Meeting the environmental justice challenge

UCI graduate students honored by EPA for bioremediation project video

An interdisciplinary team of UCI graduate students has claimed the top prize in Phase 2 of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Video Challenge for Students. Working with representatives from the Orange County Environmental Justice community organization, the group produced a video about a proposed project to enlist Santa Ana residents in bioremediation efforts to remove lead from soil contamination hot spots throughout the city.

“Thanks to the hard work of OCEJ and other local organizations, the city of Santa Ana’s general plan now gives priority to environmental justice, and they’ve begun to appreciate the important role bioremediation can play,” says team member Tim Schutz, UCI Ph.D. candidate in anthropology. “Engaging in the Research Justice Shop fellowship and working with the UCI EcoGovLab were instrumental in forming our interdisciplinary student team, and the video we created served as a great motivator.”

This first-place finish in the EPA video contest was preceded by a victory in Phase 1 last August. For that challenge, the researchers submitted a video outlining the problem of lead pollution in Santa Ana, its sources (emissions from older, lead-containing gasoline along with lead paint), a system for geographically identifying soil contamination hot spots, and impacts to the surrounding communities.

The Phase 2 video entry proposes a project that relies on the power of certain plants and fungi to extract lead from the soil as they grow. The UCI grad students developed a plan to implement bioremedial cultivation involving community partners in Santa Ana.

“Mycorrhizal fungi are present in more than 80 percent of plant species on Earth, and research has shown they play a vital role in facilitating the uptake of soil lead in plants,” says team member David Banuelas, Ph.D. candidate in developmental and cell biology. “The goal of this project is to understand how the application of mycorrhizal fungi can enhance the uptake of soil lead.”

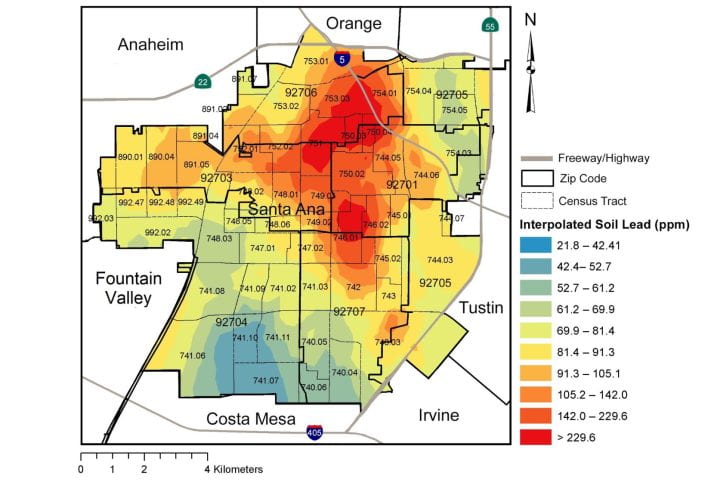

Santa Ana is crisscrossed with major highways and thoroughfares, and historically, many leaded gasoline-powered vehicles traveled these roads, with a decline happening only after leaded gasoline began to be phased out in the U.S. around 1975. In the first phase of their work, the UCI researchers created heat maps of the city to identify places where lead pollution was highest and therefore most likely to affect human health.

Phase 2 calls for a large number of citizen environmental bioremediation volunteers to plant the fungi-laden vegetation and then remove it after some growing time, theoretically taking the lead away. OCEJ is instrumental in this part of the project, helping to recruit, train and motivate these community members.

The researchers consider this bioremediation method to be less expensive and more effective than simply removing contaminated soil and transporting it to a different site, which would likely cause harm to a different subset of Orange County’s underserved population.

“In Santa Ana, we will use native plant species with mycorrhizal fungi to enhance remediation efforts. After a growing season, the native vegetation will be removed to determine if mycorrhizal fungi have increased remediation efforts,” Banuelas says. “Our project will help build green space with native flora while working to remove lead from soil, providing a dual benefit to the community.”

Shahir Masri, associate specialist in the UCI Program in Public Health’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, has been assisting the team by carrying out data analysis.

“Our students and community volunteers have done a terrific job of identifying a problem that persists in a historically underserved community near the UCI campus, coming up with ways of analyzing the dilemma and then devising a solution,” Masri says. “Each step along the way has represented a partnership between academics and local residents who are most impacted by soil lead contamination in their neighborhoods.”

Schutz adds: “Our cross-disciplinary team holds a shared understanding of how environmental injustice happens, and that enabled us to see the different stakeholders involved, the barriers between communities and government agencies, and the actions that could empower residents.”

Chris Frey, assistant administrator of the EPA’s Office of Research and Development, says: “This challenge showcases how collaboration between the next generation of environmental justice advocates and community organizations can produce truly innovative ideas to address environmental and public health issues affecting communities. We are encouraged by each team’s exceptional efforts and look forward to creating pathways for continued community capacity building that will help us to achieve our mission to protect human health and the environment.”

Total prize money for the entry was $60,000; $50,000 goes to OCEJ and $10,000 to participants on the UCI side. Now that the EPA’s video competition phases are complete, the students will use the funds to pursue the next stages of the project.

Joining Banuelas and Schutz on the UCI team are Annika Hjelmstad, Ariane Jong-Levinger and Ashley Green of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering; and Alexis Guerra of the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health. Connie McGuire, director of community relationships in the Research Justice Shop of the Newkirk Center for Science & Society, contributed to the project as a faculty advisor.

Support this and other work at UCI by supporting the Brilliant Future campaign, which aims to raise awareness and support for UCI. By engaging 75,000 alumni and garnering $2 billion in philanthropic investment, UCI seeks to reach new heights of excellence in student success, health and wellness, research and more. Learn more by visiting https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu.