College makeover artist

UCI alum reboots Compton campus after fraud scandal

In a room full of disembodied mannequin heads, Keith Curry banters with students as they snip, comb and blow-dry the dummies’ hair. The newly opened cosmetology center is one of several stops on Curry’s Compton College makeover tour.

Other highlights include an artificial turf football field, a striking library complex and a nursing lab equipped with several $100,000 robotic patients, one of which can deliver a faux baby.

Since taking over the community college in 2011 – following a corruption scandal – Anteater alumnus Curry has slowly revitalized the 91-year-old institution, winning back its accreditation and persuading local voters to approve a $100 million bond measure to update the school.

But the overhaul has been no cakewalk. And more work remains.

When Curry arrived on campus as dean of student services in 2006, things were a mess. The school had been stripped of its accreditation – a first among California public colleges – and millions of dollars had reportedly vanished in a web of questionable perks for top officials, lax payroll policies and a scam that enrolled phony students.

To avoid a complete shutdown, state leaders made the campus – dotted with jacaranda trees, palms and aging brick buildings – a satellite of El Camino College in Torrance. Curry, who was born and raised in Compton, vowed to restore the school’s independence and reputation once he took the helm, a promotion that coincided with earning his doctorate in education through a joint UCI-UCLA program. (Curry’s dissertation was on Compton College’s accreditation debacle.)

His first project was renovating the campus’s transfer center, which recruits students at nearby high schools and churches with a combination of coffee mugs, T-shirts and free tuition for the first year.

“The transfer center is the catalyst for everything,” says Curry, who ran UCI’s Early Academic Outreach Program before starting at Compton College.

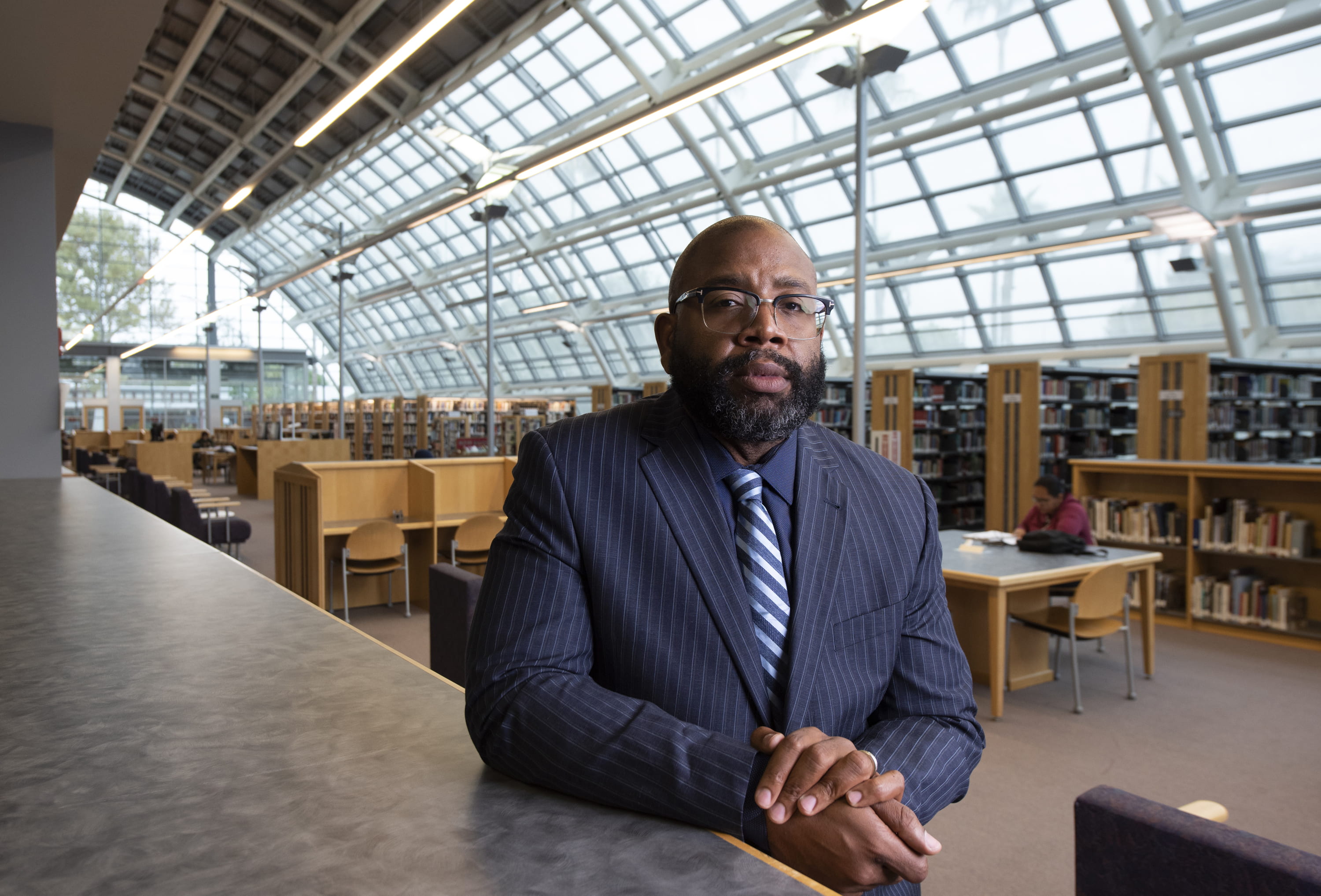

One of his signature undertakings was a $25 million library and student success complex, which opened in April 2014, partly as a marketing tool for what a proposed bond measure could accomplish.

“You’ve gotta give people hope,” he says.

It worked. Seven months later, the bond passed with 78 percent of the vote. The funds helped fuel various changes at the campus, including:

- Revamped programs in cosmetology and heating, ventilation & air conditioning

- New women’s soccer and softball teams

- A transition program for ex-convicts

- Campuswide Wi-Fi

More recently, Curry turned his attention to support services, opening a campus health center (in partnership with Molina Medical Management), a childcare center and a food pantry for undernourished undergrads. “I got so focused on student success that I forgot some basic needs,” he explains. In that vein, he also hopes to erect a 540-bed dorm for homeless college attendees.

Among other projects in the pipeline are a $31 million athletic complex and an $8 million performing arts center.

One venture that Curry has purposely avoided is a school recycling program. That’s because poor people regularly come through the campus rummaging for cans to sell, he says: “It’s their income, and I don’t want to take that away.”

Despite the flurry of activity, problems large and small remain. The school’s graduation rate – 34 percent within six years – is below the state average of 48 percent. Another challenge: Enrollment has slipped in recent years amid a demographic shift from 34 percent Latino in 2011 to 60 percent now.

But overall, Curry’s efforts have won favorable notice. Inside Higher Ed, a trade publication, recently featured him in a lengthy article about how Compton College bounced back from disaster.

In May, he was named one of four finalists to become president of Nevada’s largest community college. But Curry quickly withdrew his candidacy, stating that the metamorphosis at Compton College “is too important to me (professionally and personally) to leave at this time. … My work here is not done.”