Studying the Students

UCI to pilot a national survey on undergraduate life and learning – with an eye to improving both

The framed “Doonesbury” comic strip in Richard Arum’s office sums up a quandary facing hundreds of American universities. It shows a dean telling his boss about a report that says nearly half of U.S. students made no gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning or writing skills during college, partly because they spent so much time socializing instead of studying.

His boss shrugs off the numbers. “As long as we give them good grades and a degree … who cares if they can’t reason?” he asks.

The dean replies: “Uh … employers?”

The cartoon then switches to a high-rise corporate office, where a supervisor is asking a young hire why he’s late. The answer: “I got trapped in a paper bag.”

Although the punchline is fictional, the statistics behind it are real. They come from a 2011 study that Arum and another sociologist conducted at two dozen colleges across the country. (UCI wasn’t included.) Pointing at the comic strip, Arum jokes that being immortalized in the Sunday funnies “is the high point of my career.”

Actually, the report he co-authored – which also noted that modern students devote half as much time to homework as their 1960s counterparts – sparked extensive media coverage and prompted reforms at a number of schools.

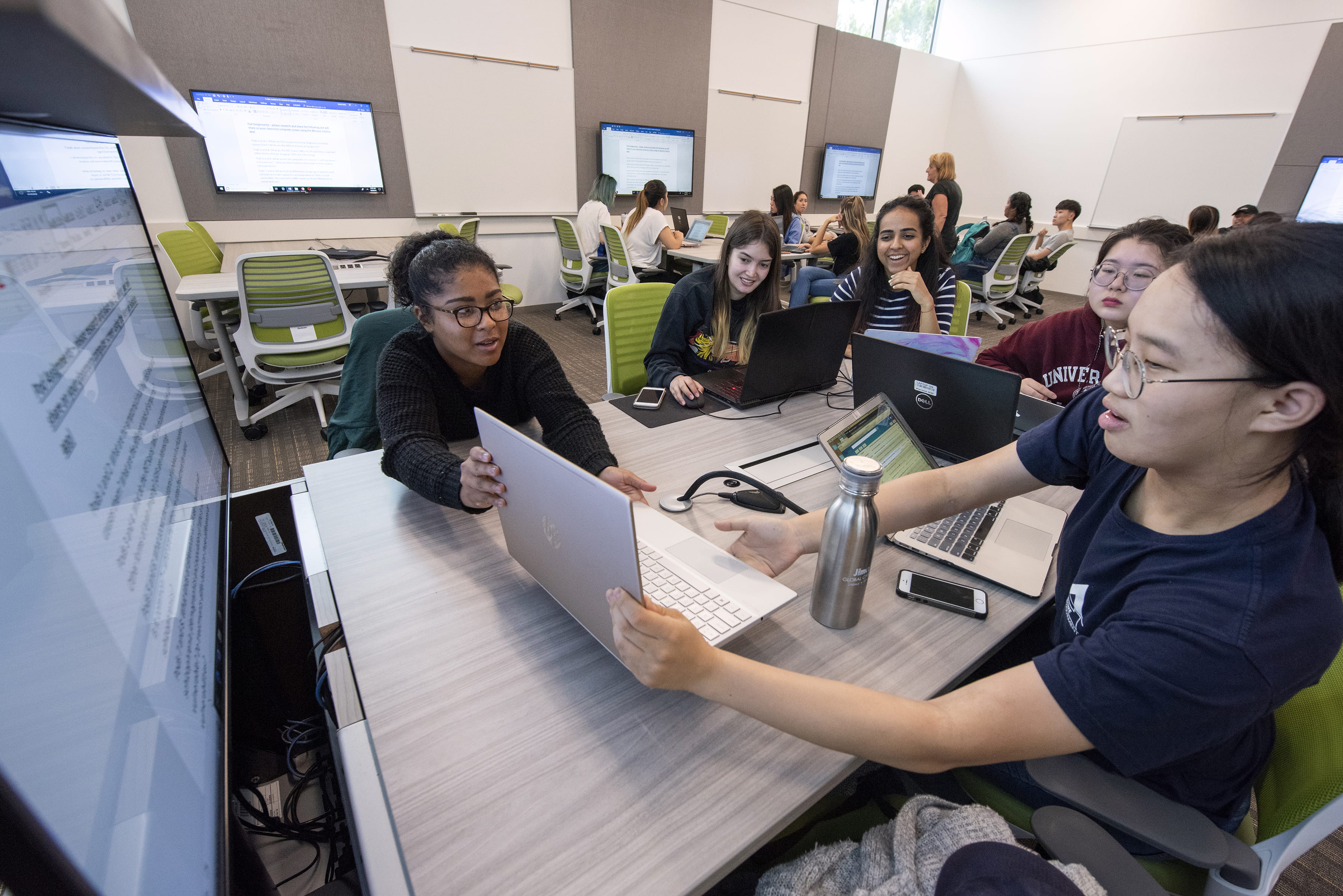

Eight years later, as dean of UCI’s School of Education, Arum is poised to find out if anything has changed. This fall, he’s launching a new survey – one that promises to deliver unprecedented insights – in partnership with Michael Dennin, vice provost and dean of undergraduate education. Using pop-up smartphone polls, artificial intelligence and untapped school databanks, the pilot program will be funded with a $1.1 million grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

It’s the academic equivalent of Amazon or Netflix mining customer information to pinpoint and better serve their needs, says Arum, who chaired New York University’s sociology department before coming to UCI in 2016. Ultimately, UCI’s survey will be rolled out nationally and the results used to bolster student knowledge, graduation rates and career progress.

