Chinese medicine goes global

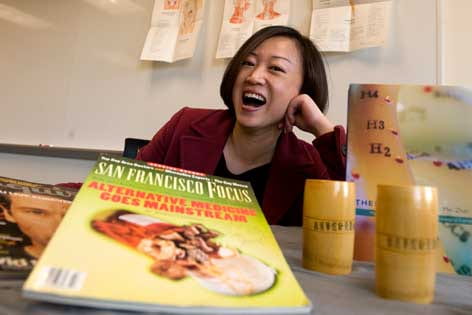

Anthropology professor studies evolution of traditional practice among rural poor into lucrative industry embraced by Americans.

Mei Zhan’s travels have taken her from medical schools in Shanghai to acupuncture clinics in San Francisco. For the past decade, she has traced the transformation of traditional Chinese medicine from its roots among China’s rural poor into a multibillion-dollar alternative-medicine industry.

A UC Irvine associate professor of anthropology, Zhan discusses the global influences behind this transformation in her new book, Other-Worldly: Making Chinese Medicine Through Transnational Frames.

“Chinese medicine is about much more than writing herbal prescriptions and inserting acupuncture needles,” Zhan says. “Today’s Chinese medicine treats ailments associated with a middle-class, urban lifestyle: chronic pain, insomnia, stress and anxiety.”

The use of herbs, acupuncture, aromatherapy and massage has become mainstream in the U.S. only over the last few decades; it wasn’t always this way. Acupuncture was illegal in California until 1975, and the first preventive application of Chinese medicine outside China was in Africa, not the U.S. or Europe.

In the 1960s through the early ’70s, China sent medical teams to rural villages in Africa to meet basic healthcare needs and prevent large-scale epidemics among the poor.

“At the time, China saw itself as a champion of the Third World and began exporting acupuncture as a way to assert its global presence and promote African-Chinese brotherhood,” Zhan says.

While Chinese medical teams were spreading the word in developing countries, American visitors to China in the 1970s were discovering the benefits of acupuncture and herbal medicine for themselves. In 1971, New York Times journalist James Reston’s acupuncture treatment after an emergency appendectomy in Beijing made front-page news in the U.S. and spurred public interest in alternative methods of pain relief.

American healthcare professionals inspired to travel to China to learn about such treatments were surprised to find medical students from Africa, Asia and Latin America already there, Zhan says.

By the 1980s, innovations in acupuncture and herbal medicine had shifted from Asia to the U.S. West Coast, especially the San Francisco Bay Area. Visits to practitioners of alternative medicine increased by 47 percent in the United States between 1990 and 1997.

In fact, Chinese medicine has become such an American phenomenon that builders of a “California-style” residential neighborhood in Shanghai touted the inclusion of an alternative-medicine clinic.

The irony is not lost on Zhan. “It’s fascinating to see Chinese developers capitalize on West Coast appeal by offering acupuncture to homeowners,” she says.