The post-pandemic education landscape

UCI professor warns that coronavirus-prompted changes could worsen disparities in academic achievement between low- and high-income students

By the time school starts again this fall, students across the country won’t have set foot in a classroom for roughly half a year, at least doubling the usual length of summer break.

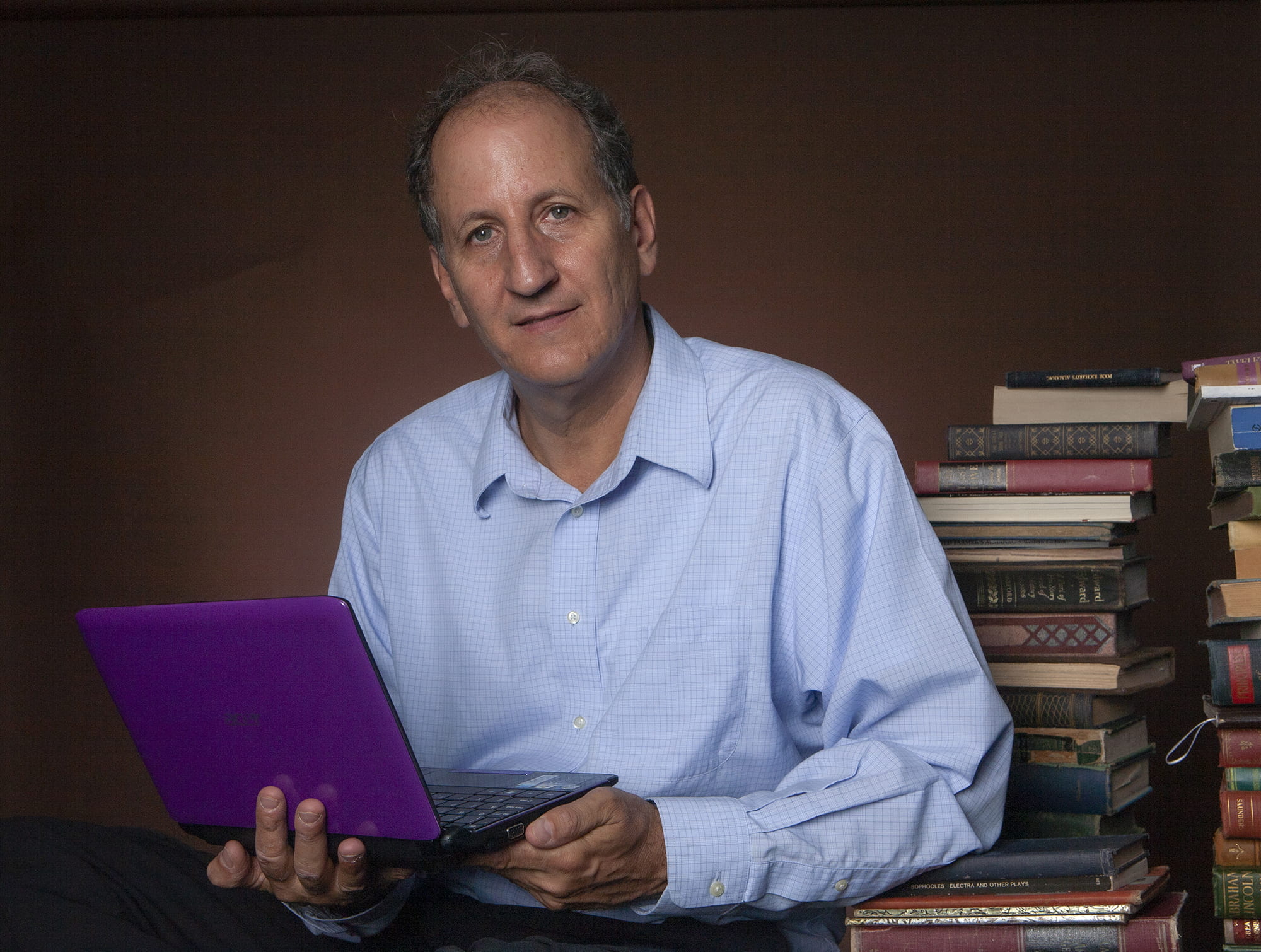

While many of them may celebrate what seems like an extra dose of vacation, those months out of the classroom threaten to widen the achievement gap between students from low- and high-income families, warns Mark Warschauer, UCI professor of education and an expert in online learning.

