Interplanetary Obstetrician

Physician alumnus researches (future) life on Mars while teaching medicine at UCI

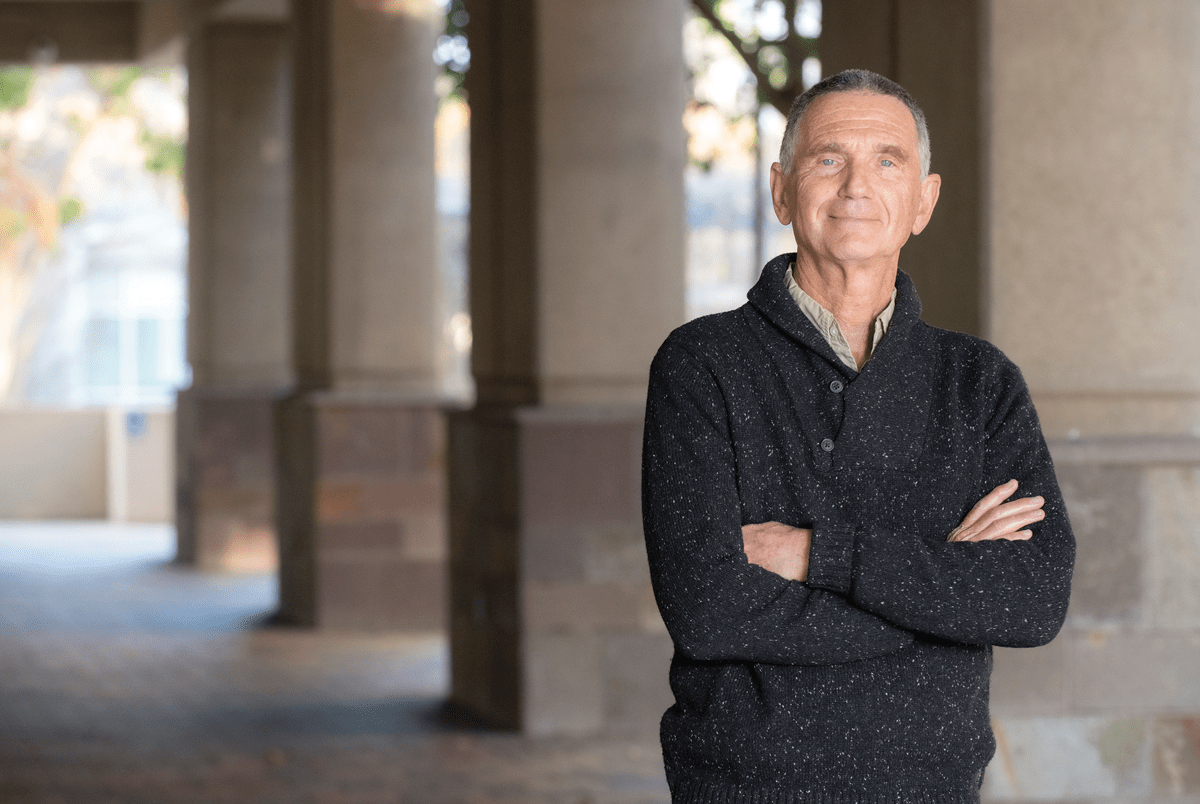

In the song “Rocket Man,” Elton John famously warned, “Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids.” Maybe so, but we should still plan for Red Planet pregnancies, says Dr. Jon Steller, a NASA physician and assistant clinical professor of maternal fetal medicine at UCI.

The combination of human nature and imperfect birth control methods makes diaper-clad Martian babies inevitable once earthlings start colonizing the solar system, he predicts.

However, nobody knows if the extraterrestrial tots and their moms will be healthy.

Although setting foot on Mars is still a few decades away, scientists are woefully behind when it comes to researching the effects of cosmic radiation and microgravity on reproduction, says Steller, who stumbled into space medicine by way of volleyball, a trek to Ukraine and a children’s birthday party.

Originally from Fresno, Steller was recruited in 2004 to play volleyball at UCI, where he became an NCAA All-American and helped the team capture two national championships. Majoring in both neurobiology and classics, he was named Outstanding Student-Athlete at UCI’s Lauds & Laurels ceremony in his senior year.

But with a name like Jon Glenn Steller, a career involving outer space wound up being more fitting than one in sports. In 2007, he was offered the chance to either join an archeological dig in Rome or go on a three-week humanitarian mission in Ukraine. He chose the latter, visiting orphanages and setting up a summer camp for homeless children.

The experience cemented his interest in becoming a doctor and helping others.

The summer after graduating in 2009, he married his high school sweetheart and enrolled in UCI’s School of Medicine. Later, during his residency in obstetrics & gynecology at the university, Steller took his two young daughters to a space camp birthday party.

It would change his career path.

“I was having a mini quarter-life crisis,” he recalls. The host of the party worked for Boeing, overseeing the robotic arm that enables capsules to dock with the International Space Station, and her friends were with Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “They were all talking about their space research, and I became extremely jealous,” Steller says. That night, he scoured the internet for ways to apply his OB-GYN specialty to the cosmos.

After digging up a few decades-old papers on pregnant rats in orbit and astronaut gynecology, he emailed the scientists involved, a former NASA flight surgeon and a college professor. “Both seemed happy that somebody young was interested in the field,” he says.

