A California Art Apostle

Running an art museum was not something James Irvine Swinden ever imagined. When his mother, Joan Irvine Smith, began feverishly collecting California impressionist artwork in the early 1990s, Swinden was happily operating a 12-acre botanical garden on the island of Kauai. So when she asked him to help set up a museum to showcase the pieces, he figured it was a temporary project.

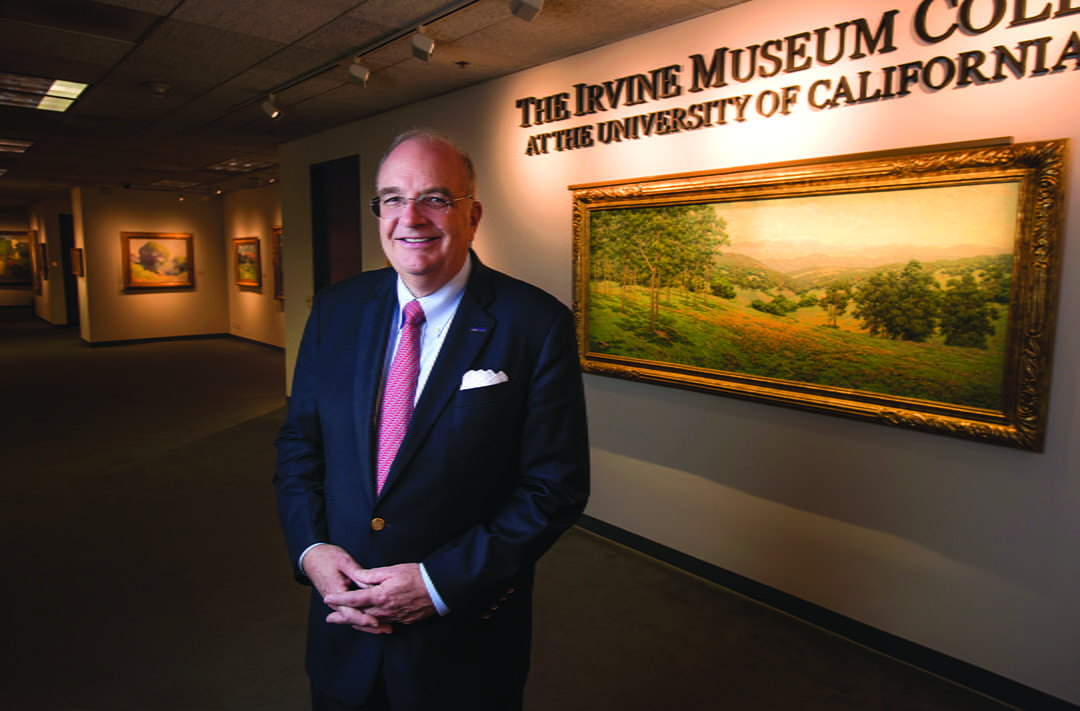

Instead, he soon became president and chief champion of The Irvine Museum, which debuted in 1993 to promote California plein-air painting, an outdoor style that focuses on light and color. Over the last quarter-century, Swinden has devoted himself to the genre, taking numerous works across the U.S. and even overseas.

Two years ago, the museum donated its permanent collection – a 1,200-piece assemblage that includes canvases by Franz Bischoff, William Wendt and Guy Rose – to UCI. Until the new UCI Institute and Museum for California Art is built, Swinden continues to shepherd The Irvine Museum’s exhibits, traveling shows and coffee-table books. He also gives talks about the collection. A lawyer and businessman by training (with degrees from Loyola Law School and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School), the fifth-generation Californian revels in telling behind-the-scenes stories about the museum’s artists.

On a recent afternoon, surrounded by paintings in his 12th-floor Irvine office, Swinden – who also chairs the advisory board for UCI’s future museum – sat down with UCI Magazine writer Roy Rivenburg to discuss art, ecology and Hawaii hurricanes.

Q: In 2002, The Irvine Museum organized the first tour of California impressionist art in Europe. What was it like bringing the Golden State’s version of the genre to its birthplace?

When we arrived in Paris, the head curator [of the Mona Bismarck Foundation Museum] was bubbling over with enthusiasm for the show. I was a little uneasy and asked her, “How can you be so confident about it?” She replied, “You see the two gentlemen over there who are installing your art for us? They’re the two best installers in Paris.” I said, “Well, at least we know the paintings will be properly hung.” She said, “No, no, you don’t understand. They just finished installing a Matisse and a Picasso show at the Musée d’Orsay, and they like your stuff better.” We broke attendance records at all three museums we went to [in Paris; Krakow, Poland; and Madrid]. It was great fun.

Q: You weren’t wild about art before launching The Irvine Museum. What changed your attitude?

Although I grew up surrounded by great art – my mother and grandmother had significant collections of Asian art and British sporting art – I never thought a whole lot about the works. They were just there. And when I went to college, I primarily thought I would go into real estate. During law school, I bought and renovated my first commercial property. I was highly successful in that field and later went on to purchase a botanical garden in Hawaii. I expanded its collection of tropical plants, focusing on protecting endangered species, and opened the house for tours. But financially, after two hurricanes [including a record-shattering 1992 typhoon that toppled 100 trees on the property], it didn’t quite work out.

My interest in art began when I was brought in to handle the financial and legal aspects of the museum. As I became more and more involved, it became a passion. I even started my own collection of California impressionism.

Q: What led your mother to create a museum devoted to California plein-air painting?

After collecting over 4,000 works in about a two-year span, she began to think about sharing them with the public, not only for their artistic merit, but as a way to create environmental awareness and inspire stewardship of California’s beauty and natural resources. Many of the paintings show California in a very pristine state. In some instances, those areas do not exist anymore. It’s a powerful message to people.

Q: What’s your favorite piece in the collection?

There are several that resonate with me. One is by William Ritschel: a nocturne of the sardine fleet coming back into Monterey Bay. Not only is it a great impressionist painting, but it speaks to how an industry self-destructed in about 10 years by overfishing. So it conveys the environmental message we like people to think about.

Q: You’re known for telling stories about artists. Whose background most intrigues you?

Granville Redmond. At age 2, he contracted scarlet fever and became deaf. He then chose not to speak for the rest of his life. After studying art in Paris, he returned to California, befriended Charlie Chaplin and decided to try acting. Chaplin put him in several films but ultimately realized Redmond was a much better painter than actor and became a patron of his artwork.

“Many of the paintings show California in a very pristine state. In some instances, those areas do not exist anymore. It’s a powerful message to people.”

Q: Were you excited to hear that The Irvine Museum Collection will be joined by a newer gift to UCI, Gerald Buck’s trove of California art?

Yes, the two collections enhance each other; their combination makes both more important. One thing I find interesting is that some of the paintings in my mother’s collection were purchased from Gerald Buck. So we’ve come full circle.

Q: You said your mother originally had 4,000 paintings. What happened to the ones that weren’t donated to UCI?

Some have been “de-accessed,” a fancy museum term for “sold.” Others are still in our private collections. About three and a half years ago, I started thinking about the sustainability of our collection and what the best purpose was for it. It seemed natural that it should go to the university my mother helped found.

Q: What impact will a campus museum have on UCI?

It takes the university to another, higher level. Art is one of humanity’s most significant endeavors. Throughout history, when you go back, almost everything disappears. Languages disappear, cultures disappear. But art and architecture last.

Originally published in the Spring 2018 issue of UCI Magazine.