UCI scientists see order in complex patterns of river deltas

Landforms ‘self-organize’ to withstand human and natural disturbances

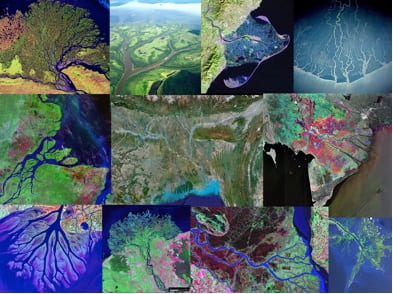

Irvine, Calif., Oct. 18, 2017 – River deltas, with their intricate networks of waterways, coastal barrier islands, wetlands and estuaries, often appear to have been formed by random processes, but scientists at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions see order in the apparent chaos.

Through field studies and mathematical modeling, they have concluded that deltas “self-organize” to increase the number, direction and size – or diversity – of sediment transport pathways to the shoreline, boosting their ability to withstand human disturbances and naturally occurring factors. The research team’s findings have been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“With their entangled channels that split and rejoin multiple times before entering the sea, deltas are amazingly complex and varied, leading us to wonder if they’re hiding some simpler order,” said lead author Alejandro Tejedor, research associate in UCI’s Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering. “Could there be some common ‘goal’ on the part of deltas to sustain their existence by diversifying the spread of their fluxes to build land on their way to the ocean?”

The researchers sought to solve this riddle by applying statistics and mathematical modeling. Looking at 10 major river deltas around the world, they determined the probability of flows dividing into smaller channels and merging again at confluences, discovering that all but one, the Niger Delta in Africa, exhibited a high “nonlocal entropy rate,” meaning a large diversity of delivery pathways to the sea.

The team confirmed these findings through numerical models, demonstrating that even when major channel avulsions take place – leading to network reorganization – flows tend to re-create diverse water routes.

“By adopting concepts from information theory, we showed that a range of deltas from different environments obey an ‘optimality principle’ that suggests a universality across almost every natural occurrence of these landforms,” Tejedor said.

Many of the world’s deltas have come under threat in recent decades from rising sea levels, local development and the construction of upstream dams that limit the flow of sediment.

“River deltas occupy only 1 percent of the world’s land surface but are home to more than half a billion people and are the source of vast amounts of food and other natural resources,” said Efi Foufoula-Georgiou, Distinguished Professor of civil & environmental engineering at UCI, who directed and co-authored the PNAS study. “So it’s imperative that we establish a better understanding of these vital earthscapes and how human and climate stressors might adversely impact their self-maintenance.”

Foufoula-Georgiou’s research group has been studying the mathematics of deltas for the past several years. Some of the work has been done in collaboration with Tryphon Georgiou, UCI professor of mechanical & aerospace engineering, an expert in information theory who is also a co-author on the PNAS paper.

This project, which was funded by the National Science Foundation, included scientists from Indiana University Bloomington; the University of Nevada, Reno; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne; and Italy’s University of Padua.

About the University of California, Irvine: Founded in 1965, UCI is the youngest member of the prestigious Association of American Universities. The campus has produced three Nobel laureates and is known for its academic achievement, premier research, innovation and anteater mascot. Led by Chancellor Howard Gillman, UCI has more than 30,000 students and offers 192 degree programs. It’s located in one of the world’s safest and most economically vibrant communities and is Orange County’s second-largest employer, contributing $5 billion annually to the local economy. For more on UCI, visit www.uci.edu.

Media access: Radio programs/stations may, for a fee, use an on-campus ISDN line to interview UCI faculty and experts, subject to availability and university approval. For more UCI news, visit wp.communications.uci.edu. Additional resources for journalists may be found at communications.uci.edu/for-journalists.