K-12 post-pandemic classroom: reading, writing, recovery

UCI professor of education discusses COVID-19’s lasting impact

K-12 students are on track to return to school this fall, but the pandemic will still be in the classroom – figuratively. The consequences of the sudden shift to a virtual environment – ranging from learning loss, achievement gaps and inequitable internet access to compromised social development, emotional well-being and physical health among students – will be all too evident.

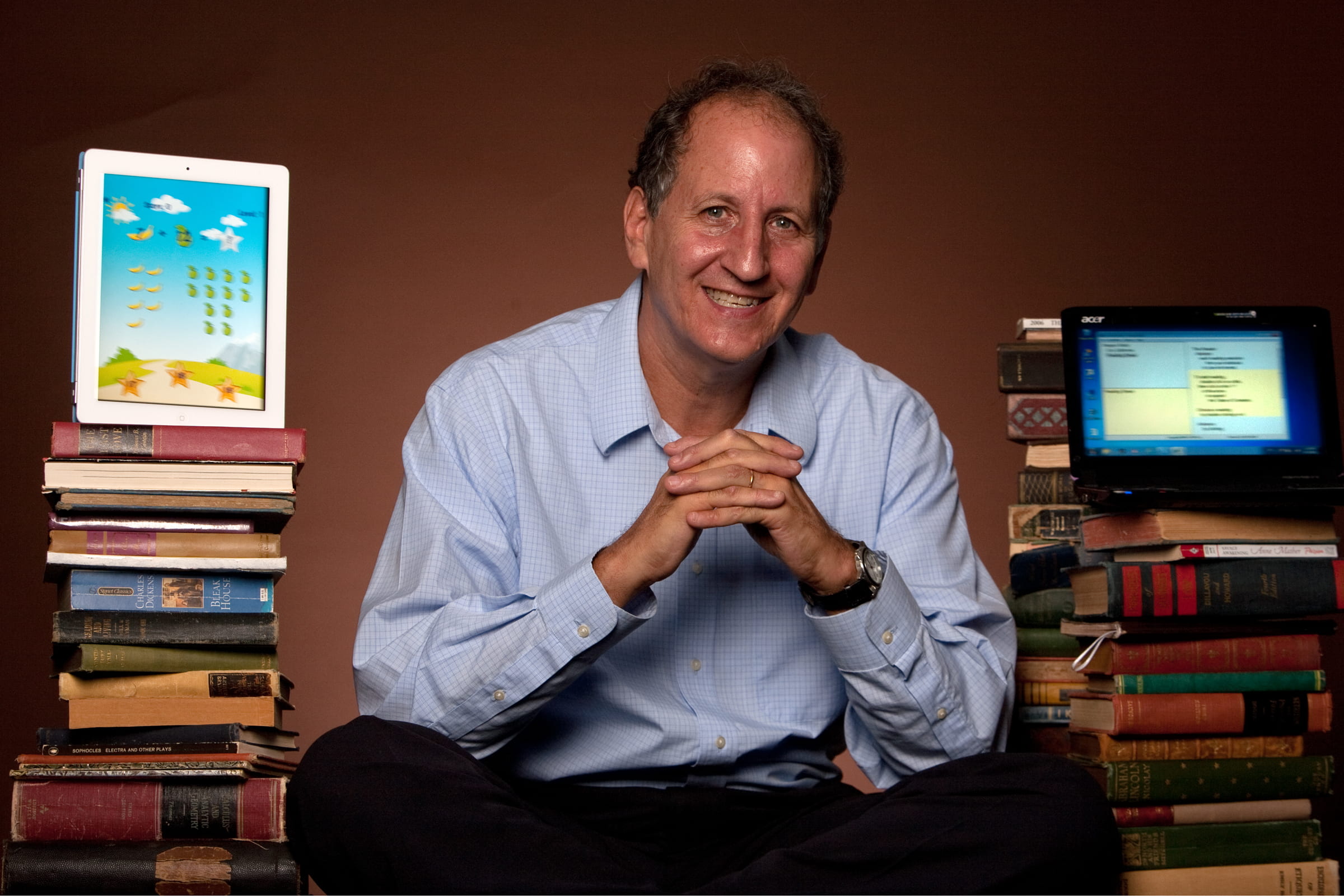

“There are going to be greater achievement gaps and social adjustments in the classroom, as some kids have thrived in the at-home learning environment and other kids have basically dropped out,” says Mark Warschauer, UCI professor of education and informatics. “This is something districts need to be aware of and prepared to deal with. Those pandemic-induced issues are not going to immediately disappear when we start going back to school.”

Achievement gaps and learning loss

There is much public debate about whether or not students should take the annual state assessment standardized tests this spring. One side of the argument is that it would be unfair, because not being in school means they’re behind, and the pandemic has stolen so much of their childhood that they just need to play.

Warschauer, however, says that “more data is better, so I’m in favor of school testing so we get an accurate assessment of student achievement levels.” And while it’s expected that not being in the classroom means many students will have experienced some measure of learning loss, for lower-income students, COVID-19 is not the only culprit, he says.

“When you get to the summer, middle- and upper-middle-class parents are putting their kids in enrichment camps or exposing them to lots of reading or taking them to museums. Lower-income kids have fewer opportunities in the summer, which is when they really fall behind, and it accumulates summer after summer,” Warschauer says. “So when they’re already behind and have fallen even further behind because of the pandemic, I feel kids need to have after-school or Saturday sessions or summer learning opportunities to help them fill those achievement gaps.”

Technology in the classroom and at home

Warschauer doesn’t believe that online learning will replace public schooling, but he does think that it will be increasingly integrated into classroom instruction, as teachers and students have gotten more comfortable with digital tools. “The virtual and in-person realms have different benefits, so this will be a plus,” he says.

The digital divide came into sharp focus during the pandemic. The abrupt shift to a virtual space was difficult for everyone, but inequitable internet access and a lack of computers made it almost impossible for some students to engage and learn remotely. Those with special needs and English learners found it harder to obtain the services they needed.

“There’s always been this pretense that kids didn’t need internet access at home because they could do their work in school,” Warschauer says. “Eventually, what that meant was that in wealthier districts, students had more opportunities for rich out-of-school learning, and students in poorer districts had less of those opportunities. So I think this wholesale acceptance of at-home internet access being optional rather than a necessity for fair and equal education has been blown away.”

The solution, he says, is for internet access to be designated a public utility like telephone service was in the last century.

Social adjustments

Supporting students’ social and emotional needs during the pandemic has been a key part of education. Isolation from friends, classmates and teachers presented challenges to children’s social development, emotional well-being and physical health, with an added burden in households experiencing economic insecurity.

“For the majority of kids, returning to in-person instruction will be a very positive development. But there are some introverts who have secretly enjoyed not having to get up and face a group of people every day, which is something that teachers and counselors will have to pay close attention to,” Warschauer says. “And addressing all the academic issues the pandemic revealed and the social consequences caused by classroom disruption will take time and patience. It’s not a sprint; it’s a marathon. It’s going to be a long process of working together and having the support needed to help everybody rise.”