Neural stem cells offer potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease

UC Irvine scientists have shown for the first time that neural stem cells can rescue memory in mice with advanced Alzheimer’s disease, raising hopes of a potential treatment for the leading cause of elderly dementia that afflicts 5.3 million people in the U.S.

UC Irvine scientists have shown for the first time that neural stem cells can rescue memory in mice with advanced Alzheimer’s disease, raising hopes of a potential treatment for the leading cause of elderly dementia that afflicts 5.3 million people in the U.S.

Mice genetically engineered to have Alzheimer’s performed markedly better on memory tests a month after mouse neural stem cells were injected into their brains. The stem cells secreted a protein that created more neural connections, improving cognitive function.

“Essentially, the cells were producing fertilizer for the brain,” said Frank LaFerla, director of UCI’s Institute for Memory Impairments & Neurological Disorders, or UCI MIND, and co-author of the study, which appears online the week of July 20 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

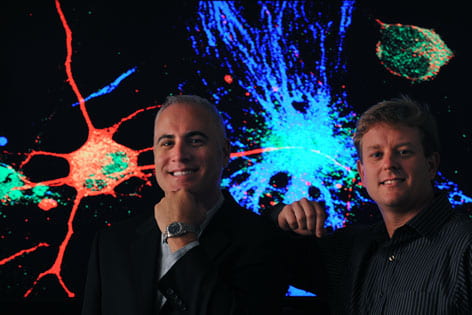

Lead author Mathew Blurton-Jones, LaFerla and colleagues worked with older mice predisposed to develop brains lesions called plaques and tangles that are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.

To learn how the stem cells worked, the scientists examined the mouse brains. To their surprise, they discovered that just 6 percent of the stem cells had turned into neurons. (The majority became the other two main types of brain cells, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.) The stem cells didn’t improve cognition by becoming new neurons, nor did they act by reducing the number of plaques and tangles.

Rather, the stem cells were found to have secreted a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. This caused existing tissue to sprout new neurites, strengthening and increasing the number of connections between neurons. When the team selectively reduced BDNF from the stem cells, the benefit was lost, providing strong evidence that BDNF is critical to the effect of stem cells on memory and neuronal function.

“If you look at Alzheimer’s, it’s not the plaques and tangles that correlate best with dementia; it’s the loss of synapses – connections between neurons,” Blurton-Jones said. “The neural stem cells were helping the brain form new synapses and nursing the injured neurons back to health.”

Diseased mice injected directly with BDNF also improved cognitively but not as much as with the neural stem cells, which provided a more long-term and consistent supply of the protein.

“This gives us a lot of hope that stem cells or a product from them, such as BDNF, will be a useful treatment for Alzheimer’s,” LaFerla said.

In April, LaFerla, Blurton-Jones and colleagues were awarded $3.6 million by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine toward the development of an Alzheimer’s therapy involving human neural stem cells.

In addition to LaFerla and Blurton-Jones, Masashi Kitazawa, Hilda Martinez-Coria, Nicholas Castello, Tritia Yamasaki, Wayne Poon and Kim Green of UCI worked on the study, along with Franz-Josef Muller and Jeanne Loring of the Scripps Research Institute. Funding for the study was provided by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the National Institutes of Health.