Scenic spirituality

UCI exhibition explores role of faith in California landscape paintings

Summary

The “Spiritual Geographies” exhibition at UCI’s Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art explores how Sierra Club co-founder John Muir, Protestant ministers, theosophists and various painters used landscape art to transmit theological ideas.

Plenty of people see God in nature. But what about in paintings of nature? That’s the subject of a new exhibition – “Spiritual Geographies: Religion and Landscape Art in California, 1890-1930” – at UCI’s Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art.

On display from March 2 through June 8, the show explores how Sierra Club co-founder John Muir, Protestant ministers, theosophists and various painters used landscape images to transmit theological ideas.

Although the works contain no overt sacred symbols, religion “definitely informed a lot of landscape painting” around the turn of the last century, says curator Michaela Mohrmann. She developed the exhibition after noticing “spiritual undercurrents” in some of Langson IMCA’s collection.

In modern times, examining how religion influenced art has been largely taboo in museum circles, Mohrmann says. But that began changing a few years ago, she notes.

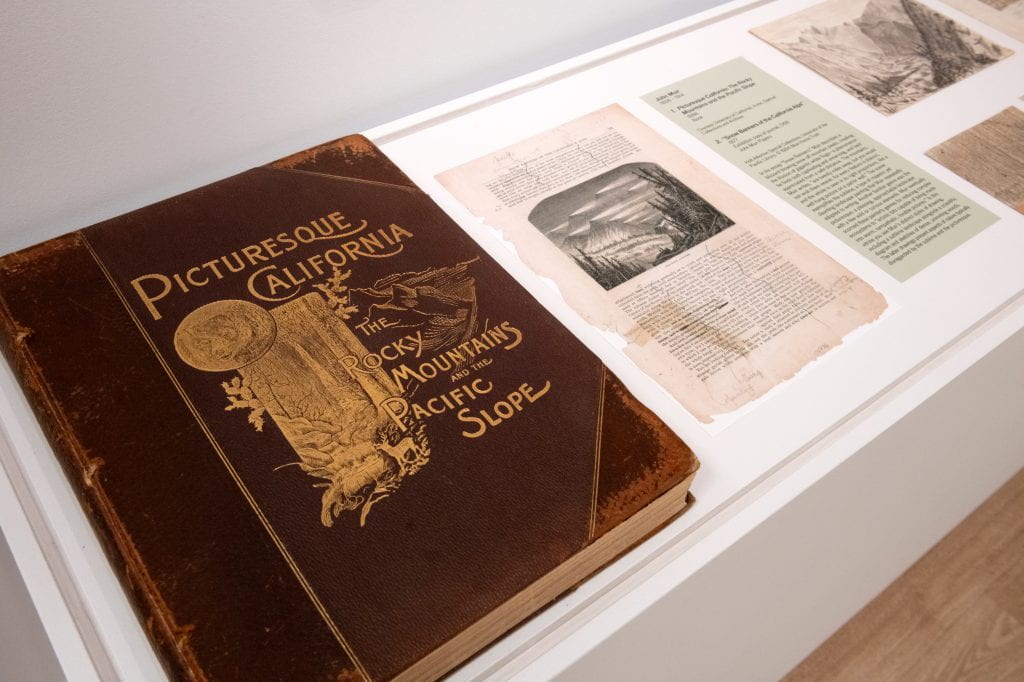

The first section of Langson IMCA’s show revolves around Muir, who memorized the Bible at age 11 and conjured mystical metaphors to lobby for preserving California’s wilderness. According to Mohrmann, he referred to God as an artist whose masterpiece was Yosemite Valley, compared being immersed in nature to baptism and wrote about “the sacrament” of sipping “Sequoia blood.”

From Muir the gallery segues to Protestantism, which in 19th century sermons and tracts invoked panoramic scenery as a pipeline to God. Some ministers even told their congregations to imagine biblical stories unfolding in California’s countryside instead of Israel, Mohrmann says.

German-born artist William Wendt, a pious Lutheran who married a Catholic sculptor and was known as the dean of Southern California landscape painters, titled some of his pieces after Scripture verses. But other names remained a mystery. Mohrmann discovered that one of the most puzzling, “Gentle Evening Bendeth,” was inspired by a now-obscure 1800s hymn. For viewers at the time, the effect was akin to watching a music video today, she says. Those who recognized the title would hear the song in their mind as they gazed at the art. Langson IMCA visitors can listen to the tune on headphones and read the lyrics in an 1894 hymnal on display nearby.

Unraveling the story behind “Bendeth” led Mohrmann to link other Wendt paintings to forgotten Christian anthems – and she hopes to publish a journal article about her findings.

The third wing of “Spiritual Geographies” features artists influenced by theosophy, a Point Loma-headquartered amalgam of Buddhism, science and occultism developed by Helena Blavatsky, a Russian transplant who claimed paranormal powers.

