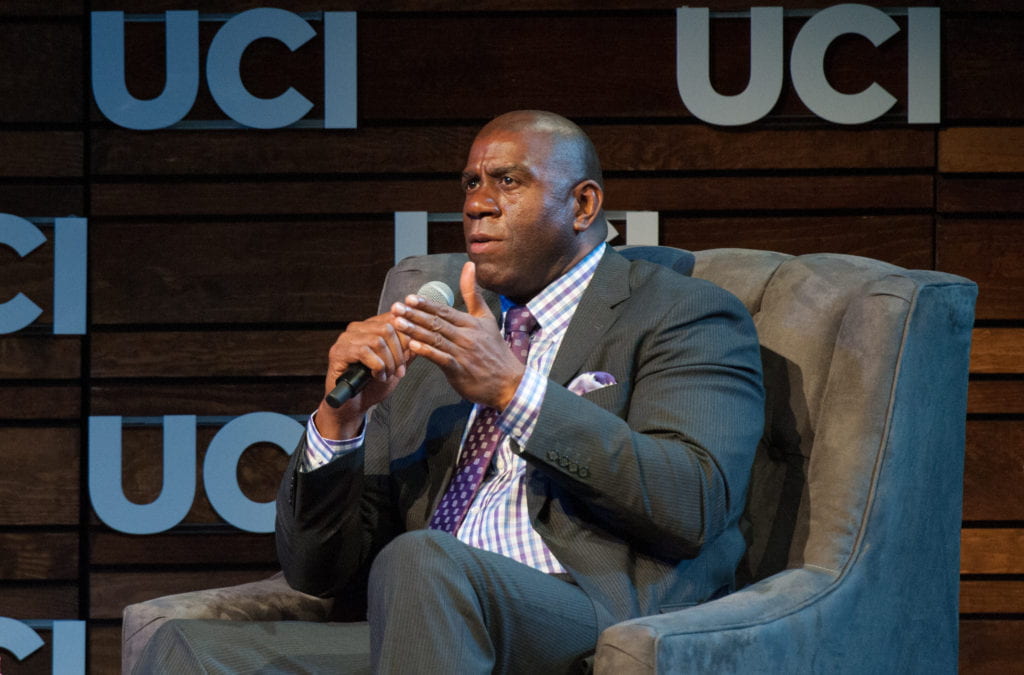

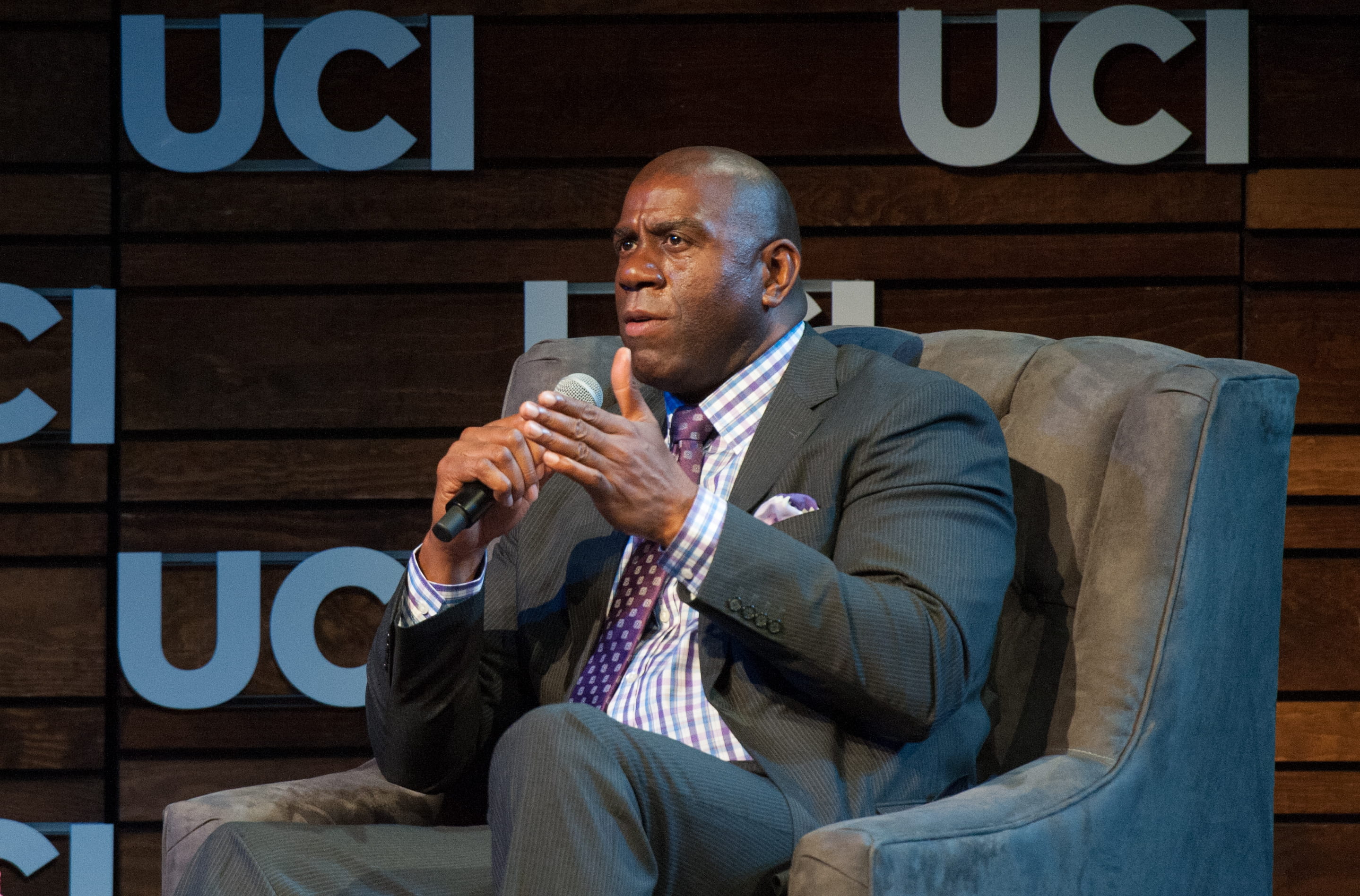

A Magic moment

Basketball legend Earvin Johnson opens the 2015 Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellows Series

On Monday, May 11, at the Irvine Barclay Theatre, a big man sat in an oversized chair and talked about grand ideas for improving the world through jobs, education and economic investment in urban minority communities.

And then he treated the sold-out crowd to a little nostalgic role-playing, dribbling an imaginary basketball down the court and passing off to a Los Angeles Lakers teammate who executed a signature skyhook for an elegant 2 points.

Earvin “Magic” Johnson Jr., the opening speaker in UC Irvine’s 2015 Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellows Series, blended his experiences in basketball, business and philanthropy into an hourlong conversation with Valerie Jenness, dean of the School of Social Ecology.

Launched in 1999 by then-Chancellor Ralph Cicerone, the lecture series brings to campus eminent scholars and public figures who are active change-makers and leaders in today’s increasingly interdependent world.

Johnson illustrated how strong family values, a competitive spirit and a college education laid the foundation for his transformation into one of the most successful African American businessmen in the U.S. – and how that combination can fuel others’ success.

“If you look at me as just a basketball player, you’ll be missing a business opportunity,” he’s fond of saying.

Johnson’s storied career in basketball includes five NBA championships, three NBA MVP awards, nine NBA finals appearances and 12 All-Star Games. He still holds the NBA record for average assists per game. He was named one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history in 1996 and is one of only seven players to win an NCAA championship, an NBA championship and an Olympic gold medal. His number – 32 – was retired by the Lakers.

In 1991, Johnson announced that he had contracted the AIDS virus. Early detection, rigorous adherence to a drug regimen, and the support of his wife, Cookie, saved his life, he said, and he eventually retired from basketball to commit himself to new pursuits: AIDS activism and giving back to his community.

Johnson set out to find companies willing to open outlets in urban neighborhoods. The goals were to improve local services and health and to provide jobs.

