Nursing mind and memory

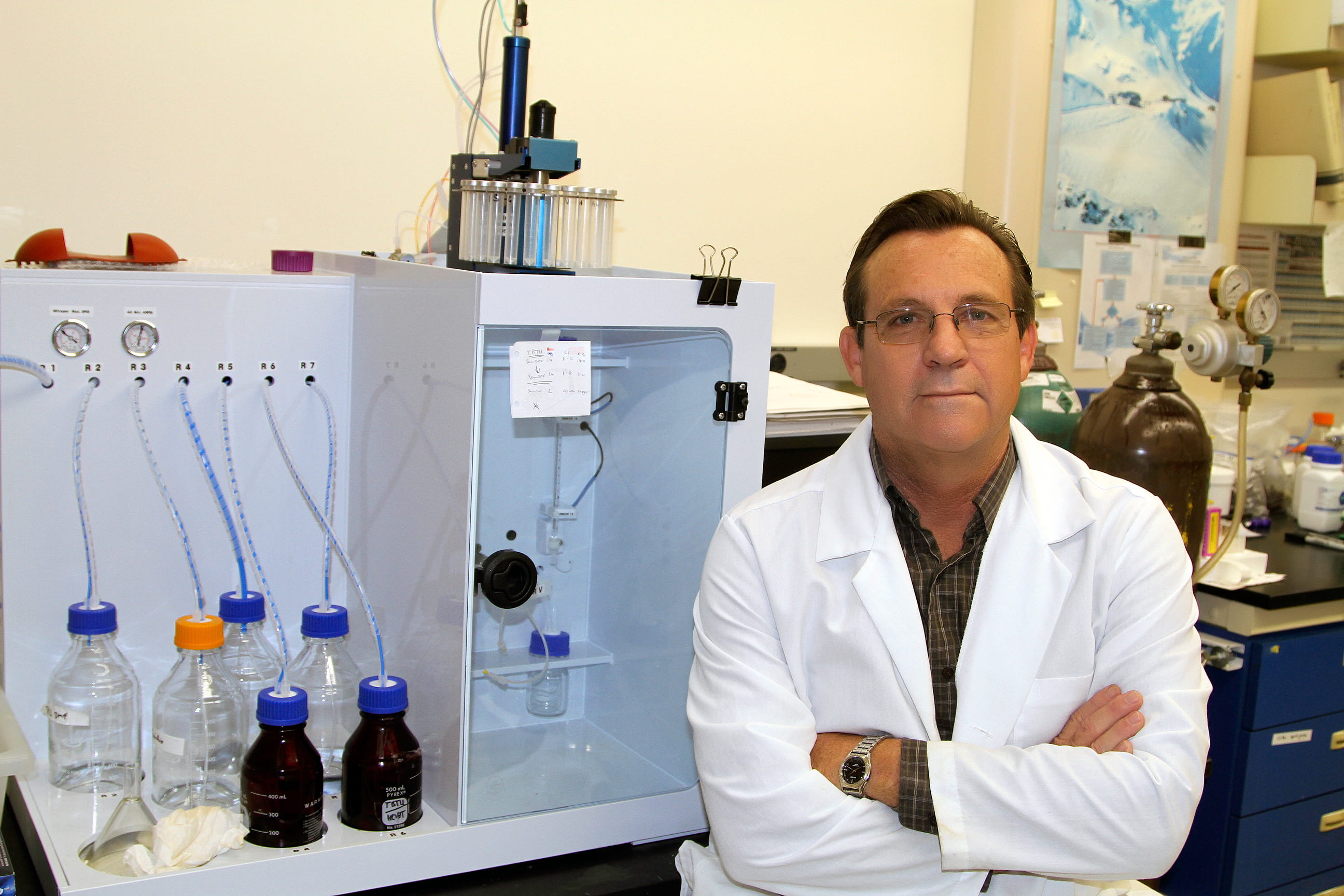

Ruth Mulnard, founding faculty member in UCI’s nursing science program, leads clinical trials to help Alzheimer’s patients.

From the instant Ruth Mulnard hit the neurosurgery floor as a newly graduated nurse, she knew her calling was neuroscience. She’d helped her teenage brother recover from a severe head injury, and she was sure she could assist people with similar needs.

With a subsequent master’s in neuroscience nursing from the University of Maryland, Mulnard came to UC Irvine Medical Center in 1988 to help open the neuroscience inpatient unit. Today, she directs clinical trials and other studies for the university’s Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders.

A founding faculty member of UCI’s Program in Nursing Science, Mulnard is especially proud of the curriculum’s emphasis on the science underlying patient care.

“Our students are getting the most rigorous nursing science education I’ve ever seen,” she says. “Our nurses will be able to think critically and understand the physiology of what is going on with patients, why specific medications and other interventions are appropriate as they strive to individualize patient care.”

Nurses are uniquely suited to conducting clinical trials, Mulnard says. Because they work so closely with patients, nurses with research training can observe, test and document the smallest reactions to drug trials.

