Southeast Asian Archive holds history, heritage

UCI Libraries’ one-of-a-kind collection documents the experience of post-Vietnam War immigrants.

The struggles and triumphs of immigrants from Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are well documented by UC Irvine’s Southeast Asian Archive. Items in the collection range from paintings by artists in refugee camps to business directories of Orange County’s Little Saigon.

Researchers from around the world have visited UCI to study the archive, the only one of its kind that continues to trace the community’s growth in the U.S. since the 1975 end of the Vietnam War.

UCI Libraries established the Southeast Asian Archive in 1987. Materials include books, refugee orientation pamphlets, government documents, clothing, reports and surveys, journals, newspaper clippings, video and audio recordings, photographs and artwork.

For members of the Vietnamese American Community Ambassadors – an official chapter of the UCI Alumni Association – the collection is a deeply personal reminder of how far they have come since fleeing their war-torn homeland.

“I think the only English words I knew when I arrived in the U.S. as a child were ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘apple’ and ‘car,’” says Jack Toan ’95, who lived in a Hong Kong refugee camp before his family’s church-sponsored move to South Carolina and subsequent resettlement in Orange County.

Today the father of three is regional vice president of the Wells Fargo Foundation in Irvine and works with VACA to promote the archive with fundraising events and outreach in Little Saigon.

“My generation is somewhat Americanized, but we’re still connected to our heritage,” he says. “Our kids may slowly lose that, but this collection keeps our cultural ties strong and will show future generations how our community grew and flourished.”

Toan, who earned a bachelor’s in biology and an M.B.A. at UCI, says the recent budget climate has pushed Vietnamese American alums to get more involved with the archive.

“We were initially concerned that the UC might not see the significance of this collection,” he says. “But UCI Chancellor Michael Drake has been very supportive of the archive and fully understands the importance of preserving it.”

On Tuesday, Dec. 7, at the Institute of Vietnamese Studies in Westminster, Drake and VACA President Daniel Do-Khanh ’93 will celebrate their joint commitment to raise funds to hire an archivist for the collection, so that donated materials can be processed and quickly made available for researchers and the general public.

Do-Khanh says his group will reach out to business leaders in Garden Grove and Westminster. The area, known as Little Saigon, is home to restaurants, cafes, delis and banks catering to Southeast Asians.

“We’re all at a stage in our lives where we’re settled in our careers and ready to give back to the university,” says Do-Khanh, a lawyer who grew up in Garden Grove and runs a business and employment litigation firm in Irvine. “We want people in the immigrant community to know that the Southeast Asian Archive is a safe place for them to donate documents and personal items.”