Steller soon began collaborating with them on projects, won a grant for new research and – in 2020 – landed a NASA physician job, working on a team that aims to reduce the medical risks on long spaceflights. Among the conditions he tries to stave off for female astronauts are ovarian cysts, bone density loss and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Separate from his NASA work, he launched a lab at UCI to explore how radiation and weightlessness affect animal fertility and offspring. So far, the experiments are earthbound, but Steller hopes to eventually direct trials in orbit. The ultimate goal, of course, is preparing for Mars.

One of the chief concerns is cosmic radiation. On Earth, the atmosphere acts as a protective shield. But in space, the exposure level skyrockets, bombarding astronauts with a year’s worth of terra firma radiation every day.

Low gravity also takes a toll.

Scientists have studied what those factors do to people’s eyesight and brain function, Steller says, “but we don’t know what happens to reproduction and development.”

Unfortunately, funding to investigate such topics shriveled after the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986, he says. But if humans are serious about colonizing the moon or voyaging to Mars in the next 30 to 50 years, he adds, a lot more research is needed.

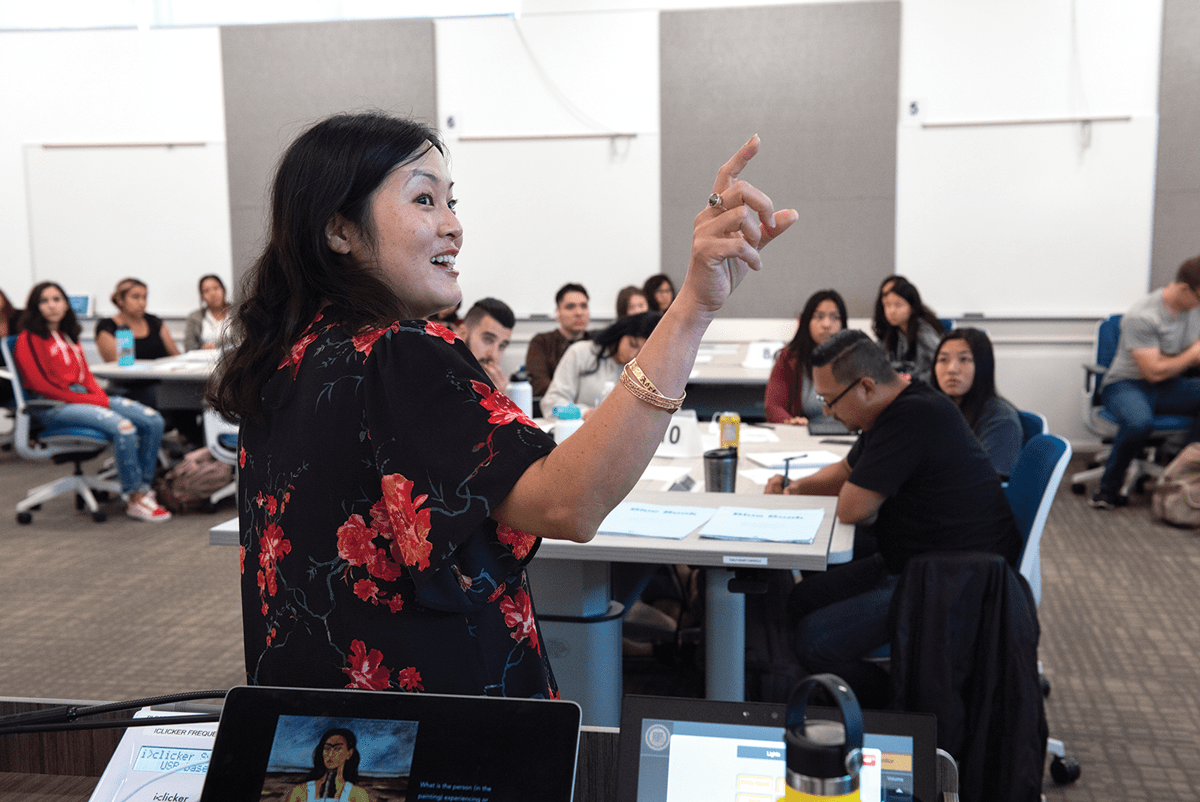

In the meantime, Steller has his hands full with Orange County pregnancies. About 60 percent of his time at UCI is devoted to seeing patients. Another chunk is spent teaching “the art of doctoring,” including social responsibility, to future physicians at UCI’s School of Medicine.

In 2017, Steller won OB-GYN mentor and instructor of the year honors at UCI. A few years earlier, to expand his educational reach, he launched a web resource, FLAME, featuring a collection of five-minute lectures and presentations on a panoply of medical topics, from abdominal pain to smoke inhalation. The site gets hundreds of hits each week from aspiring doctors and residents, he says.

Outside of work, Steller writes and edits fantasy novels, plays indoor and sand volleyball, and serves as vice president of the Red Hibiscus Foundation, which provides healthcare to underserved people around the world. That last sideline is the most recent manifestation of his desire to help those in need. Tattooed on his right arm are Greek numbers representing a Bible passage from Philippians that exhorts, “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves.”

As an undergrad, Steller helped build houses and provide healthcare in Mexico. During medical school, he led the Flying Samaritans chapter at UCI, which ran a clinic in the neighboring nation. Even when cartel violence spurred the University of California to suspend travel south of the border, he went on his own. “I have a social responsibility to step outside my comfortable Southern California life, whether it’s 10,000 miles or 10 minutes from home, because I have the capacity to make a difference,” he told UCI News at the time.

But lately, family and work duties have curtailed his volunteer activities. “There are only so many hours in the week,” Steller notes – unless he makes it to Mars, which has an extra 37 minutes in each day and 10 more months per year.