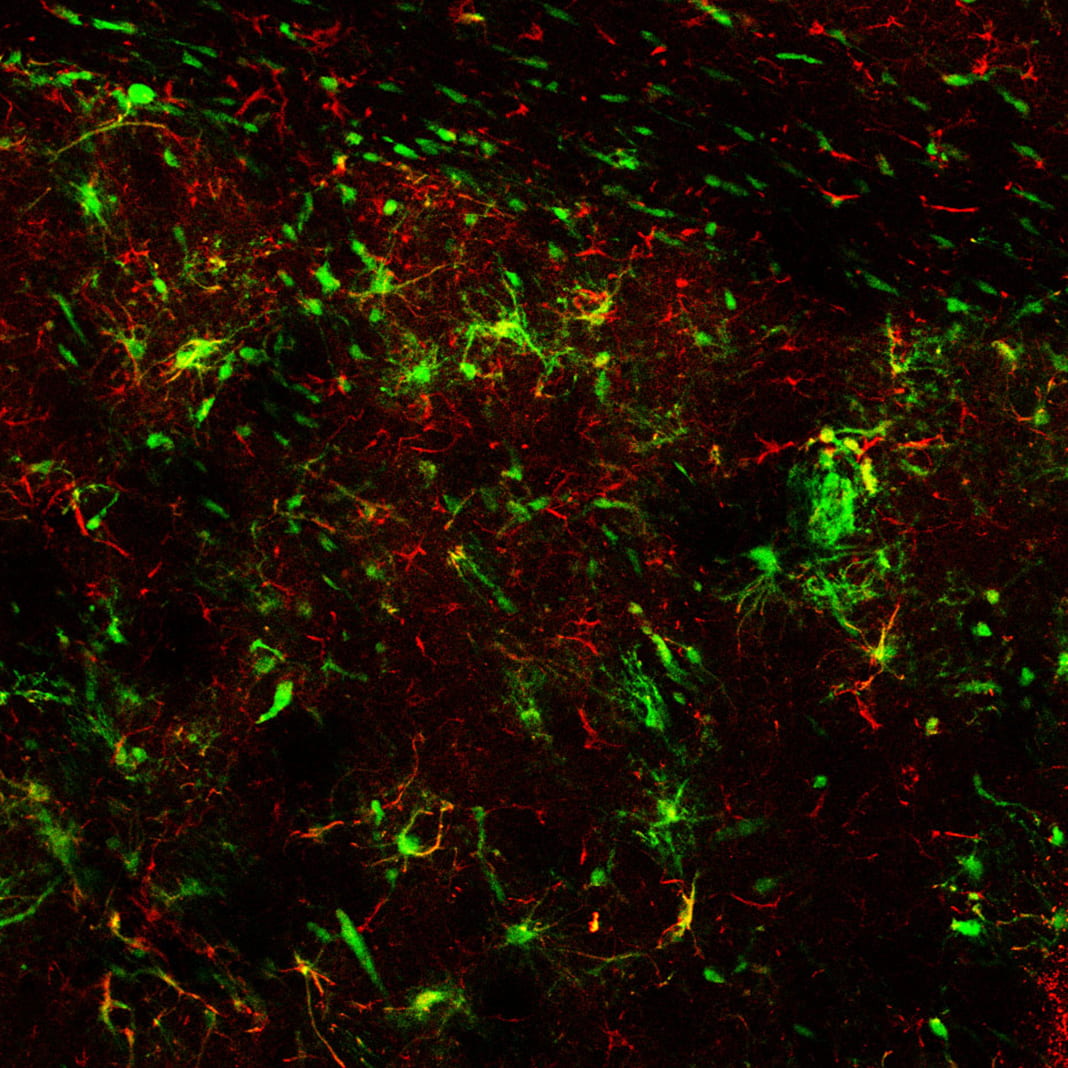

“A nurse-scientist bridges the gap between basic science and clinical science – the human side,” she says. “We investigate how discoveries from basic research apply to patients and how clinical problems can, in turn, influence basic science discoveries. The goal is to offer hope and make a difference in a patient’s life.”

One of Mulnard’s high-profile clinical trials studied the effects of estrogen replacement therapy on women with Alzheimer’s disease. She led researchers at 32 locations across the nation studying 120 women with mild to moderate symptoms. The women – all of whome were 60 or older and had previously had hysterectomies – were randomly assigned two different doses of estrogen or a placebo.

Smaller and shorter studies had shown estrogen to have positive effects on Alzheimer’s patients. But when the women showed no overall improvement in mood, memory or other areas of cognitive function at the end of the 15-month study, Mulnard alerted the Journal of the American Medical Association,, which published her findings in February 2000.

”I was able to convince JAMA to accept the research paper for fast-track publication in eight weeks. It was important to get the word out quickly, to diminish the use of estrogen in treating Alzheimer’s disease, which had proceeded without evidence.”

Later, Mulnard fought for a change in state law that authorized only a legal guardian or conservator to approve clinical trial participation for a patient unable to give informed consent.

“Unless our patients were in the earliest stage of dementia, they weren’t able to truly provide informed consent,” she recalls. When the law changed in 2003, Mulnard and two collaborators from UC San Diego received plaques and certificates from groups that focus on treatment and advocacy for the cognitively impaired.

Among other honors, Mulnard was selected as a Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing in 2007, and was appointed a founding member of the California Public Health Advisory Committee in 2008. She also is chair of one of UC Irvine’s Institutional Review Boards, which oversees research on human subjects.

Mulnard says her choice long ago to specialize in neuroscience research has been deeply satisfying. “My research team and I try to make a difference every day, to provide hope and purpose for our patients and their families in the fight against memory loss.”