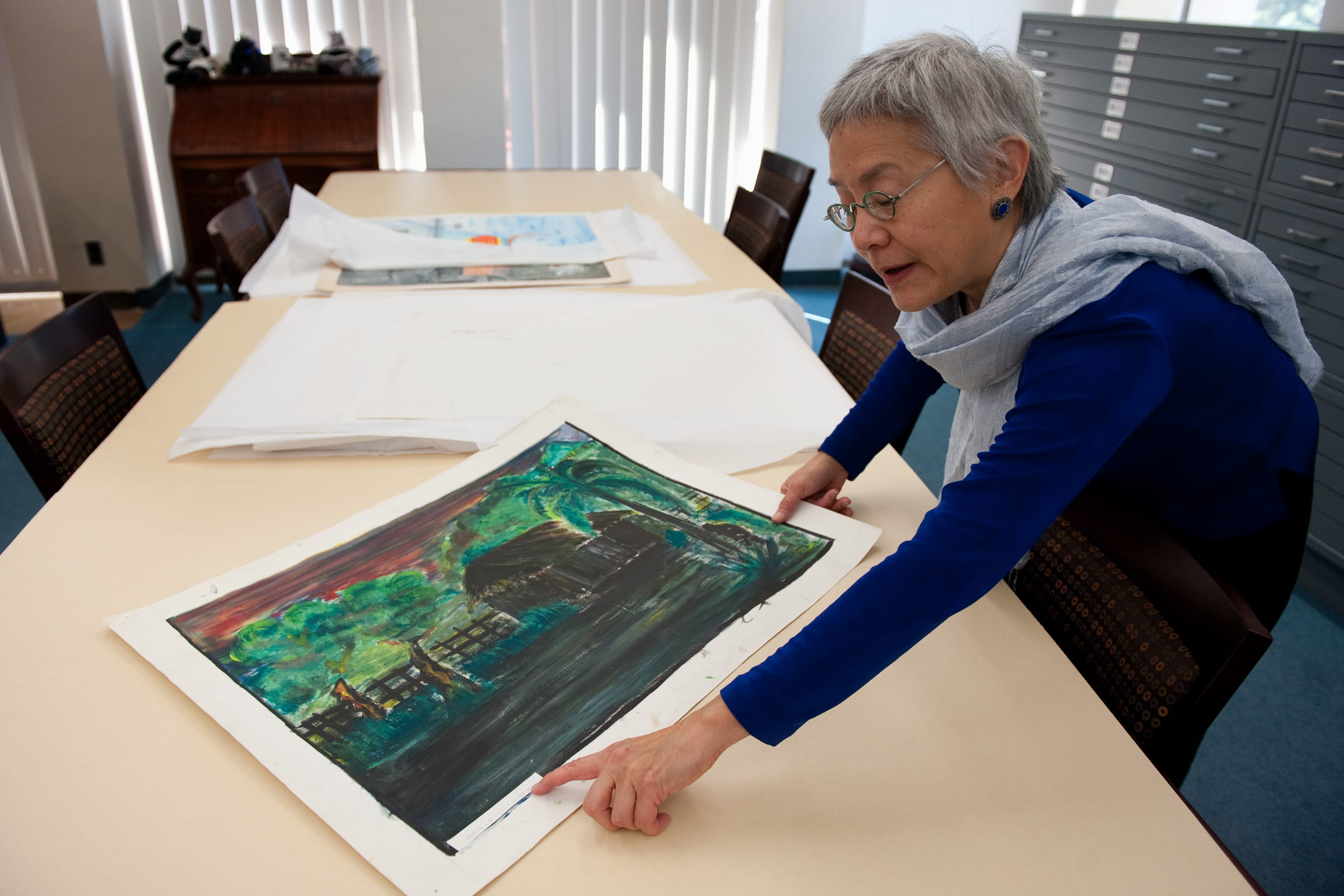

UCI librarian Christina Woo helps researchers, students, faculty and community members navigate the labyrinthine collection, housed on the third and fifth floors of Langson Library.

“We’ve recently had researchers and graduate students from Brown University and the University of North Carolina stop by the archive,” Woo says. “Last year, a researcher from Montreal came to continue his study of Vietnamese Canadians. People around the world know this as the premier collection of its kind.”

Recent research topics, she says, have included the Hmong experience in refugee camps, fiction writing by immigrants who came to the U.S. as young children, beauty pageant culture in the Southeast Asian community and the proliferation of Cambodian doughnut shops.

Ma Vang, a doctoral student in ethnic studies at UC San Diego, visited the archive various times over seven months last year to learn about Hmong refugees and the war in Laos.

“I visited both the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library & Museum and the Vietnam Center & Archive in Texas, and although they had good declassified materials about Laos, they were missing the perspective of the people who were actually affected by war,” says Vang, recipient of the library’s 2009-10 Southeast Asian Archive Anne Frank Visiting Researcher Award. “Research at the archive is crucial to how we understand the wars in Southeast Asia.”

Tina Powell, a Fordham University graduate student who studies the literature of the Vietnamese diaspora, says the archive is critical to her work because most available information concerns the Vietnam War and militarism.

“My home university doesn’t have access to publications by the local Vietnamese American community,” she says. “The most helpful documents, so far, have been those relating to the 25th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, resettlement materials and brochures, and zoning and building plans for Little Saigon.”

Powell, whose fascination with the Vietnam War led to an interest in the perspectives of people other than U.S. soldiers, spent three full days at the archive this summer. She keeps up with her research using UCI’s online system to access archive databases.

On a recent afternoon, Woo pulled out several of the collection’s representative items, such as an oral history of the Vietnamese community in Orange County and posters and programs from Cambodian, Hmong and Laotian events and festivals. More unusual articles include a Hmong hand-embroidered jacket and a qeej, a popular wind instrument made from bamboo.

Nowhere is the pain and uncertainty of refugee life more evident than in the archive’s paintings by Vietnamese artists detained in Hong Kong camps. Members of the now-disbanded UCI student group Project Ngoc donated the works after a late-1980s visit to the camps.

Many of the paintings include cries for help and images evoking freedom, such as the Statute of Liberty. Others depict the Vietnamese landscape, with its lush jungle landscape and sandy beaches. “You could say that it’s a much more effective form of protest than letter writing,” Woo notes.

The refugee experience is never far from the minds of people in the local Southeast Asian community. Moreover, they hope the collection can serve as a lasting reminder of those early struggles to future generations.

“This archive is a gem that you can’t find anywhere else,” Toan says. “And it’s a very tangible way for the Southeast Asian community to reconnect with UCI, which has educated so many of its members throughout the years.”