Breaking the chain of infection one call at a time

UCI’s leading-edge contact tracing program has helped control the coronavirus’s spread on campus and in the community

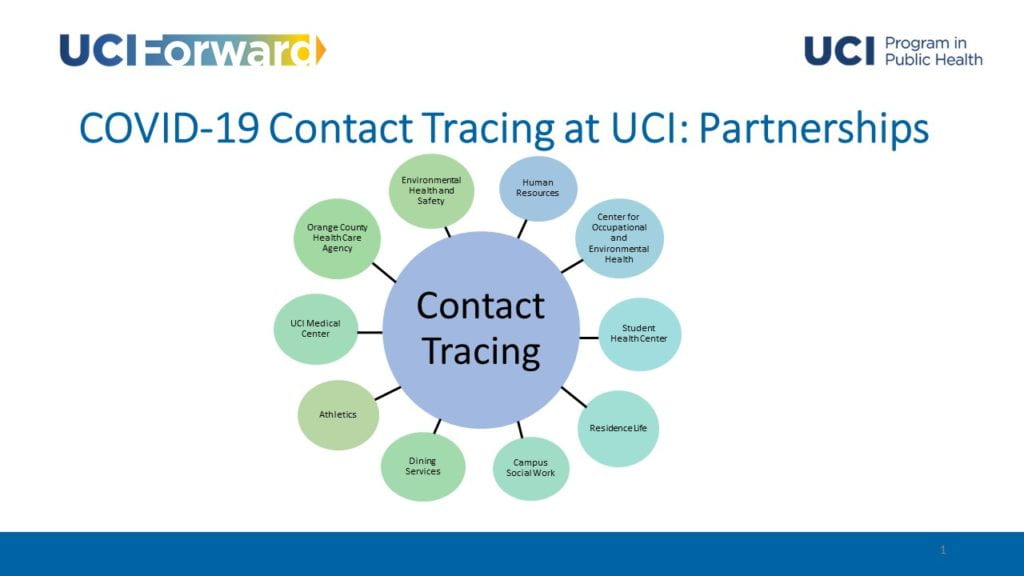

Contact tracing – following the spread of infection from one person to the next – is crucial to containing COVID-19. An early adopter, UCI established a robust contact tracing program on campus that has helped prevent a major outbreak. With a resident student population of 7,000 when the academic year began, the university embarked on an ambitious, two-pronged effort to tamp down the virus: weekly asymptomatic testing for resident students and a contact tracing program unique to the UCI community.

“Our goal with contact tracing is to break the chain of infection and slow down the spread of the disease,” says David Souleles, director of the campus’s COVID-19 response team. “Contact tracing is a tried-and-true public health tool that’s been used for decades for many different types of communicable diseases.”

When someone tests positive for COVID-19, the contact tracing program staff reaches out via phone call. If the individual has not been told the test result by a healthcare provider, the contact tracer will inform him or her and conduct a detailed interview to try to determine the source of exposure as well as close contacts – defined as those being within 6 feet of a COVID-19-positive person for 15 or more total minutes within a 24-hour period. Tracers will then call each of the close contacts to interview them and provide quarantine instructions.

“A challenging part of the job is having to provide a student or faculty or staff member with their test results,” says UCI contact tracer Ryan Morinaka. “When I’m making a call, I don’t know how that person is going to react to hearing the news of being positive because that person may or may not know how they were exposed. When providing someone the results, I like to take the contact tracing element out of the initial call and just be me and talk to the person. Finding out that you’re positive can be something to take in, and I want the person to know that I’m here to help them through that before going into the interview process.”

Tracers also assess what positive cases and close contacts may need to successfully isolate or quarantine and work with campus resources to address those needs. With resident students, for example, they might consult with housing officials to ensure that food requirements are being met. Or if a student is living in an off-campus environment that doesn’t effectively support quarantining, UCI social workers may step in to bring him or her onto campus to occupy one of the 729 rooms the university has set aside for isolation and quarantine.

“One aspect of our program that makes us successful is our ability to respond in a timely way,” Souleles says. “That starts with getting asymptomatic and symptomatic test results back from UCI labs within 24 to 36 hours and then having a contact tracer immediately reach out to isolate the case, identify close contacts, and interview and quarantine them. Being able to do this quickly is critical to being able to break the chain of infection.”

An alumnus, Souleles began his career at UCI as an HIV educator in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Prior to returning to campus last August as director of the COVID-19 response team, he served in various leadership roles both as a governor appointee in the California Department of Health Services and at the Orange County Health Care Agency, where Souleles was deputy agency director and director of public health services. All told, he’s brought more than three decades of public health expertise to UCI.

With those connections, Souleles helped bridge UCI’s and the county’s efforts on contact tracing: The two entities entered into a memorandum of understanding that provides a UCI program with the authority to conduct contact tracing for the campus population.

UCI’s contact tracing team must report positive cases and information about close contacts to OCHCA, and the two groups coordinate on ongoing investigations, especially when contacts extend off campus – when, for example, UCI identifies students with COVID-19 who work or have attended family get-togethers off campus.

“For us, it has been less about the superspreader events that impacted other campuses early on and more about smaller gatherings and interactions,” Souleles says.

UCI has also helped local health authorities expand their contact tracing capabilities, beginning with a community forum that drew at least 700 people. In a 10-week, online summer workshop, the university trained more than 400 contact tracers, including about 30 people from OCHCA and over 150 UCI students.

“This was done with an eye toward health equity,” says Bernadette Boden-Albala, director and founding dean of UCI’s Program in Public Health. “It sets our training apart from all others.”

The workshop taught basic epidemiology and the mechanics of contact tracing, while focusing on ensuring health equity by partnering with groups that represent and work in the areas hardest hit by the pandemic. In particular, it trained tracers who speak Spanish and serve disproportionately affected Latino communities in Orange County.

As part of the workshop, the university created a fellowship program and allocated funding for 125 graduate students to learn how to become COVID-19 contact tracers, awarding them $5,000 each. After 10 weeks of online instruction, the fellows were certified at the same level as county health workers.

Even as more people get vaccinated, Souleles and his staff are continuing to monitor the status of the pandemic, current case rates throughout the county and the campus positivity rate. In the recent winter surge, the contact tracing team went from five to nine cases a day to about 30. More tracers joined the cohort to meet the demand, and they were able to continue reaching out to all those who tested positive and their close contacts the same day. Currently, UCI has 22 contact tracers working almost around the clock, but the team is ready to add staff if needed. There are about 150 trained fellows, graduate student volunteers and members of the student-run Anteater Emergency Medical Services group prepared to step up.

“Before joining the contact tracing program, I did not have any interest in public health, but since joining and understanding how I’m making a difference in the community, it has definitely piqued my interest in public health,” Morinaka says. “Contact tracing is truly a team effort in being able to provide the community with the support needed during this time. Being a part of this team and the UCI family is very rewarding, and what we’re doing is important.”

Souleles is optimistic about the future.

“We have the ability to control this – we really do,” he says. “Contact tracing and testing are important, but those simple everyday actions that students and staff and faculty can take that we’ve all heard over and over again are as important, if not more so, as the testing and contact tracing in really reducing the spread of infection.”