The spooky side of science

In the spirit of Halloween, we offer a witches’ brew of peculiar probes and freaky findings by UCI researchers

Hundreds of researchers at UC Irvine work diligently to make discoveries that can literally change the world and how we see it. But some of their projects are, well, just a little bit creepy.

We’re talking psychopathic killers, zombies and aliens here. Ink-squirting squid, poisonous sea anemones and limb-regenerating Mexican salamanders. And ghosts that haunt Facebook.

In the spirit of the Halloween season, here’s a look at some of the work on campus that’s off the beaten path.

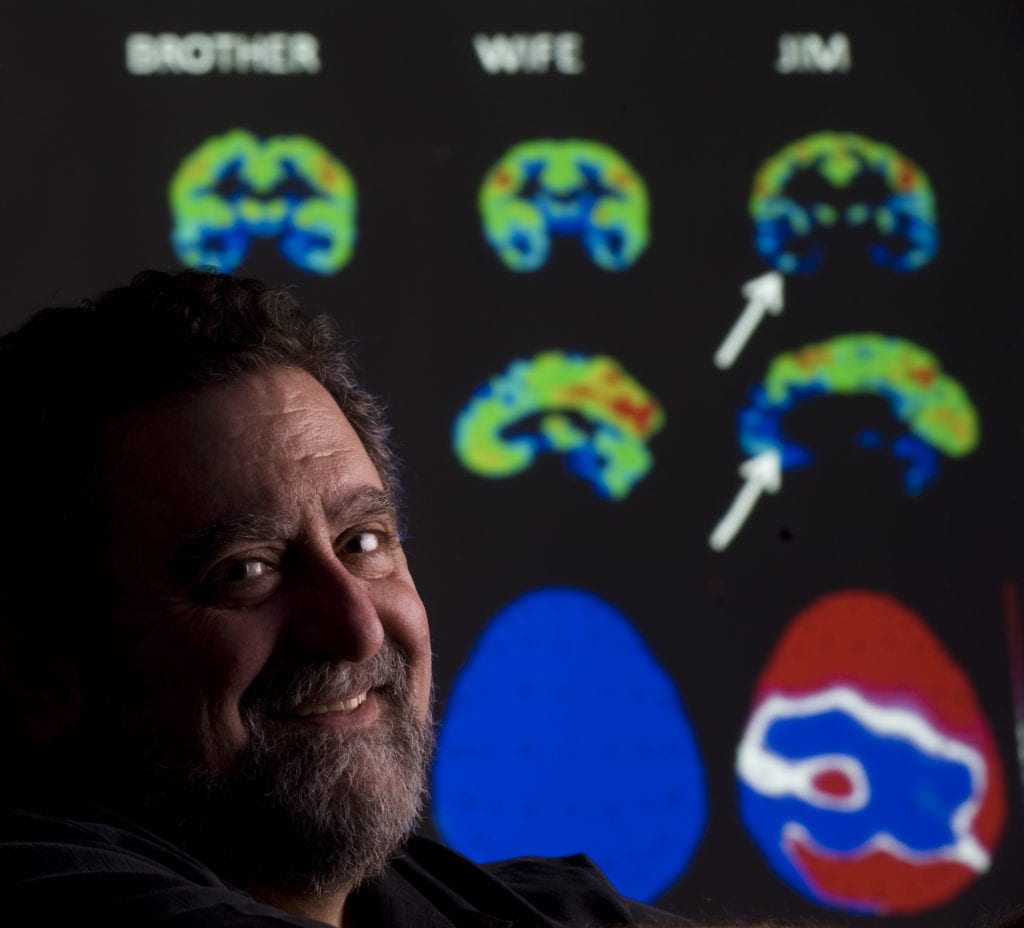

Finding the killer instinct … within: Neurobiologist James Fallon has led projects that shed light on everything from Alzheimer’s disease to Parkinson’s. He’s also one of the first researchers in the world to study stem cells in the brain. But his probe into the genetic brain patterns of convicted killers hit too close to home.

