Forging ahead in the fight against hemochromatosis

Christine and Gordon McLaren’s research advances are improving the prognosis for a hereditary blood-iron overload disorder

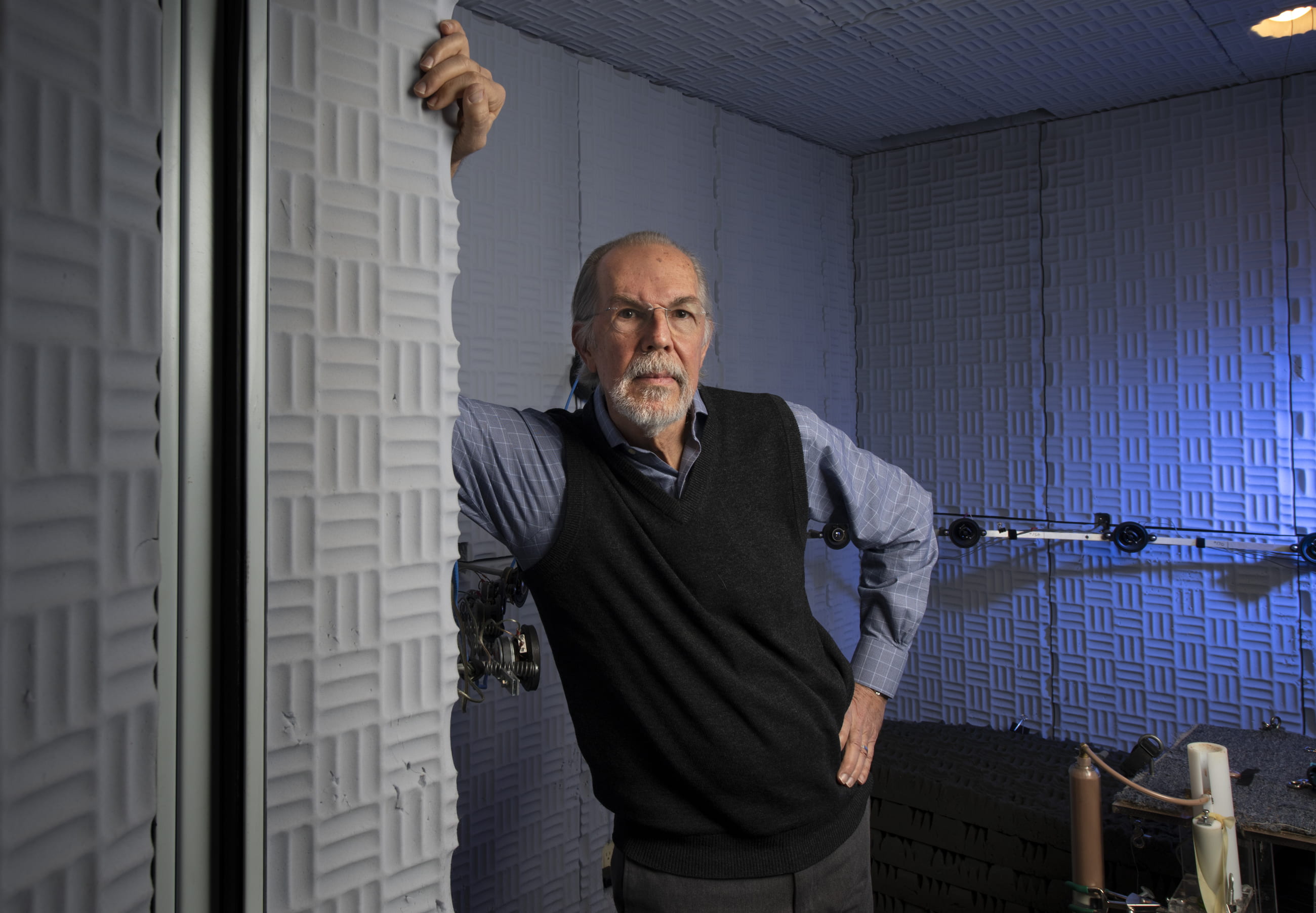

Since coming to the UC Irvine School of Medicine in 1998, Christine and Gordon McLaren have been leading the way in the research and treatment of hemochromatosis, a hereditary disease that causes the body to absorb too much iron from ingested food.

The excess iron is stored in various organs – especially the liver, heart and pancreas – and can poison them, precipitating such life-threatening conditions as cirrhosis and liver cancer, heart arrhythmias and diabetes. Once considered a rare disease, hemochromatosis is now recognized as one of the most common inherited disorders, affecting as many as 1 million people in the U.S.

Christine McLaren is a professor of epidemiology, and Dr. Gordon McLaren is a professor of medicine specializing in hematology and oncology who practices in the Veterans Affairs Long Beach Healthcare System.

Over the past few months, the wife and husband have made noteworthy strides: Last September, they received a $2 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases to investigate the genetic modifiers of iron status in hemochromatosis. And a study the McLarens presented in December at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology was a “Best of ASH” honoree.

Here, they discuss their work:

How did you both acquire an interest in this field?

Christine: We developed a focus on the disorder independently. Early in my career, I provided statistical consulting for hematologists who had research projects involving iron overload and iron deficiency. Meanwhile, Gordon has had a long-standing interest for over 30 years in the area of iron metabolism, with an emphasis on hemochromatosis.

In 2000, after Gordon and I had joined the faculty at UCI, we were fortunate to receive National Institutes of Health funding to work together and to screen more than 20,000 primary care patients for iron overload and hereditary hemochromatosis at UCI ambulatory care clinics.

The primary goal of that research was to contribute to a national epidemiologic study of iron overload and hereditary hemochromatosis in a multicenter, multiethnic, primary care-based sample of over 100,000 people.

How are people susceptible to hemochromatosis?

Gordon: Generally, iron overload occurs only in people with two copies of the hemochromatosis gene (one copy inherited from each parent). The frequency of having two copies in the European-American population is about five per 1,000 persons.

However, not all people with two copies of the gene will develop iron overload. Thus, we think there must be other factors – such as mutations in other genes affecting dietary iron absorption – that are required for the disease to become fully manifest, and this is what we’re studying.

If we can identify what causes the difference, we may be able to use this information to predict which patients are at greater risk of developing iron overload and when to begin therapy to remove excess iron before it accumulates to toxic levels.

Interestingly, the frequency of the genetic predisposition to hemochromatosis among European-Americans is the same in men and women, but for reasons that are not completely understood, men are more likely to develop the full-blown syndrome.

What do you plan to accomplish with the $2 million in support from the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases?

Gordon: We’re leading a multidisciplinary team of investigators at eight research institutions in the U.S., Canada and Australia. To better understand the reasons for this variability in disease expression, our group will examine genetic factors in the susceptibility or resistance to iron overload in patients with a genetic predisposition for hemochromatosis across a wide range of geographic areas.

The purpose of this research is to identify other inherited traits that may interact to cause more severe disease in certain patients. It’s important to identify persons at risk because effective iron removal treatment is available, and beginning such therapy before iron overload becomes advanced can prevent disease complications.

Christine: This work can have important clinical applications, including the ability to identify young hemochromatosis patients at risk for potentially severe iron overload later in life, thereby influencing physicians’ recommendations for iron removal therapy and long-term follow-up. We’re hopeful that our findings will lead to new approaches that will inform the development of innovative prevention and treatment strategies tailored to the individual.