Early 1900s influencer anchors new museum show

Widow played unsung role in California art scene

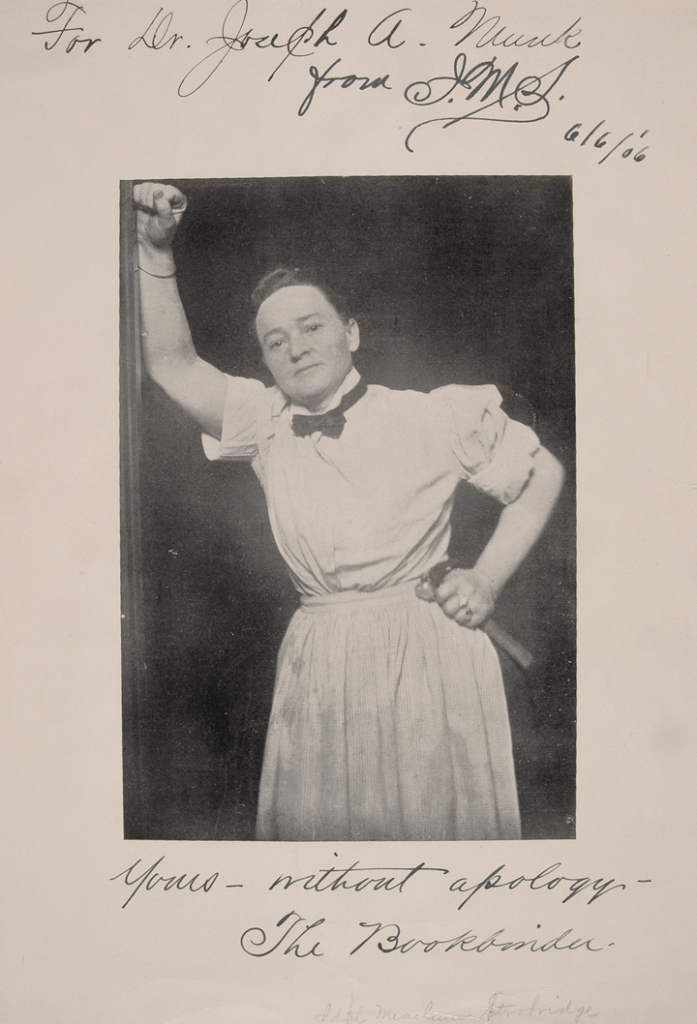

After running a Nevada gold mine, cattle ranch and book bindery in the late 1800s, Idah Meacham Strobridge moved to a bohemian hamlet near Pasadena and helped put a burgeoning California art movement on the map.

Her Highland Park gallery, the Little Corner of Local Art, launched noteworthy careers – and her adjacent bungalow, surrounded by rosebushes and live oak, served as a social hub for the painters, artisans and writers living along L.A.’s Arroyo Seco before the 110 Freeway came barreling through.

Strobridge, whose husband and three young sons succumbed to illness before her arrival in Southern California, was also a nationally known fiction author and genealogist.

But she soon fell into obscurity.

Her gallery and house were carved up into apartment units after she died in 1932. And her key role in California’s early 1900s art scene was either credited to others or relegated to footnote status, says Susan M. Anderson, an independent curator who is giving Strobridge her due in a new exhibition at UCI’s Jack & Shanaz Langson Institute & Museum of California Art.

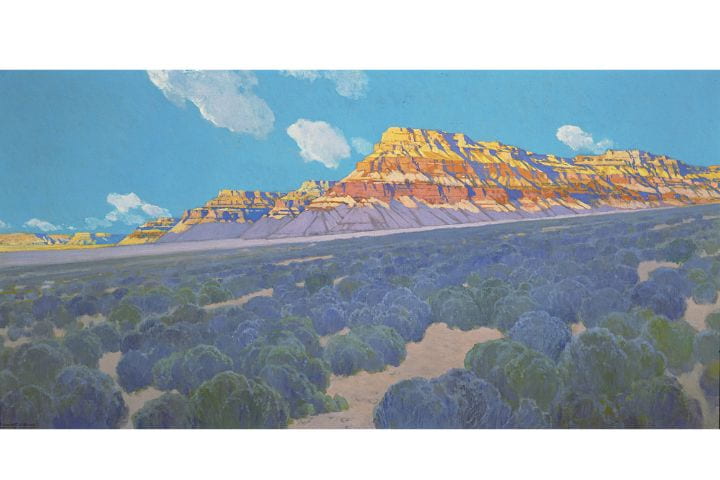

Running from Sept. 30 through Jan. 13, “Bohemian of the Arroyo Seco: Idah Meacham Strobridge” features Southwest-themed and plein-air paintings by the artists she promoted and is billed as “the first exhibition exploring the impact this pioneering gallerist and writer had on the development of Los Angeles culture” during the Arts and Crafts movement.

It’s the second time this year that Langson IMCA has resurrected all-but-forgotten figures from the past. In February, the museum showcased the Bruton sisters, a trio of celebrity siblings whose artwork dazzled the public in the 1920s and ’30s.

“New scholarship on California art, including under-recognized individuals such as Idah Meacham Strobridge … is proving to be a real differentiator for us,” says Langson IMCA director Kim Kanatani.

Curator Anderson came across Strobridge while researching Arroyo Seco artists for another exhibition. “She was more important than people realize,” says Anderson, who discovered through newspaper archives that several now-acclaimed artists – such as Hanson Duvall Puthuff and Carl Oscar Borg – gained prestige only after Strobridge displayed their work in her gallery.

Anderson also learned that California’s plein-air painting movement, which began in the Arroyo Seco around the turn of the last century, wasn’t initially tied to impressionism, as many assume. “It was a direct manifestation of the Arts and Crafts movement in Los Angeles,” she says. “The impressionism phase came later, around 1915.”

The UCI exhibition includes historical photos of the Arroyo Seco and Strobridge; signed copies of her books; and paintings of California missions, mountain scenery, Native Americans and Arizona landscapes by such Little Corner of Local Art stalwarts as Maynard Dixon (who also illustrated two of Strobridge’s short story collections), Granville Redmond, Fernand Lungren, Hernando Villa, and Elmer and Marion Kavanagh Wachtel.

In 1910, Strobridge closed her gallery, just five years after it had opened. “Her goal was to help artists get established,” Anderson says, and once that happened (in 1909, one of her shows drew sizable crowds and two local arts organizations sprang up), “I think she felt like she’d gotten things rolling and could get her life back.”

Strobridge stayed active in social and literary clubs, continued bookbinding, researched genealogies and, on Saturday nights, retreated to a former bathhouse in San Pedro, calling it her “substitute for the desert” where she grew up.

“I hope museum visitors will gain an appreciation of this overlooked woman and the Arroyo Seco artists she championed,” says Anderson, who has spent decades working on various California art history projects. “Through her gallery, books and bindery, Strobridge helped people understand what the Southwest was all about.”