predictor of a child’s success is parental education,” Lee notes. “If your parents are college-educated, the likelihood of you going to college and graduating is very high.”

The hyperselectivity of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. means their children begin their quest for success from more favorable “starting points” than do children of other immigrant groups, such as Mexicans, or native-born groups, including whites, she says.

Hyperselectivity can also benefit less fortunate members of an immigrant group, she says. After-school academies and SAT prep courses are popular in Asian American enclaves. The children of working-class immigrants in these areas can take advantage of these programs and services – many of which are offered by church groups and community centers at little or no cost.

Being a member of a hyperselected group, however, has social and psychological consequences, according to Lee. Since Chinese Americans are, on average, highly educated, people stereotype all members of this group as high achievers. As a result, teachers, guidance counselors and peers see all Chinese Americans (and all Asian Americans generally) as smart, hardworking and diligent and treat them accordingly.

These “positive stereotypes” can boost the performance of Asian American students – an effect Lee describes as “stereotype promise.” But the downside to being stereotyped by teachers as smart is that Asian Americans with less than stellar grades can view themselves as outliers or failures, she notes.

“Some of our interviewees said they don’t feel Asian or Chinese,” she says, “because their academic performance and career choices do not match what they perceive as the norm for Asian Americans.”

Lee says she took on the subject of Asian American educational attainment to foster understanding of how and why certain immigrant and second-generation groups succeed, a timely topic since China recently replaced Mexico as the top country of origin for immigrants in the U.S., according to the Census Bureau.

“Many people attribute Asian American success to intrinsic cultural traits or values, but our research refutes this,” she says. “In The Asian American Achievement Paradox, we show how the change in U.S. immigration law, access to material and nonmaterial resources, and the effects of racial stereotypes can influence group outcomes. These factors explain the high educational achievement of Asian Americans.”