His family history includes eight rumored killers, and Fallon was curious about which of his living relatives might be genetically predisposed to murder. “I wanted to see … who the ‘evil’ one was lurking in our midst,” he says. “The joke was on me. It turned out I was the ruffian. I have the exact brain pattern of a psychopathic killer.”

Scans showed that his orbital cortex – the gray matter believed to be involved in social adjustment, ethics, morality, and the suppression of impulsivity and hostility – is inactive, as it is in many criminals. Fallon also has all five major gene variants linked to aggression.

So why isn’t he an ax murderer? Nurture has triumphed over nature. Fallon lacks a third factor common among killers: early exposure to violence or severe abuse. “I had a charmed childhood; I was never abused. No one’s done anything bad enough to turn me into a killer,” he says. “It shows that your genes are not a jail sentence.”

Fallon hopes his research will promote greater understanding of the mentally ill – and that, through positive parenting and compassionate public policies, families and society can avoid creating monsters.

Studying genes and aggression “gets people thinking about the biological bases of behavior,” he says. “Most killers can’t help it, so the nurturing component is crucial. There’s a message here: Treat your kids and your culture well.”

The search for frugal aliens: To those scanning the skies for signs of extraterrestrial life, physicist Gregory Benford offers this advice: Look for the frugal ones.

In reviewing the SETI effort to find distant alien signals, he and his twin brother, James, and James’ grandson Dominic – all scientists – looked at the issue from “the point of view of the guys paying the bills,”ory Benford says. “Whatever the life form, evolution selects for economy of resources. Broadcasting is expensive, and transmitting signals across light-years would require considerable resources.”

Assuming that an alien civilization would strive to optimize costs, limit waste and make its signaling technology more efficient, the Benfords proposed that these signals would not be continuously blasted out in all directions but rather would be pulsed, narrowly directed and broadband in the 1-to-10-gigahertz range.

“This approach is more like Twitter and less like War and Peace,” notes James Benford, founder and president of Microwave Sciences Inc. in Lafayette, Calif.

The trio and a growing number of other scientists involved in the hunt for extraterrestrial life advocate adjusting SETI receivers – which are focused on narrow-band input – to maximize their ability to detect direct, broadband beacon blasts.

“Will searching for distant messages work? Is there intelligent life out there?” Gregory Benford asks. “The SETI effort is worth continuing, but our common-sense approach seems more likely to answer those questions.”

“Walking Dead” MOOC: When the idea for a massive open online course – a MOOC – exploring issues related to the hit television series “The Walking Dead” came to life, a multidisciplinary team of UC Irvine faculty jumped at the chance to teach it. Zuzana Bic in public health, Joanne Christopherson in social sciences, Michael Dennin in physics and Sarah Eichhorn in mathematics had experience teaching MOOCs, a history of using pop culture in the classroom, and a strong curricular alignment with case studies from the television show.

The course, titled “Society, Science, Survival: Lessons from AMC’s ‘The Walking Dead,’” began Oct. 14, the day after the series’ Season 4 premiere, and runs for eight consecutive Mondays through Dec. 2. The UC Irvine professors gladly stepped out of their comfort zone to teach concepts peripheral to show topics.

“I never imagined as a mathematician that I would be teaching a course about zombies,” Eichhorn says. “Surprisingly, there is actually a lot of interesting math related to ‘The Walking Dead.’”

Dennin has long been interested in science outreach. He has appeared on numerous specials for the National Geographic and History channels, including “The Science of Superman,” “Batman Tech,” “Spider-Man Tech” and “Star Wars Tech.”

“This combination of popular science fiction and actual science education is an incredibly powerful mix,” Dennin says. “The opportunity to combine an online open course with a popular television show is a natural pairing. It brings together an audience with a basic interest in science – whether they realize it or not – and a raw curiosity about what is possible.”

