UCI Podcast: Patsy Mink's role in Title IX passage

Co-authors of Mink’s biography share history of law designed to prevent discrimination on the basis of sex

Two congresswomen led the charge for Title IX in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s: Edith Green of Oregon and Patsy Mink of Hawai’i. Part of their motivation to spearhead this impressive and crucial legislation to mandate equity for women was born of their own experiences with exclusion. Mink was kept from her lifetime dream of becoming a doctor following rejections from more than a dozen medical schools because she was a woman. Her second choice as a career path, practicing law, was comparably littered with discrimination. And so began a political life devoted to change and advocacy, especially for gender equality and educational reform.

When Mink passed away in 2002, just a few months after the thirtieth anniversary celebration, Title IX was renamed the “Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.” In her speech at that celebration, Mink said, “On this 30th anniversary, let us rededicate ourselves to the goals of dignity, equality and opportunity for all that characterized our dreams for Title IX 30 years ago. These goals are every bit as worthy and important today, in 2002, as they were in 1972.”

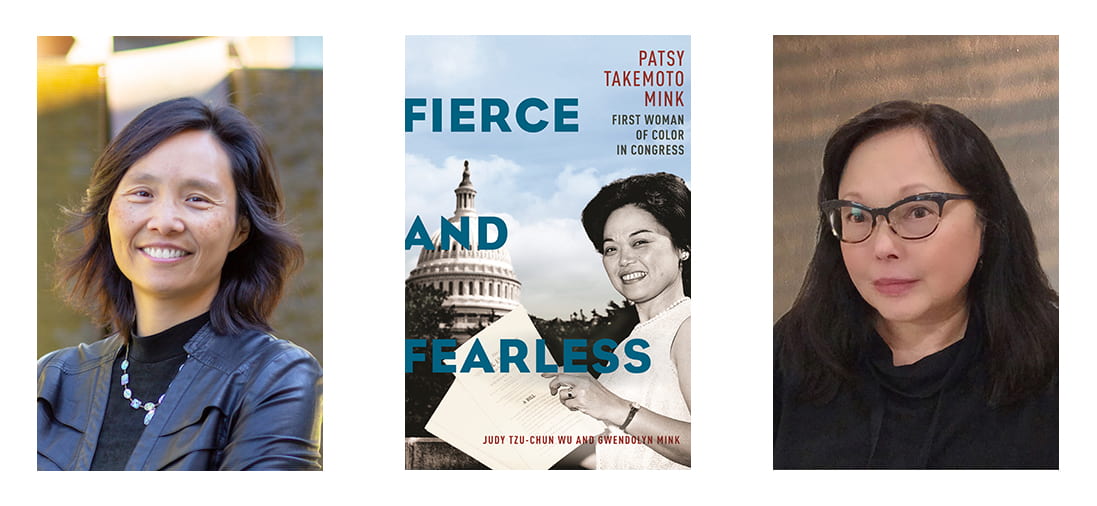

On June 23, 2022, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Title IX. In this episode of the UCI Podcast, Cara Capuano talks to the co-authors of the first biography of Mink, UCI professor Judy Tzu-Chun Wu and Gwendolyn “Wendy” Mink – Patsy’s daughter and only child. They discuss the book’s unique structure, the inspiration for Title IX, the challenges to get it passed into law, and what’s next for the landmark legislation.

Intro music for this episode of the UCI Podcast, “High Life” by the Mini Vandals featuring Mamadou Koita and Lasso, and outro music, “Savannah Sunshine” by Dan Henig, can be found in the Audio Library in YouTube Studio.

To get the latest episodes of the UCI podcast delivered automatically, subscribe at:

Apple Podcasts – Google Podcasts – Stitcher – Spotify

Transcript

From the University of California, Irvine I’m Cara Capuano and you’re listening to the UCI Podcast.

2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of Title IX. Signed then-President Richard Nixon on June 23rd, 1972, Title IX recognizes gender equity in education as a civil right.

Patsy Mink is considered the pioneer of the passage of Title IX. The first woman of color and the first Asian American woman to serve in Congress, Mink was a U.S. representative for the state of Hawai’i from 1965 to 1977 and again, from 1990 to 2002.

