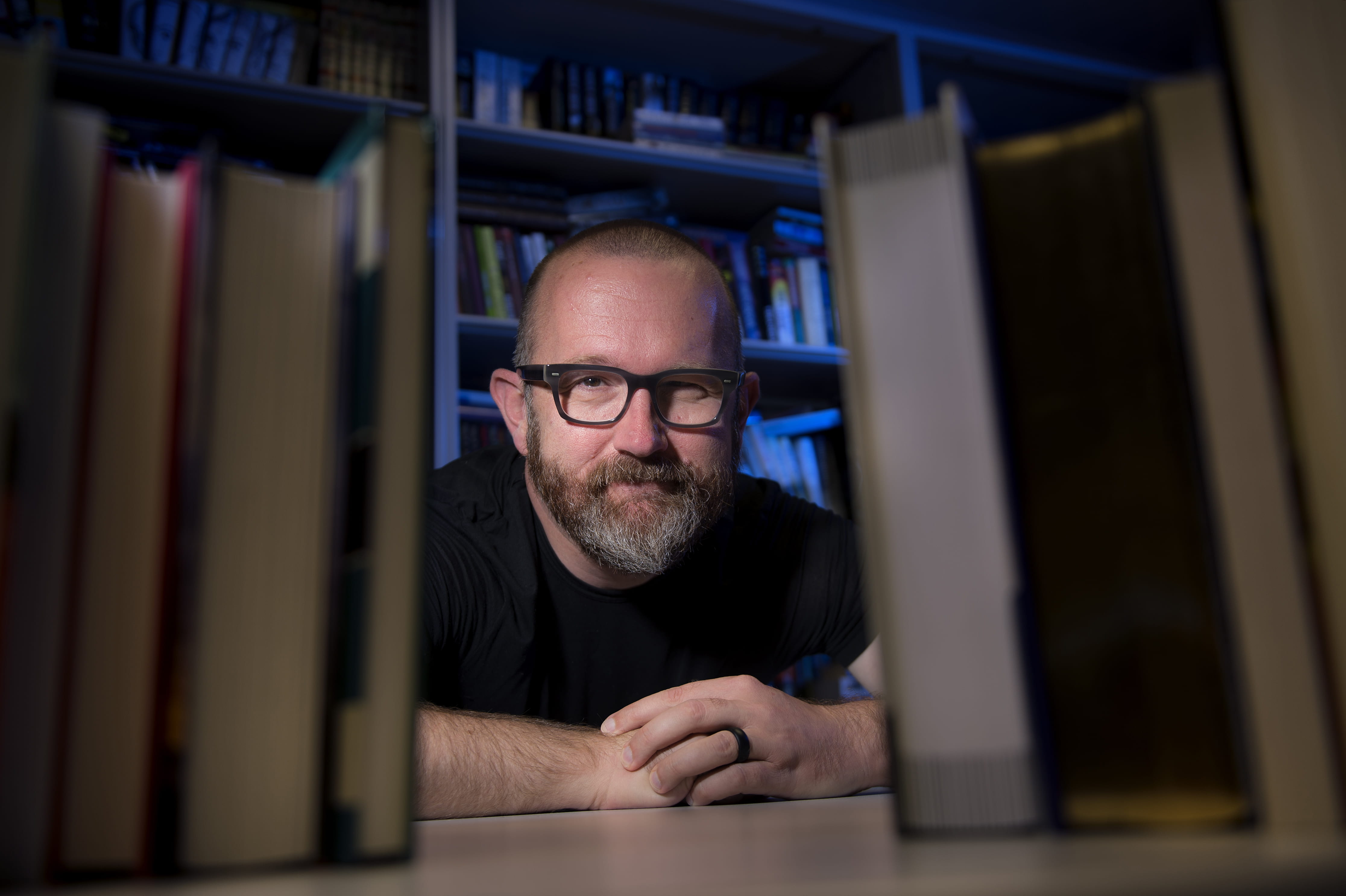

Pop lit protagonist

English professor who studies the genre believes young adult fiction has come of age

Jonathan Alexander first took an interest in young adult fiction – like millions of others over the past two decades – through J.K. Rowling’s ubiquitous Harry Potter series. However, his appreciation of the wizarding world came later than most.

