Global reach

UCI is sustaining its outsized reputation for tracking and tackling environmental challenges

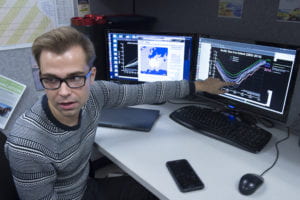

Each morning by 8 and again at night, UCI doctoral student Zachary Labe pushes a button, and the latest satellite data on Arctic sea ice unfurls on his computer screen. If it’s anomalous – that’s the scientific term for not normal – he plots it on a brightly colored custom graph and tweets it out to nearly 7,000 followers.

This winter has been full of anomalies: One week in November – when marine ice usually grows by leaps and bounds – saw a loss of 19,000 square miles, 10 times the size of the Grand Canyon. Days before Christmas, the North Pole neared the melting point, with temperatures 50 degrees above average. The deviations are part of disturbing long-term trends leaving polar bears stranded and sending warmer ocean waters lapping up against Greenland glaciers, ushering in sea level rise from Miami to California.

Labe, 24, who’s become a Twitter phenomenon thanks to his easily understood visuals, is in UCI’s top-ranked Earth system science department – the first in the nation when it was founded to study the planet and its interlocking pieces on a human time scale.

“The way I see it, why should I do this science if I can’t better explain and share it with the public?” says Labe, who wrote his own algorithms for the data. “Climate change is already affecting everyone, even if they don’t realize it, and this is a perfect opportunity to communicate the science.”

UCI has a storied, Nobel Prize-winning history of identifying critical climate challenges and pushing to solve them. The campus is moving ahead aggressively with both tracing the causes of global environmental change and exploring ways to cope with its effects, from more severe flooding and prolonged drought to changing refugee patterns and wildlife extinction. Tactics include hiring high-impact faculty in food and water security, innovative interdisciplinary research, new courses and community outreach.

“We are poised to continue major contributions to our understanding of sustainability issues and enable our society to find effective solutions to problems as they arise and evolve,” says Vice Chancellor for Research Pramod Khargonekar, an electrical engineer working in alternative energy who came to UCI last fall after heading the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Engineering. “We excel in multidisciplinary research that brings together experts from across the fields of science, engineering, law, social sciences and the humanities and beyond.”

“Our faculty has always tackled the big problems and not stayed in their silos,” agrees ecology and evolutionary biologist Travis Huxman, who is also faculty sustainability director. “It’s in our DNA.”

In the 1980s, founding professor F. Sherwood Rowland discovered that chlorofluorocarbons – used in spray deodorants and other aerosol products – threatened to rip a hole in the Earth’s ozone layer. Like Labe and his social media efforts today, Rowland persuaded New Yorker magazine cartoonists and others to illustrate the potentially devastating consequences of an ozone hole, namely widespread cancers.

The Montreal Protocol, considered the world’s most successful environmental treaty, resulted directly from his work. Rowland won the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry after being pilloried for years by industry leaders. This April, the American Chemical Society plans to designate as a national landmark the physical sciences building at UCI that bears his name.

“We learned the critical lesson from him that you don’t just do science; you walk it all the way through to policy,” says Huxman, who heads the campus’s Center for Environmental Biology.

“Sherry was criticized, threatened, and he was just a world-class citizen. His work was instrumental in society making global progress after we gained knowledge of our potential destruction,” says law and social ecology professor Joseph DiMento, former longtime director of the Newkirk Center for Science & Society. “And he did it here at UCI.”

Today, the university offers nearly 150 classes and several majors and minors related to sustainability – from environmental anthropology to industrial toxicology – and its climate work stretches across campus and the planet.

“I’m so proud to be part of this institution,” says Kristina Shull, a history lecturer who will teach a new course this quarter on people displaced by climate change. Humanities and science students will examine several case studies, including Mali weather refugees in U.S. detention centers, Marshall Island migrants whose homes were harmed by nuclear testing and who are now watching their nation sink into the ocean, and immigrants dying in greater numbers on the U.S.-Mexico border because of drought and heat.