Today, we welcome to the UCI Podcast two people well-qualified to discuss Patsy Mink’s special relationship with Title IX, Judy Tzu-Chun Wu and Gwendolyn “Wendy” Mink. Judy Wu is a professor of UCI’s Asian American Studies department and also the director of the UCI Humanities Center. Wendy Mink served as a professor of politics at UC Santa Cruz from 1980 to 2001, then taught women’s studies at Smith College from 2001 to 2008. She’s also the only child of Patsy and John Mink.

The pair co-authored a newly released biography about Congresswoman Mink titled Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress. Thank you both for joining the UCI Podcast today.

Thank you for having us.

Thank you so much.

In the introduction, you address some of the big questions that you hope that this book will answer. Questions like: Who is Patsy Mink? Why is she not widely recognized among the feminist pantheon in U.S. history? How did a third-generation Japanese American from Hawai’i become such an influential voice in Washington, D.C.?

Each chapter begins with a personal vignette from Wendy. Then it continues with a complimentary historical narrative. Why did you decide to structure the book in that unique way?

It’s a slightly arduous story. Judy has a more economical way of answering the question, but I’ll lay the groundwork by saying that I had been puttering around my mother’s papers, which are housed at the Library of Congress, for several years before I met Judy and became aware of her interest in writing this book. And during the years that I was sort of treading water alone, imagining how I would write this book, I had a number of sort of intrapsychic episodes about what kind of voice I should deploy in the telling of the story and what my stance should be towards the subject of the story, my mother and the politics that she lived through.

The principal problem for me was trying to figure out a balance between the first person voice of the daughter telling the story and the third person “voice of the scholar,” sort of looking from outside with, you know, sort of dispassionate analytics skills to recount not only what my mother lived through but also the times that she was part of. And that was frankly paralyzing for me. It was very hard to figure out how to proceed because I couldn’t envision writing single chapters that used both voices. And on the other hand, I couldn’t escape my two selves in a way. And so, I didn’t really get anywhere until I met Judy who independently had embarked upon this project. And we developed a relationship over the subject that we were studying and decided to collaborate, thus making it possible to have two distinct voices represented in the work as a whole.

Yeah, it was really an honor to be able to collaborate with Wendy. I started the project 10 years ago for the 40th anniversary of Title IX. The Library of Congress was featuring the Patsy Mink papers and as a historian, I just crave archives. So, I was really excited to be able to delve into the collection. I had no idea it was so huge, and everybody said, “You should get in touch with Wendy Mink.”

It was just so wonderful to be able to go to the Library of Congress, do research in the archives, walk down the street, have dinner with her and talk to her about her mother and their family. We began with oral histories, but then when I found out that Wendy was asked by her mother to write her biography, it just made a lot of sense for us to collaborate together.

I think we had some conversation back and forth initially about whether the vignettes would go at the end of the chapter or the beginning of the chapter. And I think it works really well at the beginning to be able to hear from her these very moving accounts of her family, her memories. I think it really establishes a certain tone. And yeah, I’m really glad that our publisher, New York University Press, was supportive of having both of our voices. There were other presses who just said, “We only want the unauthorized biography. We only wanted the third person portrait.” And I think having this collaboration is much more in line with a feminist vision of what it means to recount somebody’s life. And to have this collaboration, I think is also reflective of Patsy Mink’s approach to politics as well.

It will mean something different to every reader, but for this reader – because I have started to read the book – I love it. I love the structure. I love the personal side. And then also the dive into the heavy nonfiction, you know, the real truth of kind of the history. It’s really brilliant. We’re going to primarily focus our conversation today on Title IX. And let’s just begin at the beginning. What inspired its creation?

I would have to say decades, centuries of discrimination and marginalization and subordination in the course of pursuing an education, or picking an educational path, that women encountered underlie, underpin, the movement to get the government to announce a gender equality principle for education as a civil right.

Since we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of the 1972 decision to enact a law that we now know of as Title IX, I’d have to say that the concept – pursuit of the concept of gender equality in education – probably emerged as part of the political discourse among people interested in women’s rights, people who were part of the emerging second-wave feminist movement in the mid 1960s. And as the sixties progressed, a cadre of policy feminists emerged in the grassroots and in women’s organizations who began to agitate and conceive of ways to show the significance of gender equality for educational opportunity for girls and women. My mother and her colleague, her senior colleague, Edith Green of Oregon, also a Democrat, also a member of the House Education and Labor Committee, struggled for a couple of years in the late sixties, beginning, maybe ’67, ’68, to try and figure out how to go about incorporating the concept in a legislative vehicle.