“Efforts to discover what’s working and what’s ineffective at universities are important to improving student success,” says Michael Itzkowitz, who directed the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard program and is now a senior fellow at Third Way, a Washington, D.C., think tank. UCI’s diverse student body and widespread reputation for supporting disadvantaged undergrads make the campus a logical testing ground for the project, he adds.

In announcing the study, Mariët Westermann, Mellon Foundation executive vice president for programs and research, noted that “colleges and universities face growing pressure to prove their value to their students and society at large.” Ideally, she said, the data will “help all of us understand better what the worth of a liberal arts education is.”

Asking the Right Questions

Gauging what makes college students tick isn’t a novel quest. Researchers have been trying to analyze, categorize and synthesize undergraduate psyches for decades.

Think back to when you were about 6 years old. How often did your parents or other adults in your house limit your TV watching? Take you to an art museum? Punish you for bad grades?

When you were 13, how often do you recall witnessing students kissing or “making out”? Students cutting school? Verbal abuse of teachers by students?

Did your high school have tennis courts? A theater for dramatic productions? Metal detectors at school entrances?

Those questions were part of a 1999 survey (also sponsored by the Mellon Foundation) on the backgrounds and values of freshmen at 28 elite American colleges. Other studies have tracked everything from postgraduate salaries to newspaper readership to affinity for Asian hip-hop artists. Inevitably, the goal of such inquiries is to suss out how various factors influence student performance.

Unfortunately, the findings are largely outdated, Arum says, citing demographic shifts, antiquated polling methods and a past tendency to canvas only top-ranked universities. To tackle the issues that plague colleges of all stripes, a broader snapshot is needed, he says, and UCI – which was recently designated a Hispanic-serving institution – is a perfect starting point because “our student body looks more like the future of America,” especially as the number of Hispanics rises nationwide.

In addition, campus researchers plan to use new survey tools. “You’re not going to get good answers with multiple-choice questions,” says psychologist Jacquelynne Eccles, a Distinguished Professor of education and partner on Arum’s survey team.

Although details have yet to be hashed out, she hopes to try such open-ended prompts as “Tell me what you want to do with your life and why” and “Design an ideal community.” AI software will analyze the maturity and complexity of student answers, she says.

Other topics may include favorite television shows, the music a person listens to (and whether it’s to relax or for some other purpose) and descriptions of close friends. “If we want to understand college students, we need to measure all of this,” Eccles says.

Also on the drawing board are real-time “experiential” questions – “Where are you right now?” “What are you doing?” “Who are you with?” “How do you feel?” – that will pop up on student cellphones at random hours.

“We don’t really know what students are doing with their time,” Eccles explains. “We know what they’re not doing: Many don’t go to class.” At Harvard University, for instance, average attendance in large lecture courses is just 60 percent, according to a 2014 study by the school. (Undergrads are more likely to show up if it counts toward their grade, Eccles adds, “but that doesn’t mean they’re paying attention.”)

Ideally, charting student activity and moods will produce data akin to what a smartwatch collects, enabling administrators to better design programs and perhaps even anticipate and prevent problems, Eccles says.

Itzkowitz agrees, noting that colleges have begun experimenting with “predictive analytics” to help struggling students. Georgia State University, for example, boosted its graduation rate by using data to detect red-flag behaviors and determine which interventions were most likely to get students back on track, he says.

An Untapped Gold Mine

This fall, Arum’s team will begin tracking a random sample of 500 UCI freshmen, 250 junior transfers, 250 continuing juniors and 50 freshman honors students. All who opt in will receive small stipends for participating in the two-year study, and the statistics and details gathered will be protected and anonymous, Arum says.

In addition to tabulating written survey and smartphone questionnaires, the researchers will tap into vast “data warehouses” at the school. UCI is “awash in information that nobody is doing anything with,” Arum says – everything from course selection patterns to family demographics. In contrast to private industry, universities are “behind the curve” when it comes to using data, he says.

One of the biggest statistical gold mines is Canvas, the classroom software system that hosts syllabi, course readings, online discussions and homework assignments across campus.

From that, the team can record how often students go online in a course, how they participate and how their activity compares to that of classmates, says Mark Warschauer, a UCI professor of education and informatics.

Writing assignments submitted through Canvas can be analyzed – via automated linguistic tools that evaluate vocabulary, syntax and coherence – to assess academic progress, Warschauer says.

That’s a better barometer of learning than a grade report, Arum suggests.

Eventually, the survey template created and tested by UCI will be adapted for a national longitudinal study, dubbed College and Beyond 2.0, overseen by the University of Michigan.

“What we’ll know in a few years will be quite limited,” Eccles says. But over time, as researchers follow up with students after graduation, “this project has tremendous potential to reshape higher education,” Arum adds.

In particular, many schools are looking for ways to shore up their graduation rates. “It’s a dark secret among college and university administrators how poorly we’ve done in this area,” Arum notes. Across the U.S., roughly half of all students drop out or fail to get a degree within six years.

Even at UCI, where 88 percent of undergraduates earn a bachelor’s degree in that time frame, he sees room for improvement. “If you landed only 88 percent of your airplanes,” Arum says, “you wouldn’t be satisfied.”

Originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of UCI Magazine.