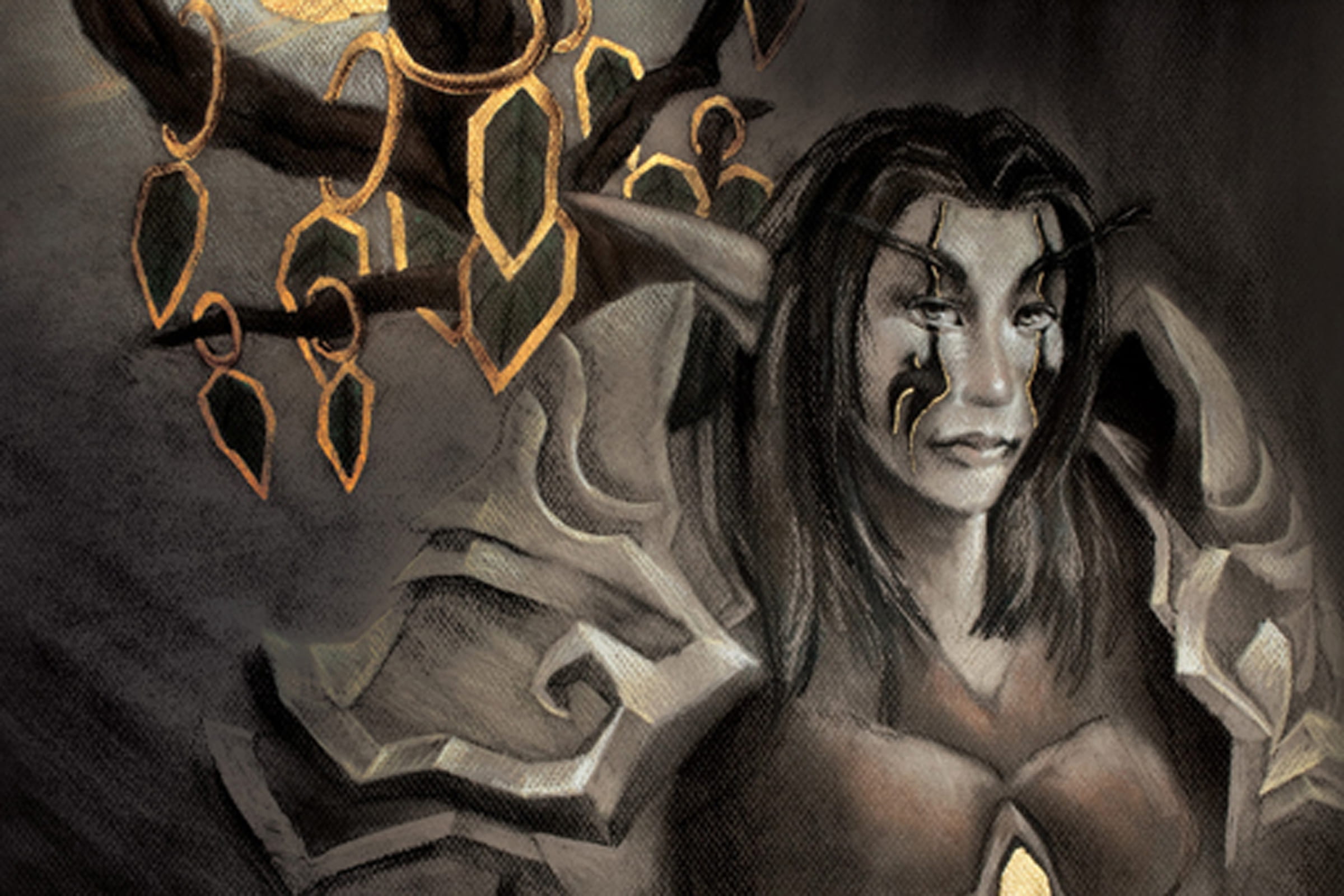

Going undercover as a Night Elf Priest

Bonnie Nardi shares findings from her participatory study of the online role-playing game World of Warcraft.