Basically, everybody kind of took as inspiration, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which included language that prohibited discrimination on the basis of race in any federal program. And so, the question was, how do we apply that same concept to prohibition on sex discrimination? Do we do it by trying to prohibit sex-based discrimination in any federal program? Is that a way to, you know, sort of include education while including a whole bunch of other things? Do we do it through the mechanism of a freestanding statute? Do we do it through some other kind of educational bill, making it sort of a piece of a much larger package? And, ultimately, that third option was what was decided on. And in 1971, the language that we know of is Title IX.

It wasn’t even called Title IX, per se. At that point, I think it was Title X. The language is incorporated into a large omnibus authorization package for education at all levels and ultimately goes through the legislative process, and ultimately hits Richard Nixon’s desk in June of 1972.

I’ll just add a little more about I think some of the personal motivation. Patsy Mink had wanted to become a doctor at a pretty young age and had really geared her educational career towards that goal. But she was applying for medical school in the aftermath of World War II, when the GI bill gave educational benefits, as well as mortgage benefits for returning GIs. And those slots, those educational slots, were really seen as the rightful possession of the men who were returning to school. And so, it was really a crushing blow for her to be able to not be able to study medicine. And she talks about that as being such a devastating impact on her life. And so, law was a secondary educational path and then eventually her career. And I think something else, which is that when her daughter, Wendy, was applying for college, a generation later, she was meeting with the same types of obstacles. One of the schools, which actually I went to, would write back and say, “You’re qualified, but we’ve met our quota of female students.”

So those types of educational exclusions, I think, really fueled both Patsy Mink’s desire, but also this collective generation of women who were seeking opportunities in education. And it was not just sports-oriented, but really all aspects of education. So, admissions, scholarships, entry into academic programs, housing, the climate of an educational institution, whether that was conducive for women to be able to achieve their aspirations. One of the mantras of the feminist movement at that time was “The personal is the political.” And so, I think these personal experiences of exclusion really fueled that fire to create opportunities of gender equity.

A law of this magnitude, like Title IX, and everything that you both just alluded to about what was happening at the time in the history of America – what were some of the biggest challenges that the team behind Title IX faced in trying to get it passed?

The challenge was not so much in getting it passed. The challenge was over how to define it once it was on the books and how to design its implementation and enforcement.

As I mentioned earlier, Title IX, the language of Title IX – the 37 words that are Title IX – was part of a humongous education bill. And in part, because it was part of a humongous education bill that contained other controversial matters such as school busing, desegregation, and federal student aid for college students and that sort of thing, it didn’t get the attention that would lead to controversy. So, it’s fair to say that Title IX was enacted without too much fanfare. There was grumbling along the way, there were pot shots at different aspects of it along the way, but it wasn’t kind of a raging controversy for anyone in 1972, mainly because it was overshadowed by other things.

If you look at Richard Nixon’s signing statement, he doesn’t mention Title IX at all. The whole thing is about school busing and desegregation and stuff like that. So, you know, it’s sort of slightly under the radar, shall we stay, but the 37 words had to be interpreted and had to be applied and had to be attached to an enforcement structure by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare at the time. It’s now under the jurisdiction of what became the Department of Education a few years later.

The process of defining and designing a structure of enforcement emerged over the course of three years, following the signing in 1972, and came to a head in 1975 when the new regulations were about to go into effect, which would be that Title IX would become a fully enforceable provision of law – a fully enforceable civil rights promise, or guarantee. During that period, tremendous controversy ensued and the biggest struggle that feminist policy activists, that feminists in the legislative branch – my mother, primarily, as well as her allies for women’s groups and so forth – was over the question of whether Title IX should be applied to athletics.

So, part of the reason why in the popular imagination athletics is so singularly sort of associated with Title IX in the public mind has to do with that early controversy. It was really sort of the main thing people talked about. The male athletics lobby mobilized, you know, steady feverish campaigns to try to win carve-outs in the enforcement of Title IX for athletics, for physical education and for other aspects of sports. And so, the proponents of Title IX, the people who were trying to defend Title IX to be a comprehensive policy in the enforcement phase – in the enforcement moment – had to struggle against the NCAA and, you know, college football teams and their coaches and all of the booster associations across the country that, you know, mobilized alumni to promote their, you know, male athletes and so forth. I mean, that was the biggest struggle during those early days.

