Cracking cancer's code

Recent additions to UCI’s team attacking deadly disease on multiple fronts

Few natural challenges are as humbling to humanity as cancer.

It springs from the very core of physiology – life’s elemental code suddenly scrambled, a piece of the biological blueprint transformed from creator to destroyer. More sobering still, cancer destroys through its own dark parody of the fundamental process of reproduction. From cell to cell, organ to organ, cancer blazes as life dims.

This deadly enigma challenges the greatest minds, and universities. Now, with the recent addition of world-class molecular biologists to its already strong cancer research core, UCI is becoming a key front in this clearly vital battle.

At the center of this effort is the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCI Medical Center, one of only 39 centers in the country recognized by the National Cancer Institute for its outstanding research, clinical studies and treatment of this damaging disease. Among its many specializations, the center is renowned for its efforts to understand and eventually cure breast cancer.

“Excellence in cancer research is a long-standing strength of UCI,” says Hung Fan, Chao Center co-director and professor of molecular biology and biochemistry in the School of Biological Sciences. “We have vigorous research programs in carcinogenesis, growth factors and signaling, virology, structural biology, and developmental biology. Synergy among our investigators in these areas, along with collaborations with other scientists, epidemiologists and clinicians, will ultimately lead to new cancer therapies, preventions and cures.

“We have recently recruited a number of outstanding investigators,” Fan notes. “An important factor has been the completion of Sprague Hall, a state-of-the-art research facility dedicated to cancer and genetics.”

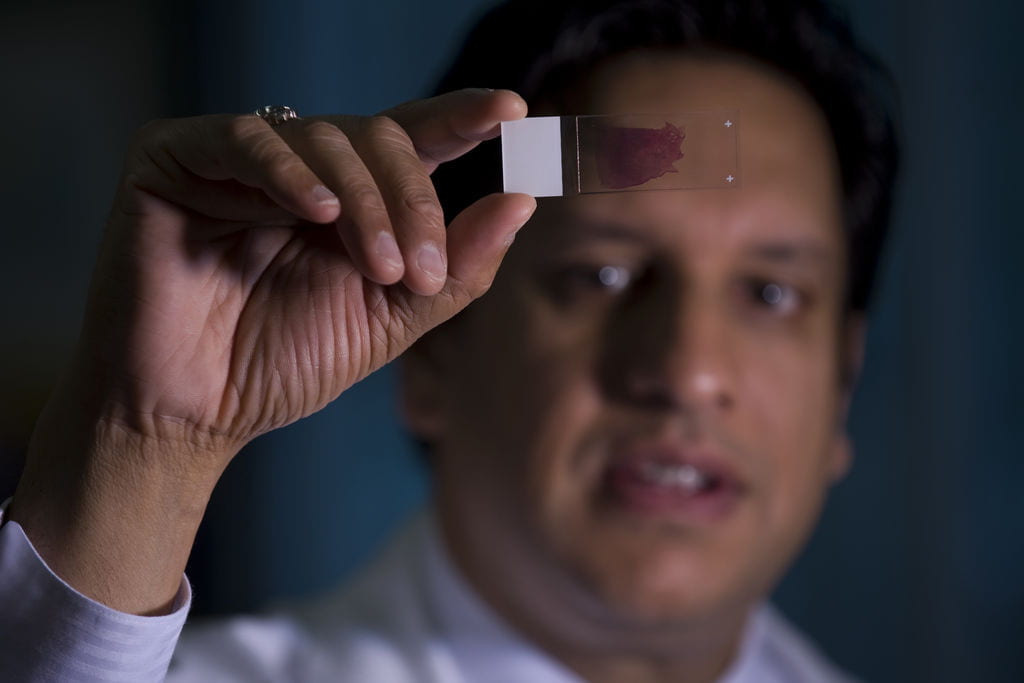

Even more important than new facilities are the cancer experts who utilize them. Among UCI’s recent research reinforcements is Dr. Rainer Brachmann, who joined the College of Medicine last year and quickly became a major force behind a broad collaboration among four schools and 10 laboratories. Across a vast landscape of scientific expertise that includes bioinformatics, biophysics, chemistry, genetics and molecular biology, the group is searching for drugs able to eradicate the most difficult-to-treat human cancers, those caused by mutations that inactivate a key tumor-suppressor protein known as “p53.”

TURNING THE SWITCH

Understanding p53 has become something of a Holy Grail for many UCI researchers. Eva Lee, who came to the campus in late 2001 with a joint appointment in the College of Medicine and School of Biological Sciences, is a pioneer in p53 research that illuminates the origins and possible treatments for breast cancer. The key, she explains, is to simply “wake up the repair shop in the cell.” Once p53 is switched back on, the body itself will excise cancer.

Although inactivation of the p53 gene has been implicated in nearly half of all human cancers, there are other important tumor-suppressor genes that work in complex combinations to fight cancer or, when damaged, allow a quick spread of the disease. This research path is being mapped out by Wen-Hwa Lee, Eva Lee’s husband, who was recently named Donald Bren Professor of Biomedicine in the College of Medicine after 12 years as founding director of the University of Texas Institute of Biotechnology.

“Legend” is a word often used to refer to Wen-Hwa Lee, and he will clearly play an important role in creating a legendary research history at UCI. In the late 1980s, he led a team at UC San Diego that discovered the first human cancer susceptibility gene. Mutation of this gene was implicated in retinoblastoma, or eye cancer, and later in bone, lung, breast and other cancers.

“Previously we blamed everything,” Lee says of his eye cancer discovery. “We blamed electricity, we blamed too much sausage – but in this case it’s clear: It’s the gene’s fault.”

TARGET IN SIGHT

At UCI, Lee plans to focus his research on developing new compounds that will disrupt end-stage cancer cells. The goal is a small molecule that, when injected into the blood stream, will act as something of a biological cruise missile to target, shock and awe the cancerous cells.

In this research, he will make valuable use of a breast cancer model developed by his wife. UCI Chancellor’s Professor of Developmental and Cell Biology and of Biological Chemistry Eva Lee has experimented with mice to yield a predictive model researchers have been able to apply when testing new theories and treatments.

“She developed the model, and I will develop the molecule,” Lee says. “We can use this model to test a new drug and how it works in combination with old drugs.”

New drugs based on small, life-saving molecules also are the focus of the ongoing collaboration led by Dr. Brachmann. The genesis of this massive effort was the observation that by making changes to specific amino acids of a damaged p53 protein, its function is often restored.

In the near term, this spirit of constant innovation and shared discovery is likely to continue drawing great research scientists to UCI. Someday, it may prove to have been the essential key to solving cancer’s puzzle – and finally conquering this merciless, ancient plague.

| CROSS-CAMPUS COLLABORATORSIn addition to the interactive efforts of Professors Eva and Wen-Hwa Lee, the breadth and diversity of Dr. Rainer Brachmann’s group illustrate UCI’s multidisciplinary approach to cancer research and discovery. The researchers and their respective faculty appointments are:

Baldi serves as director of UCI’s Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics. Chamberlin serves as director of UCI’s Center for Interdisciplinary Chemical Synthesis. |