“I really didn’t care for the books when I first read them in the late ’90s. I didn’t think they’d be much to pay attention to,” says Alexander in his Krieger Hall office, amid teetering stacks of vibrant paperbacks. “I guess I was wrong about that one, but I’ve been trying to make up for it ever since.”

The Chancellor’s Professor of English at UCI is a leading expert in the genre and editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books’ young adult section. But he didn’t realize the magnitude of YA fiction until he attended a Harry Potter book release party in the mid-2000s. Surrounded by hundreds of adolescents sporting wizard robes, Alexander was stunned by the unprecedented international fervor the novels had created. It was the perfect study for his field, the impact of literacy on beginning readers.

“Young adult books were getting larger and longer, and people were reading them for pleasure – absolutely loving them. There was an explosion in the genre,” he says. “I couldn’t help but try to figure out what effect YA fiction was having on people’s lives, and for the past decade, that’s what I’ve been doing.”

Alexander, who earned a Ph.D. in comparative literature at Louisiana State University, has read hundreds of YA novels over the years, ranging from cultural phenomena – Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders – to more obscure titles, such as the moving but somewhat neglected First Day on Earth, by Cecil Castellucci. Rather than studying the books themselves, he focuses on the influence these stories have on young readers and their experience of literacy.

Recently, he has delved into the world of fan fiction: enthusiast-made spinoffs based on popular YA fiction in the form of short stories, novels, graphic art, and YouTube videos that vary from short clips to full-length films.

“Most of it is genuinely good content. Kids are extending story arcs, inventing new characters, and introducing issues that are important for them to explore but that weren’t touched on in the books,” Alexander says, citing a work of Harry Potter fan fiction in which a Hogwarts student has autism and a Hunger Games offshoot that features characters using their Christian faith to survive in the arena.

“Fan fiction provides a means of delving into difficult topics like racism, sexism, homophobia, spirituality, disability – all of these things that are hard for kids to talk about but easier to project onto familiar characters and discuss that way.”

He examines these ideas in the latest of his 13 books, Writing Youth: Young Adult Fiction as Literacy Sponsorship. Among other subjects, he covers queer characters in YA literature, representations of standardized educational testing in dystopian fiction and the genre’s response to Hurricane Katrina, the 2005 natural disaster that hit his home city of New Orleans.

Alexander, who’s also a professor of education and gender & sexuality studies at UCI, stresses the emerging importance of popular literature in academia, where it was once ignored by scholars in favor of canonical classics. Studies of YA fiction, fantasy and science fiction are crucial to understanding culture, he says, because “they address serious topics and, to be frank, are read by a much larger portion of the population than Dickens and Dostoyevsky.”

He’s a fan of Sherman Alexie’s YA book The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian and Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus, which both present heavy subjects – poverty in Native American communities and the Holocaust, respectively – in formats more easily accessible than traditional tomes.

“The topics covered in these books are often extremely complicated and sophisticated, and authors use the popularity of the YA genre to disseminate their ideas to a wider audience,” Alexander says. “You can’t dismiss something as nonacademic just because of its form or because it’s directed at a certain demographic.”

His fascination with popular literature dates back to middle school, when the self-proclaimed “sci-fi nerd” first read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia and Frank Herbert’s Dune – “still one of my favorite books,” he notes. But he never imagined making a career out of this interest until he took a class on female authors while attending university in the 1980s.

“That opened me up to the incredible range of writing in our world,” Alexander says. “The prescribed canon on what kind of writing was worthy of study was just beginning to crack, and I decided to become an expert on those margins, since most weren’t doing it yet.”

Exploring YA literature has given him an acute understanding of the rising generation, which he calls a “dynamic social force.” Young adults, he says, are concerned about their futures, which is influencing current trends of dystopian and realist fiction featuring ecologically and economically precarious landscapes.

“The idea of finding careers and starting families – that goal of stability and happiness – is more tenuous now,” Alexander says. But today’s youth are also activists, he notes, and literature that appeals to them is imbued with a sense of purpose and optimism.

“It’s a heartbreaking mix of fear and adversity, along with hope and ambition and versatility, that makes this genre so worthwhile to me,” he says. “The stories I read are always challenging, but young people tend to come out triumphant in the end.”