Thankfully the struggle to preserve Title IX as comprehensive, without major exceptions for different pockets of education, will carry the day ultimately. And so, we move forward from 1975 with struggles over what the meaning of Title IX is going to be like: does it apply to sexual harassment? Does it apply to pregnant students and all of that sort of thing, not a struggle over who does it cover? Right? Does it cover math and science? Does it cover athletics? You know, I mean, those were the questions in the very early days.

I didn’t know why it was always so tightly associated with the athletics participation. And thank you, Wendy, for explaining that bit of history that when it was about to really be passed and, you know, enforced that was where it sounds like the primary resistance existed.

Yes, exactly. If the athletics resistance had carried the day, it had ramifications all across the board, right? Because then every male bastion in the educational project would try to get a carve-out for itself. So, it was kind of like a domino problem, but because it was so high profile, in terms of who was advocating for exceptions and the nature of the campaign against full gender equality. Yes, athletics was certainly what captured the public attention.

I was just gonna add a couple of things. One is that there was commentary about how extensive the lobbying was that it was just this barrage of letters and calls. And I think sometimes when, just as regular people, when we hear about the political process and we’re encouraged to participate, we don’t always know that it has an impact, but you definitely see politicians reacting, right? To letters that are being written to them and thinking that they need to respond in some ways. And I think for some of the political leaders, they were already inclined to be skeptical of Title IX. The other thing I just wanna share is that it was interesting to see the various ways to dilute Title IX. So, one of the amendments is saying, “well, we don’t necessarily have to withdraw federal funding from schools that practice unequal gender practices.” And so, I mean, that was the primary mechanism. Like if you are a school that receives federal funding, you have to follow or try to follow these guidelines. And so, they were just trying to – as much as possible – keep chipping away from the power of that legislation.

And we thought the political world was divisive right now. (laughter) You know, Wendy, you were a firsthand witness to watching your mom go through that time in the late sixties, early seventies, working with other feminists to try to make this happen. What did that look like for her?

Well, gosh, I mean, what did it look like? I mean, it was sort of something that was part of her consciousness on a daily basis for a number of years, right? Probably for a decade, I’d say – until she left the Congress, the first time she left the Congress in 1977. So, from ‘67 to ‘77, I’d say it was like front burner in her mind, but the form of – or the manifestation of – the Title IX struggle in life would vary with the way in which the issue was arising, you know. In the period leading up to enactment in 1972, I’d say that there was just a, a lot of back and forth with the feminist policy groups, the Women’s Equity Action League, in particular, sometimes with the National Organization for Women, and so forth, about how far out to go in public commentary about equity and education. You know, what kind of legislative vehicle to ultimately hang your hat on and things like that. Discussions that I was aware of, but didn’t involve all that much fireworks, right?

In the aftermath of passage, it was kind of like a Whac-A-Mole thing for her final four years in the House at that point, with all of these efforts to create carve-outs for athletics, but also for honorary societies. You know, the chemistry honorary society wanted to exclude women. So, like how can you have equity for girls and women in STEM fields if the science honorary societies are allowed to be male-only, right? It would come up that, “Oh, they wanna make sure that Father-Son Days at schools will be allowed. Therefore, we need to create a carve-out for Father-Son Days, which just creates this whole sort of checkerboard of exceptions and so forth.

So, there’s a lot of that sort of stuff that would come up in the form of amendments to other pieces of legislation that were not necessarily education authorization bills and things like that. And so, that was always something that I was aware of, you know, “Oh, what’s happening next or what’s happening now?” And it would be sort of every two months something would come up where, you know, some aspect of the anti-equality lobby would come up with a thing to crusade about that then the feminist defenders of Title IX would have to mobilize to resist.

One of the key ideas we talk about in the book is of Patsy Mink as a “bridge feminist.” And by that we mean that she’s a bridge between social movements and legislative activism. And so, she’s in conversation with women’s organizations, with people who are developing policy, and she’s trying to figure out how to collaborate with them so that she can introduce the most feasible ideas, the most powerful ideas in Congress. And I think that’s what Wendy describing – this relationship. And so, when people ask, “Is Patsy Mink the sole person responsible for Title IX?” she’s not the sole person because she’s really part of the larger movement that’s happening at that time. And I think this helps us understand better the process of passing legislation, but also the process of creating political change to not necessarily always focus on the one person – the one leader – but to think about people like Patsy Mink being in conversation, being in collaboration with movement activists.

