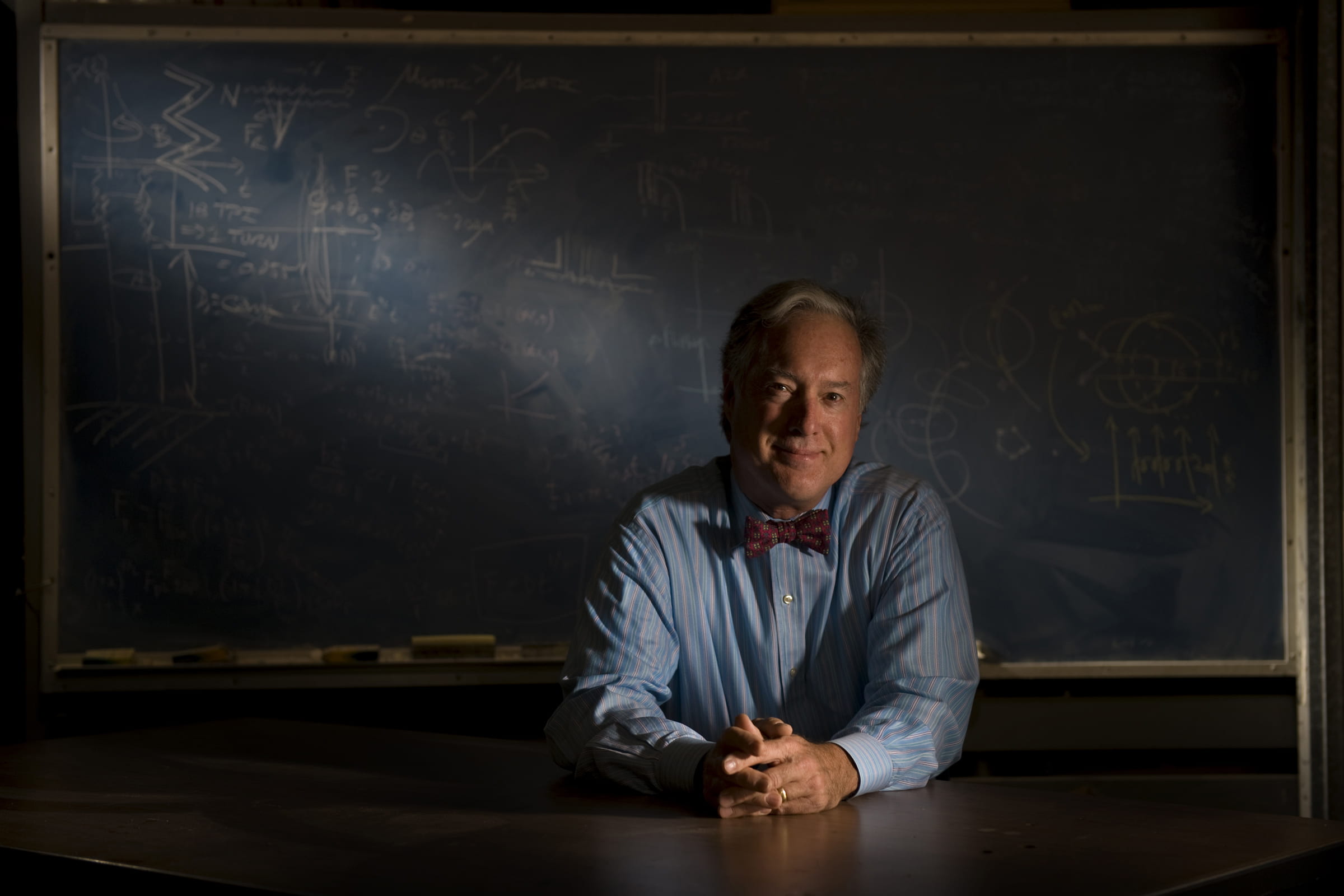

Old-fashioned physicist invents futuristic tools

With his bow ties and seersucker suits, Roger McWilliams might appear to be old-fashioned, but the UCI physicist invents futuristic laser tools that have advanced everything from telecommunications to healthcare.