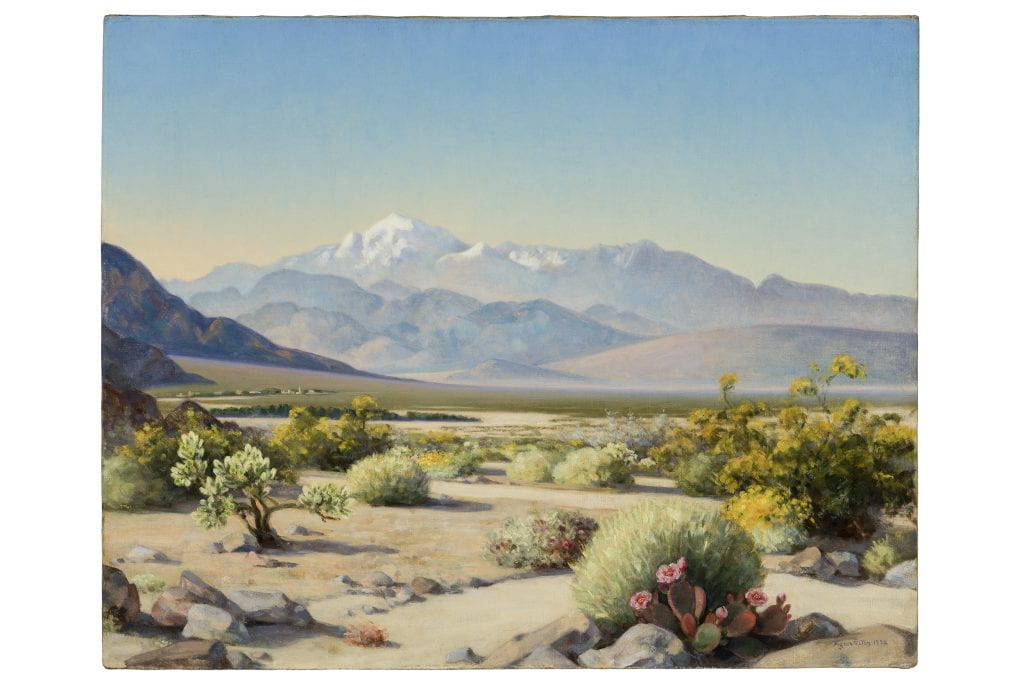

Agnes Pelton’s “San Gorgonio in Spring” depicts mountains that theosophists believed were spiritual guardians and home to a portal to another dimension. Artist Maurice Braun conveyed the sect’s reincarnation tenets by painting sycamores in different seasons, from withering summer heat to lush spring foliage, a subtle reference to cycles of death and rebirth, Mohrmann says.

The last stop on Langson IMCA’s spiritual art expedition highlights California’s network of Spanish missions – but not because the artists were Catholic or trying to impart church teachings. Rather, the 1884 novel Ramona had sparked a wave of public interest in these relics of the state’s religious past.

Many of the plein air paintings romanticized the missions, Mohrmann says, but there were darker interpretations too. The portrayals of crumbling architecture and ruins were seen by some as confirmation of Catholicism’s decline and Protestantism’s ascendancy.

All told, the exhibition spotlights 35 impressionist and early modernist paintings, along with an array of rare books, sketches, diary entries, newspaper clippings and other archival materials.

“This show is a love letter to my new home, California,” says Mohrmann, who was born in Texas but grew up in South America, Kentucky and France. “I hope visitors leave with an appreciation of the state’s complex history as a ‘spiritual frontier,’ shaped by conflict and persecution but also the ideal of religious tolerance.”

Full artwork credits:

John Muir, Picturesque California: The Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Slope, 1888 (1894 edition). Book. Courtesy University of California, Irvine. Special Collections and Archives

John Muir, “Snow Banners of the California Alps,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, v. 55, no. 326, 1877. Exhibition copy. 068 John Muir Papers, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library. © 1984 Muir-Hanna Trust

William Wendt, Gentle Evening Bendeth, 1938, Oil on canvas, 46 x 40 in. Courtesy of Hoefer Family Foundation

Agnes Pelton, San Gorgonio in Spring, 1932, Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. The Buck Collection at UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art

George K. Brandriff, The Bells of Old San Juan, between 1929 and 1933, Oil on canvas, 19 x 23 in. UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art, Gift of The Irvine Museum

William Adam, Back Corridor, San Juan Capistrano Mission, after 1894, Oil on board, 16 x 21 in. UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art, Gift of The Irvine Museum

George Gardner Symons, The Arches, between 1906 and 1915, Oil on canvas, 10 x 14 in. UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and Museum of California Art, Gift of The Irvine Museum