Looking back into the future

UC Irvine physics professor and award-winning science fiction author Gregory Benford will write the introductory essays for “The Wonderful Future That Never Was,” a collection of predictions made in the pages of “Popular Mechanics” that reflects societies hopes and fears.

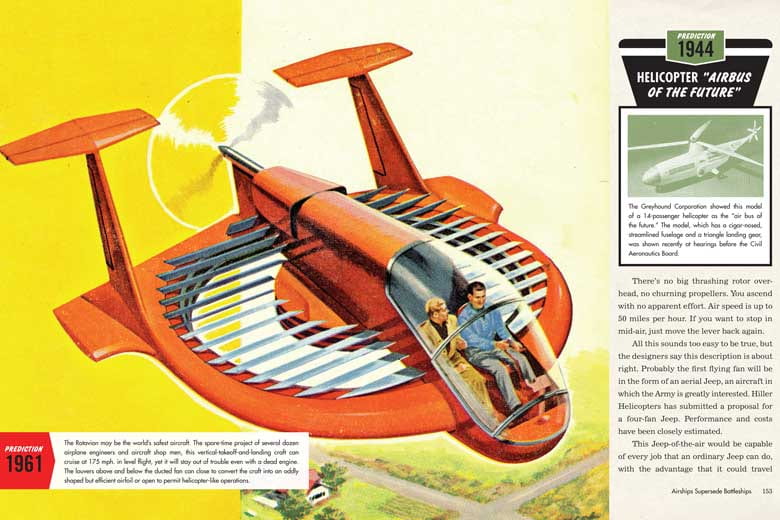

Waterproof houses that can be washed down inside with a hose. Personal commuter helicopters. Massive, odorless cities with elevated moving sidewalks. Colonization of the solar system.

All these ideas, and more, appeared in the pages of Popular Mechanics magazine between 1903 and 1969, when scientists and other experts made hundreds of predictions of what the future would hold. Most didn’t happen; others, such as video phones, supermarket frozen foods and global positioning systems did.

Popular Mechanics editors collected these predictions in a book The Wonderful Future That Never Was, and asked UC Irvine physics professor and award-winning science fiction author Gregory Benford to write the introductory essays. As with science fiction, the predictions not only point to the future, they reveal much of society’s mood at the time. Whimsical in places, The Wonderful Future offers a bracing history of our hopes and fears, and the boundless optimism of the human spirit.

Benford sat down with Jonathan Alexander, UCI Chancellor’s Fellow, professor of English and a science fiction scholar, to discuss the The Wonderful Future and the relationship between science fiction and 20th century society.

Q: What are your impressions of The Wonderful Future That Never Was?

GB: It struck me that much of book, as with science fiction, is about transport, travel and getting away — often getting away from the past. It’s the idea of liberation by movement, which is a very American idea.

JA: That makes a tremendous amount of sense, particularly the idea of movement as liberation. The further we got into the 20th century, the more society was thinking expansively about travel, about “leaving the farm.” You have this massive mobilization of people from the countryside into urban areas, and that movement can be tracked with how we imaged future technologies and urban areas during the 1930s and ’40s.

GB: Just as it was inevitable that Americans would be fascinated with transport and would go to the moon, they also pioneered home-based technologies, and in The Wonderful Future there are images of people at home talking to people they can see on-screen in other continents — just as we do now on Skype. One striking thing this book and science fiction didn’t see is that so much interconnectivity is free right now. They always thought it would follow a commercial model.

JA: While the book imagines the centrality of travel and of bridging distances, it doesn’t fully imagine the revolution in communications that has occurred, which is so key in our increasingly “globalized” world. I don’t know if people could have envisioned that. In some ways, this ability to telecommunicate has replaced our need to travel, to bridge distances. Subsequently, there has been a decline in the effort to explore or colonize the solar system. It seems more pressing in mid-century science fiction and less a part of it now.

GB: Manned space travel turned out to be harder than we thought and has essentially ceased.

JA: But we can send our devices to those places, and they can beam back amazing images and amazing amounts of data.

GB: You’re right, and that’s a thing Popular Mechanics and science fiction didn’t anticipate — that the true utility of unmanned space travel would dominate exploration.

Q: The book’s content covers the first seven decades of the 20th century. How did predictions reflect the mood of the times?

GB: Strikingly, in the 1930s, during the heart of the Depression, science fiction and Popular Mechanics predictions were very optimistic, just as ’30s movies were full of rich people doing dances. And just as strikingly, science fiction, beginning around 1970, started to become more and more dystopian, to paint worlds in which societies did not work and were oppressive, such as the movie Blade Runner.

JA: The really interesting thing about science fiction is that sometimes it’s about the future but mostly about the present in which it was actually written. I’m thinking particularly about the mid-1950s movie Forbidden Planet, in which we hear about this ancient civilization, the Krell, who created a massive technological apparatus that freed them to do other things, like create art and engage in self-development. That kind of emphasis on labor-saving devices was common thematically in science fiction at the time, and The Wonderful Future shows it well. You see technology as labor-saving, as freeing people — not just letting them get off the farm but also allowing them fuller explorations of their lives. Curiously, the Krell became extinct because of their technology. What allowed them to save time, to explore themselves, ultimately led to self-destruction. In the 20th century, we created all these labor-saving devices, but we also have intercontinental ballistic missiles. So, our imagination of science and technology by mid-century becomes double-edged.

Q: How has science fiction teamed with science and technology to create this vision of the future? Do art and science walk hand in hand?

GB: It’s more like a dance. In a 1912 novel, H.G. Wells anticipated nuclear weapons, which influenced physicist Leo Szilard to come up with the idea of the nuclear chain reaction in 1933. The point is that the central idea was inspired by a science fiction novel, and it makes you wonder how different the world would be if Szilard hadn’t read that book, because he was the driver in the U.S. for the nuclear weapons program.

JA: There are many instances like this. Arthur C. Clarke imagined satellites before any were created. Many scientists say that science fiction inspired them to pursue science.

GB: Like reading Popular Mechanics did for me! Modern science fiction is the expression of the technological-scientific class in world literature, because this was not being expressed by the literary community. It’s no accident that many science fiction writers, especially in the early pulp magazines, were engineers and scientists.

JA: Most recently, though, we see the emergence of slipstream literature, where important literary authors like Michael Chabon and Richard Powers borrow from science fiction to grapple with important questions of technology and science and what it means to be human. This represents a profound recognition among literary authors that technology is so suffused into society. We are cyborgs in significant ways. We need to be reflecting on what this means for our humanity.

Q: What would this book include if it came out 50 years from now?

GB: The thing that will dominate world affairs is when we actually and finally, both politically and technically, realize that we are stewards of the earth, and if we don’t take care of our planet, we will perish. That’s going to be the major agenda of the century, which will be clear 50 years from now.

JA: I think that’s right, and there are some very good science fiction writers who have talked about the need to think about the planet more carefully, such as Ursula K. LeGuin. Additionally, lots of science fiction today is about artificial intelligence and the cyborgization of our own bodies, as we see in cyberpunk science fiction. I think that our own interconnectivity with technology will continue to fascinate authors. As for artificial intelligence? Eh, I don’t know. Robotics? Absolutely. Also, this book 50 years from now will predict things that probably won’t come true. Star Trek for instance gives us lots of ideas, but I don’t think we’re going to reach warp drive.