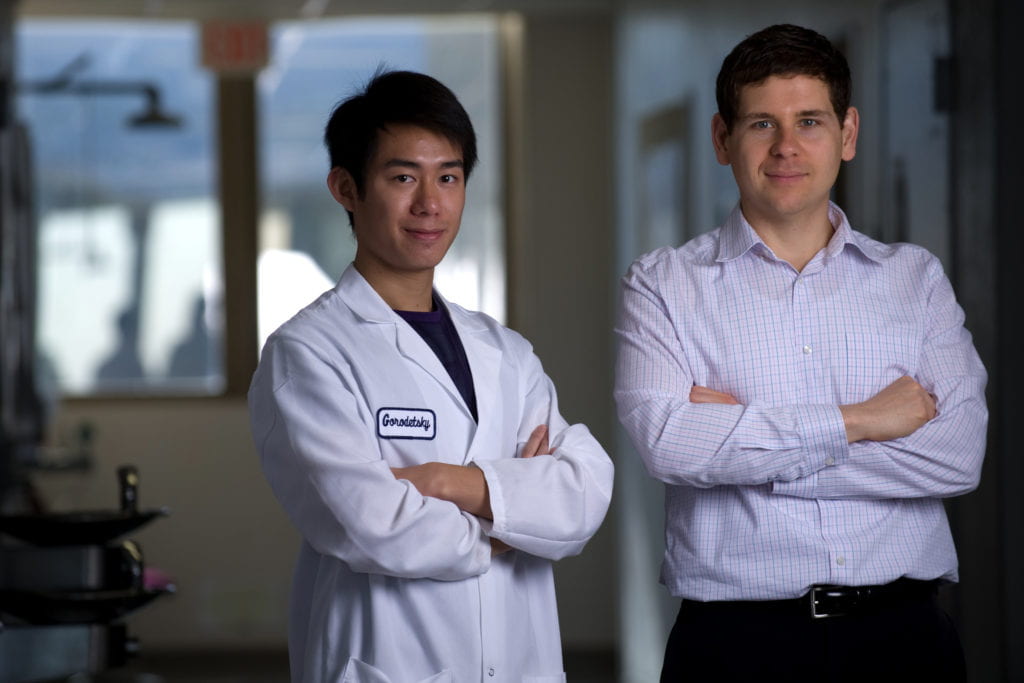

Squid, sea anemones and salamanders … oh, my: Our underwater friends have been the focus of some groundbreaking research at UC Irvine, even if they’re not for the squeamish. Anyone who saw the giant squid attack in the film “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” as a child may have serious reservations. But UC Irvine engineer Alon Gorodetsky and colleagues have used a structural protein essential in the squid’s ability to change color and reflect light to create a biomimetic infrared camouflage coating that’s invisible to infrared cameras.

And as colorful as they are, sea anemones aren’t so nice; they prey on small fish and shrimp by injecting them with a paralyzing toxin. Physiology & biophysics professors George Chandy and Michael Cahalan have developed a compound derived from this toxin that’s the basis of a new drug currently in clinical trials for the treatment of metabolic syndrome and autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Earlier this year, the researchers published study results showing the compound’s anti-obesity effects.

Lastly, you can chop a limb off of a Mexican salamander, but you can’t keep one down for long. Developmental biologists Susan Bryant and David Gardiner have long studied the lake-dwelling axolotl for its amazing and unique ability to grow back severed limbs. What they’re learning may one day be applied to humans.

The ghosts of Facebook: Although we all one day will shuffle off this mortal coil, our digital identity will live on through our social networks. Jed Brubaker, a Ph.D. candidate in informatics, explores why “to be, or not to be” is no longer a question.

“The mass adoption of social network sites includes, as a natural consequence, the growing presence of profiles representing individuals who are no longer alive,” he explains on his website.

“However, the death of a user does not result in the elimination of his or her account nor the profile’s place inside a network of digital peers. Indeed, the fact that friends use a user’s profile page, postmortem, to say last goodbyes, share memories and coordinate funereal arrangements is well known, if not frequently discussed. Death plays an increasingly significant role, then, in the experience of social networking.”

Hamlet couldn’t have said it better.