Out of the shadows

UCI faculty bring hidden figures into the light for Black History Month

The Oscar-nominated film “Hidden Figures” tells the compelling true story of the African American women who were vital to the success of NASA’s launch of John Glenn into orbit but who – until now – were kept out of history books and the spotlight.

“The film reveals a greater truth: Throughout history, due to either gender or race (and often both), people who have made history are often left out of it due to social and institutional prejudices,” says Douglas Haynes, vice provost for academic equity, diversity & inclusion and professor of history.

In celebration of Black History Month, we asked UCI faculty to nominate black pioneers they think should be included in history books. They brought to light the following hidden figures.

Music

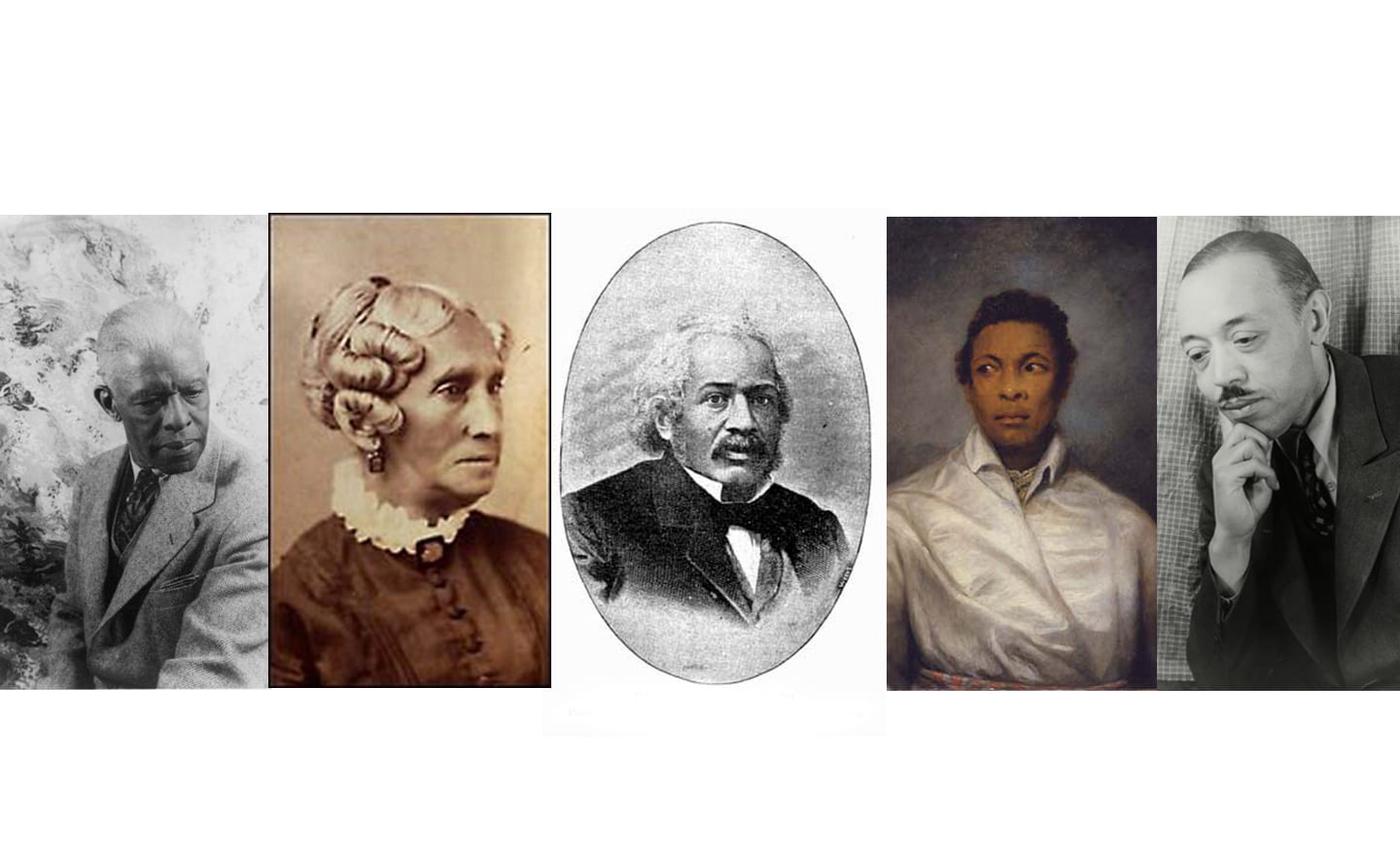

“Where does one begin?” asks music professor Darryl Taylor. “There are so many such stories. Let’s begin with William Grant Still [1895-1978], a great composer who dared to write symphonies and operas in the 1920s until his death in 1978. Without commissions, he wrote nine grand operas and five symphonies and music for ballets, films and television, as well as art songs and chamber music.”