UC Irvine physics & astronomy professor Roger

McWilliams often appears to have stepped out of a time machine — from

the past. He rides to work on a reproduction vintage bicycle with a

wide leather seat and big chrome handlebars. When he does drive a car,

it’s a 60-year-old Jaguar that he fixes himself with his collection of

antique tools.

In May, when the UCI Alumni Association presented McWilliams with its

Lauds & Laurels

faculty achievement award, he showed up in his trademark bow tie and a

seersucker suit. “Bow ties are just one of the things I like, and I

don’t mind if they fit in or not,” he says.

At the Anthill Pub & Grille, where he frequently plays the saxophone with other faculty members in the

Interactions Jazz Ensemble,

McWilliams looks more like a character from “The Music Man” than a university professor.

But

while he strikes many as old-fashioned, he creates laser-based devices

like something out of the future. Many of them generate plasma —

“matter so hot it’s ionized” and the subject of his 30-year career at

UCI. McWilliams has a bow tie depicting a prime example of plasma: the

sun.

“Since much of the known matter in the universe is plasma, there’s

more than enough to spend decades studying,” he says. “I’m always

looking for new ways of doing things with plasma.”

While

they sound like the stuff of sci-fi, his devices have practical uses in

healthcare, telecommunications and other fields. “The invention of new

tools often leads to new physics. I focus on those that have social

utility,” he says. “In science, it’s nice to contribute to an area that

helps other people.”

Dr. Roger Steinert,

an ophthalmologist at UC Irvine Medical Center, says McWilliams has

helped develop the instruments for his pioneering advances in laser eye

surgery.

“Lasers that create plasma now are workhorses in treating eye

disorders. They can act like a clean scalpel, generating minimal heat

or collateral damage, while reaching inside the eye with no incision,”

Steinert says. “His work has greatly affected my own for nearly three

decades.”

McWilliams’

plasmas and lasers range in diameter from one-tenth of a human hair to

the fuselage of a 747. “Here’s an electrosurgery tool for taking

tonsils out,” he says, showing off a handheld device that looks like a

fountain pen. “Instead of a knife, it’s a plasma blade about the

thickness of a human hair. A surgeon can cut and cauterize at the same

time. It helps with healing.”

He works in a lab similar to Doc’s garage in “Back to the Future,”

filling the basement of Frederick Reines Hall with a hodgepodge of old

office furniture, books, occasional car parts, bikes, pumps, fans,

coils and other equipment. All that’s missing is a time-traveling flux

capacitor.

“People find me quirky — I don’t know why,” McWilliams says. “Maybe it’s because my interests cross many borders.”

Indeed, although he’s a scientist (getting a bachelor’s in physical

sciences from UCI in 1975, then earning a doctorate in plasma physics

at Princeton University in 1980), he taught in UCI’s Humanities Core Course

for four years and peppers his conversation with references to everyone

from Plath to Proust. It’s the rare scientist who keeps the entire

Oxford English Dictionary in his lab, where he greets students from a

vintage desk piled high with papers, journals — and a spare car

distributor.

McWilliams, the founder and former director of the

Campuswide Honors Program

and founder of the

Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program,

isn’t much more orthodox in class: He encourages students to step away

from their textbooks and experiment on their own. His exams are

interactive.

One called for test-takers to tear off the bottom of the exam paper,

blow on the strip’s edge and calculate the oscillation. And it wasn’t

hard to tell when students reached this challenge: “Stand up and

estimate the spring constant of your shoes reacting to your standing

body.”

“Education

should have relevance to real life,” McWilliams says. “It’s not some

fuzzy-haired guy in a bow tie standing at a podium in a windowless

classroom.”

To

translate his own research into products and services with “social

utility,” he’s collaborated with national labs and businesses, working

with former students who’ve gone on to places like TowerJazz (formerly

Jazz Semiconductor) and Broadcom. He’s also helped companies develop

lasers that boost Internet signals carried by transoceanic fiber-optic

cable.

“Physics is about the world we live in,” McWilliams says, “and making it a better place.”