Summer break – not the school year – is when low-income students fall behind as their high-income peers attend enrichment camps or read easily accessible books. The double-long absence from school caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to leave less advantaged students with even more ground to make up.

“I’m worried about it, and everybody is worried about it,” Warschauer says. “This especially affects younger learners. When there’s a gap in reading or math at a young age, that tends to shape kids’ learning experiences their entire lives. If first- or second-grade students are falling even further behind in reading and math and there’s nothing done to deal with that, it’s going to have disastrous consequences.”

He and his colleague Di Xu, associate professor of education, lead UCI’s Online Learning Research Center, which aims to enhance online teaching and make it more equitable. The center offers resources for educators seeking to improve their virtual performance and conducts research on the most effective methods. Warschauer also directs the campus’s Digital Learning Lab, which seeks to understand how students learn in a digital environment.

Once the acute phase of the pandemic recedes and society adapts to a new normal, educators and officials will need to take steps to get students back on track, Warschauer says, with strategies that could include summer school, longer school hours or school on Saturdays. Funding those catch-up measures will be an entirely separate matter as the country slides into the worst recession since the Great Depression, he cautions.

School districts across Orange County and the country have scrambled to switch to remote teaching in the face of school closures. But low-income students might lack access to high-speed internet or computers – not to mention a quiet place to study and help from family members. This makes it challenging for them to keep up.

Warschauer has heard from teachers involved in research projects that many students in the Santa Ana Unified School District, which predominantly enrolls low-income Latino children, have been unable to participate in remote classes. National trends are similar. A recent survey by Education Week found that in early April nearly one-third of students in the poorest schools weren’t logging into online learning platforms or otherwise making contact with teachers – a percentage three times higher than in the wealthiest schools. And the hardest hit are often the youngest students who need the most in-person attention.

“If you’re a kindergarten teacher with kids with special needs in your class, and you’re in a low-income community and they might not have a laptop at home, it’s a total disaster,” Warschauer says. “It’s almost impossible to organize online education for young kids without in-person support.”

But even in higher education, remote teaching isn’t easy.

“There are a lot of students at UCI who come from low-income backgrounds who might not have internet access at home aside from their cellphone, which has limited data that might be shared with family members or others,” Warschauer says.

He thinks that the pandemic will accelerate the shift to educators including more online elements in their teaching. Online instruction was already growing before the coronavirus crisis gripped the country, but now an educator commuting two hours each way to teach in person may consider requesting more permanent online instruction abilities.

As society opens back up, students who are immunocompromised or otherwise at risk of severe infection may also be left behind, Warschauer notes. However, telepresence robots – like the one studied by UCI postdoctoral fellow Veronica Newhart – may gain wider acceptance.

UCI is equipping faculty to teach online. Nearly 100 applied to the Digital Learning Institute – a seven-week professional development program on remote teaching organized by the Division of Teaching Excellence and Innovation in partnership with the Online Learning Research Center. Sixty of those instructors will be selected for three different cohort sessions starting this summer. DTEI will also offer another program for graduate and postdoctoral students who are teaching this summer, plus 14 remote teaching webinars on various topics for all UCI faculty.

“University professors are currently dealing with a brand-new set of teaching challenges, and they have demonstrated exceptional creativity in finding ways to keep on teaching during this pandemic crisis,” says Megan Linos, director of learning experience design and online education at DTEI.

Students face major hurdles with remote learning. They are less able to ask teachers and peers for help. The camaraderie and sense of belonging are limited. They can’t drop by a counselor’s or tutor’s office for extra help. But perhaps most significantly, students who have less ability to self-regulate or study autonomously struggle with no teacher providing in-person support, Warschauer says.

In addition, many families lack the technology needed for students to effectively participate. High-speed internet access has actually declined in recent years as people replace cable internet with their cellphones. And while the majority of families have a computer at home, it may be shared by several people.

“I think our country needs to recognize that some kind of broadband internet access is imperative as a public utility,” Warschauer says. “We need to think very seriously about that.”

The rapid, pandemic-prompted switch to remote learning – while eased somewhat by the gradual trend in recent years of moving course materials online – will, no doubt, have long-lasting ramifications.

“I think in the future there will be a lot more attention on this,” Warschauer says. “People will have gotten a crash course in doing some kind of remote or online teaching, even if it was done under these circumstances.”