Still was known as “the dean of African American composers.” One of his most popular works – Symphony No. 2 in G minor, “Song of a New Race” – was written in 1936-37 and was first performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski on Dec. 10, 1937.

“Florence Price [1887-1953] was the first black woman to have a symphony she’d composed performed by a major orchestra,” Taylor says. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frederick Stock, premiered Symphony No. 1 in E minor on June 15, 1933.

Roland Hayes (1887-1977) was one of the first male international singing stars of African American heritage. Taylor says that as a young tenor, Hayes would sing for silent films in Louisville, Kentucky, but would be sequestered behind a screen to hide his race from the white audience. “He eventually was to sing for royalty and in the best concert halls around the world,” Taylor says. “He’s considered a hero among black singers but remains relatively unknown to the general public.”

Hayes toured Europe extensively, performing in capital cities across the continent, singing in seven different languages. While in London, he gave a command performance at Buckingham Palace for King George V and Queen Mary. Although he never sang in an opera, he did record “Vesti la giubba” from the Italian opera “Pagliacci.”

George Walker, 94, lives in Washington, D.C., and is the first African American composer to receive a Pulitzer Prize for music. He won in 1996 – by a unanimous vote, no less – for “Lilacs,” for voice and orchestra. “The work is being performed by the UCI Symphony Orchestra during the opening concert of the African American Art Song Alliance Conference on Feb. 9,” Taylor says.

“Cecil Taylor is a contemporary composer, pianist and poet,” says Nahum Dimitri Chandler, UCI professor of African American studies and comparative literature and a co-principal investigator of the UC Consortium for Black Studies in California. “I’m a scholar of his work, but he has also become a friend and a mentor, in a sense.”

The New England Conservatory, of which Taylor is an alumnus, honored him with a doctorate in 1977. A recipient of Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships, Taylor was awarded the 2013 Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy, which included 50 million yen (roughly $500,000). In April 2016, the Whitney Museum of American Art held a retrospective on the 87-year-old’s art, music and life.

Medicine

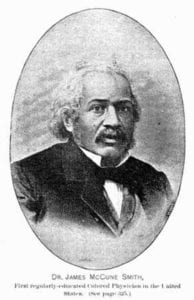

James McCune Smith (1813-1865) was a “brilliant, pioneering medical doctor, public intellectual and writer in the 19th century,” Chandler says. “A graduate of the legendary African Free School in New York City, fluent in several languages – ancient and modern – he was the first African American to earn a medical degree (at the University of Glasgow in Scotland), the first to publish in American medical journals, and perhaps the first to run a pharmacy in the U.S.” Yet Smith is largely known as a prominent abolitionist leader. With Frederick Douglass, he helped found the National Council of Colored People, the first national organization for African Americans, in 1853.

Highly educated women

“Ruth Ella Moore [1903-1994] was the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in the natural sciences,” Haynes says. “She earned her degree in bacteriology from The Ohio State University in 1933. Of the 381 known Ph.D.s awarded to African Americans through 1943, only 48 were earned by women. Among these recipients were some of the earliest women to receive degrees in the natural and behavioral sciences.”

Below are a few other African American women who were the first to earn Ph.D.s in their fields:

Flemmie Kittrell (1904-1980) received a doctorate in nutrition from Cornell University in 1935.

Marie Maynard Daly (1921-2003) earned a doctorate in chemistry at Columbia University in 1948.

Dolores Cooper Shockley, 86, received a doctorate in pharmacology from Purdue University in 1955, making her the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. there.

“Despite stunted career horizons that arose for no other reason than race – and, in some cases, gender and race – these pioneers challenged an entire social system that was organized to marginalize them at best and subordinate them at worst,” Haynes says.

Women’s rights

“The great women’s rights and African American liberationist lecturer of the 19th century, Maria W. Stewart [~1803-1879], was one of the first to leave copies of her speeches,” Chandler says.

Theater and dance

“I personally discovered Ira Aldridge [1807-1867], the talented 19th century tragedian, about a decade ago and have come to admire him greatly,” Chandler says. “He was a fabulous Shakespearean actor and has a special mark honoring him at Stratford-on-Avon.”

Aida Overton Walker (1880-1914) was a vaudeville performer, actress, singer, dancer and choreographer. “Despite being a celebrated star – an originator of the American genre of art-dance, a developer of modern dance, and a teacher-mentor who sought to better working conditions and expand roles for black women on the stage – Aida Overton Walker is no longer a household name,” says Jeanne Scheper, associate professor of gender & sexuality studies. “Bringing her into the forefront of discussions about race in the early 20th century might help us better contextualize the history of performance as critique, especially as it pertains to racial injustice.”

UCI-hosted events in celebration of Black History Month include the 20th anniversary African American Art Song Alliance Conference and the Workshop on Science, Technology & Race.