Bacteria teach evolution, climate adaptation

How will Earth’s tiniest organisms adapt to climate warming? UC Irvine scientists are consulting bacteria in an effort to find out.

How will Earth’s tiniest organisms adapt to climate warming? UC Irvine scientists are consulting bacteria in an effort to find out.

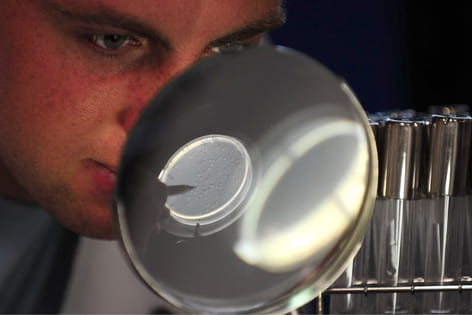

By warming E. coli and studying how their offspring evolve at higher temperatures, biologists can watch an accelerated evolutionary process and learn how bacteria adapt to warming – and what they lose in the process. For example, do bacteria that thrive at warmer temperatures fare poorly in cooler environments?

Al Bennett, Brandon Gaut and Tony Long are conducting this study, supported by a $900,000 grant from the National Science Foundation. The study builds on previous work by Bennett and former UCI scientist Richard Lenski, who also studied E. coli to learn more about evolution.

“We are looking at many more evolved lines, hoping to better understand the broad array of genetic changes that contribute to a single trait – adaptation to a higher temperature,” said Gaut, ecology & evolutionary biology professor and department chairman.

E. coli is found in the intestines of warm-blooded animals, where the temperature is roughly 37 degrees Celsius, or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

In this study, UCI scientists are warming the environment to 42 degrees Celsius, or 107.6 degrees Fahrenheit, then evolving 100 lines of E. coli for one year and analyzing their genetic sequences. By doing this, they hope to identify the exact genetic mutations that lead to adaptation.

This project also will include education for K-12 teachers. Next summer, ecology & evolutionary biology lecturer Brad Hughes will give a course on evolution to teachers, using the E. coli system as a model.

“Teachers will learn about the E. coli system and do experiments of their own,” said Bennett, biological sciences dean. “It is a non-controversial way to talk about the basic processes of evolution.”