When uncontrolled anger becomes a soldier’s enemy

Professor’s anger assessment tool predicts severity of PTSD in combat veterans.

Economic setbacks, work pressures and the annoyances of daily life – such as long lines and rush-hour traffic – can cause otherwise calm people to snap and lose their cool. But when anger begins to affect personal relationships, on-the-job performance and physical health, it’s time for an intervention.

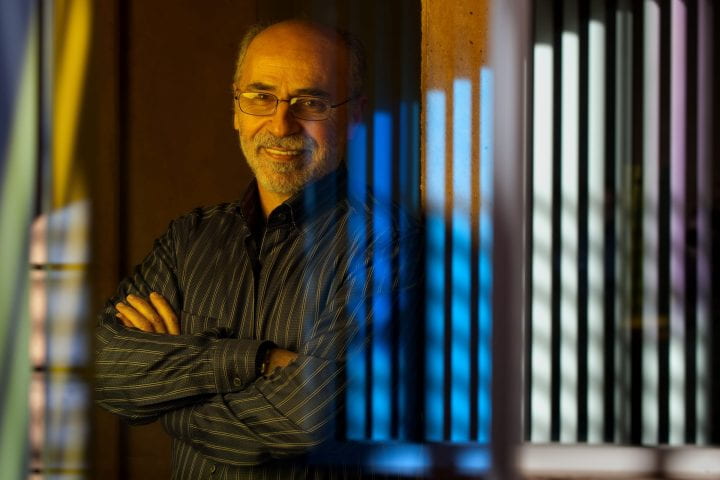

UC Irvine’s Raymond Novaco is a leading authority on the psychology of anger and violence. He pioneered the field of anger management in the 1970s, later extending that work to hospitalized patients and Vietnam combat veterans. Recently, he has applied his anger assessment research to soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

“A substantial number of our current war veterans have difficulty controlling their anger,” says Novaco, professor of psychology & social behavior. “This has serious implications for their ability to maintain supportive personal relationships and jobs.”

Researchers have found that 57 percent of combat veterans who used Veterans Affairs medical services experienced “more problems controlling anger since homecoming.” About 35 percent said they had “thoughts or concerns about hurting someone,” and of those diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, 84 percent reported greater difficulty in anger management.

Novaco recently developed and tested his seven-question screening tool that assesses anger among combat veterans and predicts their risk for violence and self-harm by measuring the frequency, intensity and duration of anger episodes and their psychosocial effects.

In collaboration with psychologists Rob Swanson, Mark Reger and Gregory Gahm at Madigan Army Medical Center in Fort Lewis, Washington, Novaco and graduate student Oscar Gonzalez used the questionnaire to evaluate more than 3,500 treatment-seeking soldiers who had served in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Study findings strongly validated the anger measure, including its association with functional impairments in relationships, job performance and coping skills, as well as with substance use. Novaco’s assessment tool was also conclusively related to the risk of harm to self or others, controlling for many background factors and symptoms of PTSD

and depression.

The results are published online (purchase required) in Psychological Assessment, a journal of the American Psychological Association, in advance of its printed issue.

“Anger is part of the human fabric, the emotional component of the fight-or-flight response to threats,” Novaco says. “It becomes a problem when it’s too frequent, too intense, lasts too long and activates violence.”

Managing anger is fundamentally about self-regulation, he notes, and starts with self-monitoring.

“Someone with a recurrent anger problem has a broken thermostat,” Novaco says. “One of the first goals in anger treatment is to boost self-monitoring capacity. The ability to recognize early physical signs of anger – such as tense muscles, rapid breathing and agitation – is an important step toward controlling it.”

The anger treatment that he developed and used in past work with Vietnam veterans is called “stress inoculation,” in which anger-provoking situations are simulated in imaginal and role-playing exposures. These graduated doses of stress produce “anger antibodies,” building coping skills and moderating the individual’s reactions in real-life scenarios.

Learning how to change one’s perceptions of upsetting situations, improving one’s problem-solving abilities and mastering arousal reduction techniques – breathing exercises and guided imagery, for example – are crucial to anger management, Novaco says.

He hopes his findings prompt greater attention to the assessment of anger in behavioral health evaluations of post-deployed service members. “For most veterans,” Novaco notes, “the cost of staying angry is a lot higher than the cost of trying to change.”