What’s next for Title IX?

More struggle clearly. You know, athletic facilities across the country for girls and women are still unequal. Sexual harassment and sexual assault still plague women’s lives on campuses. Pregnant and parenting students still don’t have the necessary academic supports to continue their education in a consistent way. So, there are lots of issues that have been with us since the seventies, really.

In addition to that, there is always the specter of Title IX being taken away. Aspects of Title IX enforcement were seriously undermined during the Trump administration. So, that should be evidence of the threat. Should the Republicans come back to power, they… you know, I mean, not only can the implementing or enforcement regulations be rewritten, as they were under Trump, but the statute could be taken away. So, you know, just as it could be taken away legislatively – not by the court necessarily, but legislatively. So, there’s a lot to defend.

And finally, there’s a lot to do by way of public information and issue education in the communities that need to be able to deploy Title IX in order to assert their right to equity. You know, it took a long time for schools to even have Title IX officers, even though they were required to. Sometimes they would bury the job description in somebody else’s portfolio and so gender equity never got any attention at all. So, that’s a way of preventing people from knowing that they have rights that they can leverage against injustices that they feel that they’ve been exposed to. So, you know, “deploy, educate, defend” is the future of title IX.

Thanks so much, Wendy. I was just gonna share that I recently gave a presentation about Patsy Mink to a middle school and at least half the students were girls and neither had they heard of Patsy Mink, and they had not heard of Title IX. It was wonderful to be able to introduce both Mink, but also the significance of Title IX, and had them think about how it might impact their educational lives and their interests in sports, if it had not existed.

But I also try to talk to people about what is the value of law, right? Because you’re gonna have laws that mandate gender or racial equity, but how does that actually translate into lived realities? So, the differences between de jure and de facto. And I think it’s so important to have that legal principle in place. So there – at least – there’s a mandate, a national statement of principle that this is something that we aspire to as a society, but then how do we actually get there? And that’s the implementation, the enforcement, the public education.

It’s so important. Wendy, did your mom ever discuss with you the legacy that she wanted to leave?

No, I don’t think she ever used the word “legacy” in relation to herself. She did talk about – I mean, part of the reason she sort of “assigned me her biography,” shall we say – was not so much to illuminate a legacy, but to remember the struggles that are part of the political landscape of the late 20th century. She was afraid that people would forget, and either forget and then have to reinvent the wheel or forget and not learn from our passage to the present. So, there were a number of stories that she wanted to be sure were told from the standpoint of her participation in them, but not necessarily to celebrate, you know, anything in particular about her. So, I heard a lot about what we needed to remember in the 21st century that had been struggled through or resisted or accomplished in the 20th century. That sort of thing – that’s the kind of thing that she talked to me about.

Yeah. I was just gonna add a couple things. One of my favorite periods of Patsy Mink’s life is when she’s away from federal office. I think there was some uncertainty about what she would do with her life at that time period. She was middle-aged and it wasn’t clear that she would be able to go back to Congress, but she got involved with local politics. She entered the Honolulu City Council. And I just find that so admirable because people who are at the federal level don’t necessarily restart their lives at the local level, but I think she was just so committed to political change, protecting the environment, making sure that people who are marginalized have access, that she wanted to continue. And so, I feel like that’s her spirit. And when she passed away, she was still in office. She was still going. And even after she passed away, her constituency reelected her as a statement to honor her. So, I think that lifelong commitment to social change, lifelong commitment to social justice, is really a beautiful legacy that she leaves for us.

Absolutely. Thank you both for taking the time today to discuss Title IX and how it fits into the very rich history of Patsy Mink’s life with our audience.

Thank you so much.

It was great to meet you.

And Judy, as you mentioned – in the book, you do describe Patsy as “a lifelong fighter who demanded social justice. Someone determined to speak truth to power.” Someone who perhaps deserves more of your attention than just today’s podcast. Again, the title of the book is Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress – available for purchase at nyupress.org or for borrowing at the UCI Libraries.

The UCI Podcast is a production of Strategic Communications and Public Affairs at the University of Californ