“We’re taking the two hairiest debates of our time – climate change and immigration – and exploring the connections,” she says. “These are two very important issues that are confronting us right now. I hope students can avail themselves of the resources on campus and see how history is actionable.”

One area in which UCI is globally recognized is its polar work. Glaciologists Eric Rignot and Isabella Velicogna and their teams used satellite data to identify the irreversible collapse of West Antarctica and an ice trawler to map Greenland’s accelerating melt rate. Climate and computer scientists track the relationships among Earth’s massive ice sheets, the seas and the skies above.

“What’s happening in the Arctic is just astounding; it’s twice the rate of temperature increase compared to anywhere else in the world,” says Gudrun Magnusdottir, chair and professor of Earth system science. She and fellow researchers have found that the loss of thick blankets of sea ice “lifts the lid off the warmer ocean and releases all these energy fluxes” that heat the air and melt glaciers.

Closer to home, Huxman and environmental law professor Alejandro Camacho, director of the Center for Land, Environment & Natural Resources, help area land managers – from park rangers to would-be developers – understand the costs and benefits of habitat conservation and how and if plant and animal species should be relocated outside their typical ranges as the climate warms. Environmental Law Clinic students, led by law professor Michael Robinson-Dorn, assist communities grappling with rising ocean waters, oil and gas fracking, and other legal challenges.

“If one wants to affect the course of human activity and how it affects the natural world, then the most direct way is through the law,” Camacho says.

The campus also “walks the talk,” sharply reducing its own carbon emissions footprint, says Associate Chancellor for Sustainability Wendell Brase. It is the first in the nation to procure an all-electric student bus fleet and has twice been voted the Sierra Club’s “Coolest School.” UCI engineers working with Edison International and Southern California Gas Co. have used faculty homes and the campus power grid to test low-carbon energy. Preserves provide habitat for endangered species.

Biology professor Steve Allison heads a cross-campus Climate Action Training Program that resumes this month to teach students about the thorny issues involved in climate change and sustainability and how to apply that knowledge in varied careers. Ten master’s and doctoral students in ecology, history, chemistry, biology and engineering will participate.

“They learn to communicate difficult concepts, like uncertainty,” Allison says. “There’s not much doubt climate change is occurring. The uncertainty is in the consequences – how fast, when and where those changes will occur. One of the main goals is to think about solutions at the local scale.”

The first group last fall took a law class taught by DiMento and scientists from across campus and dissected the policy section of the latest United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, of which UCI atmospheric chemist Michael Prather has been a lead author for decades. They interned with a Newport Beach nature center, the KPCC radio station, and water and transportation agencies.

“I’m very proud of what the students accomplished. It wasn’t easy,” Allison says.

DiMento says of the interdisciplinary law class: “Increasingly, scientists are learning that they can’t sit above it all as the world goes to hell in a handbasket. On the other side, our law students were immensely impressed by the quality of climate science research here.”

Mark Newman, who’s earning his master’s degree in urban planning, says he learned not to be afraid to ask questions about complicated or controversial topics. Via paid internships with the California Department of Transportation, the Orange County Transportation Authority and the city of Santa Ana, he focused on long-term, sustainable transportation planning, including pleasant, obstruction-free sidewalks and sensible bicycle lanes linking schools, homes and stores.

“People in Southern California live far from their jobs, and they sit in their cars on the 405 and 5 freeways, generating lots of greenhouse gas emissions,” notes Newman, who drives a Prius and walks whenever possible. “I do feel like an extreme oddball walking along a major road, and I’m the only pedestrian, but how else are we going to do it?”

He and fellow trainees say the program opened their eyes not just to the global specter of climate change and societal upheaval, but to new career options and the wide variety of campus programs. Previously, Newman had no idea that game-changing hydrogen fuel cells for transportation – his chosen field – had been developed here.

“This needs to be taken seriously,” he says. “We need widespread implementation of alternative energy forms in our automobiles and our industries. The technology is there; we just need to stay the course.”