UC Irvine informatics professor Bonnie Nardi recently published My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of World of Warcraft. The book is based on her research of the massively multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft, which has amassed 11.5 million subscribers worldwide. Commonly known as WoW, the MMORPG is produced by Irvine-based Blizzard Entertainment.

Interested in computer-mediated communication and society and technology, Nardi studies gender roles, culture and addiction in the play experience. She has spent more than three years participating in WoW in the U.S. and China – as a Night Elf Priest.

Q: How has the online gaming community been transformed by MMORPGs like World of Warcraft?

A: WoW is proof that online video games can appeal to a wide variety of demographic groups beyond the first-person shooters, which are primarily the province of young men. WoW has a healthy number of female players – about 20 percent – and people of all ages. In my guild, or club, is a man with five grandchildren, a 16-year-old boy and everything in between.

Activities within the game are also unusually diverse. You can play by yourself or with others. You can engage in quests, which are short mini-games, or join in raids in which 10 to 25 players collaborate in difficult battles that may take weeks to win. Some people enjoy the economics in the game and play the Auction House. It’s up to the player. From a research point of view, the diversity is interesting but also a challenge, because it’s hard to generalize about 11.5 million players.

Q: How do online character interactions differ from face-to-face interactions?

A: In situations where people play with those they don’t know (some contests throw together ad hoc teams), individuals often behave badly under cover of anonymity – nerd rage. But frequently people play with real-life friends and family, and interactions are governed by standard rules of good conduct.

In between is an interesting twilight area in which you interact with people you know pretty well in-game, such as guild mates, but probably won’t ever meet in real life. Behaviors that would be inappropriate at school or work, such as sexualized and scatalogical talk or outrageous flirtation, are permissible and common. Players stretch the boundaries of conventional good taste, taking advantage of what play theorists call the “magic circle” that allows us to abandon certain rules of ordinary existence.

Q: What key differences did you observe between U.S. and Chinese players?

A: The most important finding from my research is that play in the U.S. and China is remarkably similar. Players in both countries like WoW graphics, the sociable experience it offers and the challenge of the contests. The game’s cross-cultural appeal demonstrates the power of software to shape human activity, a subject I go into in depth in my book.

However, there are some differences: In China, people often play in Internet cafes, or wang ba. A significant face-to-face component to game play is part of the experience, and it occurs in a public space. Sometimes people meet new people in wang ba, and sometimes they go with their friends. My very first interview in China was with a group of five young men who were playing WoW together and planned to go to dinner afterwards. If you see someone playing WoW and would like to sit next to him or her so you can talk about the game, you can ask another patron to change seats. Play combines the real and the virtual.

Another difference is the reluctance of Chinese males to play female characters. In the U.S., males often play female characters because they like the way they look. In China, such players are called “lady boys,” akin to transvestites – and that’s not a compliment. Female players in both countries nearly always play female characters. In China, they must sometimes explain that they are not “lady boys.” They seem to take this in good grace.

Q: Are these cultural differences?

A: The “lady boy” meme can be said to be cultural. In interviews, Chinese players reported that it’s “natural” for men and women to be different and that this difference should be respected. In this context, we can construe culture as representing habitual, persistent patterns of thought and activity.

But regarding wang ba – is that culture? Wang ba play produces a distinctive gaming experience, but people often play there because they don’t have a good computer at home or because they live in cramped quarters with their parents until marriage. Still, some players said they chose wang ba because they liked the social experience, so it’s complicated. Cultural difference is a notion to be approached cautiously; differences are often more a function of economic and political realities.

Q: Do you plan to continue as a Night Elf Priest in the upcoming Cataclysm expansion of WoW?

A: Yes. I have tried many types of characters, and priest is still my favorite. I enjoy healing because my actions affect the characters of other players, not just the game monsters. I have preview access to Cataclysm and have created the cutest goblin ever! She’s a shaman, which is like a sturdier priest. I continue to play in order to observe historical transformation in the game – in particular, issues of governance between Blizzard and the player community. WoW is a kind of mini-culture – one controlled in large part through software – with its own history and unique dynamics.