“I knew there was buying power in the minority communities ¬– $1 trillion in black America and $1 trillion in Latino America,” he said. “Everyone wanted to take a meeting with me, but nobody wanted to invest.”

Finally, Starbucks said yes. Before he sold them, Johnson had more than 100 of the coffee franchises in inner cities.

“People were asking me, ‘Will black people pay $3 for a cup of coffee?’ Sure we will,” he said. “We don’t quite know what scones are, though.”

Today, Magic Johnson Enterprises fosters neighborhood and economic empowerment by providing access to high-quality entertainment, products and services that meet the demands of multicultural communities. And although it’s become easier to convince major retailers to invest in such areas, Johnson said, it’s still his biggest challenge – especially when some of the businesses he’s worked hard to bring in are vandalized or burned.

“People want their voices heard, and then they want some action,” he said of residents in Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore and other cities recently in the news. “They don’t want to see their people killed, but burning down a CVS is not the answer. I was on the front line fighting for businesses to come in there. And is that business coming back? Probably not. And now where is Mom or Grandma going to get prescriptions?”

Workshops are needed to bring together police and residents, Johnson said, and education is critical.

“What’s going to happen after CNN leaves?” he asked. “We need to educate those young people. We need to build centers for job training.”

The Magic Johnson Foundation is tackling those issues. It has funded 10,000 student scholarships and 20 technology centers in which youths who can’t afford home computers can complete their schoolwork. Earlier in the day, their parents and grandparents use the centers to learn and improve job skills.

The foundation also sponsors employment and health fairs in underserved communities. Medical vans provide physicals, vaccinations, dental work and other services needed to help children succeed academically. “Drop-back-in centers” have inspired young people to return to high school and even college – not easy or comfortable for many who are first in their families to seek a university degree.

“My parents never finished high school,” Johnson said, “but they stressed education, and I owe a lot to them. My father had a work ethic that was off the chart. My mother was always giving back to the community – to people she didn’t even know.”

He and many of his nine siblings attended college. “We were poor,” Johnson said, “but we never had poor dreams.”