Defying gravity

Dr. Roger Walsh, professor, psychiatrist and philosopher, reflects on the uplifting power of meditation

Dr. Roger Walsh has always sought higher ground.

As a student at the University of Queensland, Australia, he earned degrees in psychology, physiology, neuroscience and medicine – while working as a circus acrobat. Fearless in the face of heights, he set world records for the trampoline and high dive (by plunging more than 100 feet off a bridge). By the time he came to the U.S. as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University in 1972, Walsh seemed to be firmly planted in the field of neuroscience. The former acrobat, however, soon saw his career swing in a radically new direction. He became an expert in Asian philosophies, meditation and other spiritual practices, both personally and professionally exploring the transcendent in human experience.

Walsh, now professor of psychiatry & human behavior and holding joint appointments in philosophy and anthropology at UCI, still has the lean, limber look of someone who could easily fly from a trapeze. Once a “hard-core skeptic” who put all of his faith in science, he turned to contemplative practices after he began training as a psychotherapist at Stanford and decided to try a little of his own medicine.

“I went into therapy because I didn’t have much faith that it really worked, and I wanted to see for myself,” he says. “A couple years later, I staggered out of there a very different person. It was perhaps the most transformative experience of my life.”

His therapist introduced him to meditation, and for the first time in his life, he began “looking inward.” So began Walsh’s 30-year odyssey of the mind. As he continued looking within, taking up meditation and other contemplative practices, he began to delve deeply into religious traditions and explore a variety of spiritual disciplines such as Eastern yoga and Western contemplation.

“I discovered inner worlds I had no idea existed,” he says. “These inner worlds proved to be rich reservoirs of unsuspected intuition, understanding and wisdom.”

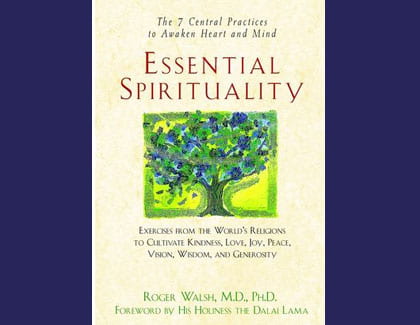

With interest in Eastern spiritual practices growing in the West, Walsh become a sought-after source of insight into contemporary spirituality. One of his books, Essential Spirituality: The Seven Central Practices to Awaken Heart and Mind, combines simple, practical exercises with wisdom culled from the world’s major religions to encourage spiritual growth; the Dalai Lama himself gave the book his blessing in the foreword.

Since coming to UCI in 1978, Walsh has been voted the psychiatry department’s Outstanding Teacher of the Year six times. He recently spoke at the Tibet-inspired Peace Flag Project organized by Dalai Lama Scholar Rebecca Westerman, and he serves as advisor to AUM, the Association of University Meditators.

“Since AUM’s inception in 2006, Dr. Walsh has been an amazing mentor for the club. He provides us with guidance and support on a group and individual level,” says last year’s AUM president Andrea Johnston ’08, who received her bachelor’s in psychology and social behavior. “He’s helped the club flourish, and he’s cultivated relationships with many of us individually to help us develop our own spirituality and purpose in life. The impact he has had on my life will be strong and lasting.”

Walsh says he’s encouraged by the growing interest in spiritual practices at UCI and beyond.

“When people meditate, there’s a paradoxical response. They turn their attention inward, but they also tend to become more sensitive to the suffering and well-being of others,” Walsh says. “AUM is deeply involved in community service. It’s a good example of what these practices can bring out in people.”

A Q&A WITH ROGER WALSH

What are reasons one should meditate?

Meditation offers a variety of benefits. For example, it cultivates awareness and sensitivity, as well as greater concentration, calm and equanimity – the capacity to remain calm and composed in the midst of turmoil. The purpose is to train the mind, and thereby foster psychological and spiritual well-being and growth. Eventually, meditation becomes a self-rewarding process. It’s similar to exercise. If you do it, you feel the benefits; if you don’t do it, you miss it.

How does one begin a meditation practice?

A daily routine really helps, as do a teacher and a support group of fellow meditators. You can start by practicing 15-20 minutes a day in a quiet, pleasant environment. There are many methods; one is to simply sit up straight and gently focus on the sensations of the breath to quiet the mind. Several kinds of meditation are described in Essential Spirituality.

At first, the mind is very difficult to work with. In the West, we spend our lives rushing around and looking outside, not within. Our culture promotes stimulation and stress – it’s designed to capture and hold our attention. So when we first turn our attention inward, the mind feels frantic and fragmented. The metaphor is that of a wild, drunken monkey – what the Buddhists call “monkey mind.”

Fortunately, as you progress with meditation practice, you gradually experience greater calm and peace.

What is your own meditation practice like?

I try to get in one to two hours a day. I find I’m a happier, calmer person that way, and so it’s naturally become a priority. If I don’t start the day with meditation, then the day just “goes.”

I start out meditating early in the morning, when my mind hasn’t gotten caught up in the day’s craziness. Then I have another session later and, if I can, again in the evening, to clear the day’s residue and bring myself back to a more peaceful state of mind.

How has meditation changed you?

In so many ways it’s a little hard to summarize. When I first began to meditate, I was astounded. How could I have been so out of touch with my own depths and inner resources?

That led me to explore different spiritual disciplines. To my surprise, they were helpful.

I used to think of religion as a relic of primitive society. Why was I being helped by these archaic practices? A defining moment came when I realized that hidden by conventional religious institutions were practices for helping people discover insights, love and compassion. Through my research, I began to appreciate the reservoir of wisdom available in these traditions, which had been overlooked or not adequately understood in our culture.

What are other benefits of meditation?

Meditation can help us overcome what the philosopher Kierkegaard described as the “tranquilization by the trivial.” Our media, our advertising, keep us focused on the trivial to get us to buy what we don’t need.

Meditation is a quiet inner revolution. It reorients us, and reminds us of what’s important, what really matters. Once people become grounded in meditation, they become more attuned to the sacredness of life.