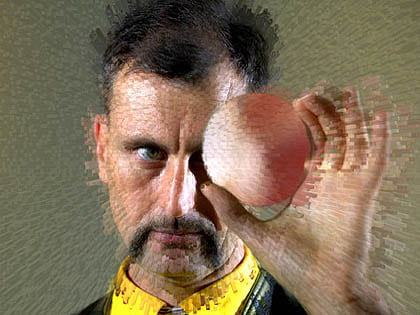

Pushing the edge

Self-described ‘gizmologist’ Simon Penny sees a new culture – and area of study – emerging from the digital age

Simon Penny believes society is on the edge of a change as resounding as the Industrial Revolution. He sees the emergence of a digital culture that blends art and technology into new social practices only now being imagined by Penny and others in his field.

Artist, engineer, researcher and teacher of interactive media art, Penny came to UCI from Carnegie Mellon University in 2001 to start a cross-disciplinary graduate program marrying these interests. As director of UCI’s ACE (Arts Computation Engineering) Graduate Program, which begins this fall, he holds a joint appointment as professor in the Claire Trevor School of the Arts and in The Henry Samueli School of Engineering. He is also leader of the New Media Arts Layer of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology [Cal-(IT)²], a research collaboration between UCI and UC San Diego.

Penny’s art installations have been exhibited in the United States, Europe and his native Australia. His latest work, “Body Electric,” was recently presented at the Williamson Gallery of the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Curator Stephen Nowlin says, “Penny’s work promotes a relationship between human and machine that’s different from the way we’re accustomed to sensing the world.”

uci.edu caught up with Penny to find out what this impending digital revolution – and his work – is all about.

Q. Are you an artist first or an engineer?

A. The two practices attend to different aspects of the work. I’m both and neither. One day I’m a cognitive scientist, or an ethnographic researcher, or a painter, or a tinkerer in a tool shed. The next day I’m involved in developing machine vision systems. My work demands that I practice and integrate all of those things.

Q. How does the shift toward a digital culture affect you as a teacher?

A. My educational mission is to build classes and programs that enable students to be well-rounded professionals in this new area – mixing computer science, the arts and engineering, plus elements of the humanities, social sciences and biosciences.

Among other things, I teach what I call ‘gizmology,’ which addresses the practical issues of how you make an interacting machine system that integrates electronics and mechanics. It’s relevant for artists doing kinetic sculpture or interactive museum exhibits, for instance, and for people interested in animatronics, or theme park design. In a sense, it’s an introduction to robotics. I also teach more historical, theoretical classes where we look at cognitive science, anthropology and the history of technology. Then we stitch it all together to produce a kind of ‘hybrid vigor.’

Q. What’s hybrid vigor?

A. It’s a term from genetics and our motto for the ACE program, reflecting how the combination of computer science, engineering and cultural studies inevitably produces something wild, vigorous and complex.

The ACE program is composed of three different master’s degrees – in engineering, computer science and the arts – but all of the candidates take the ACE core courses together.

Essentially, we’re examining interactivity – not just someone sitting at a computer poking buttons and pushing a mouse around, but what happens when 120 people all are working with handheld geo-positioned interactive devices, or when five people in different places operate in the same virtual reality environment. They might be playing a medieval battle simulation game or designing a new car.

This is profoundly new, exciting stuff. We don’t know what kind of art or cultural practices or technology will result. The sky is the limit.

Q. How does the Cal-(IT)² research come into play?

A. The agenda of Cal-(IT)² is to research communications and information technologies that will hit the market in 10 to 20 years. The arts layer is similarly forward-looking, studying emerging practices such as multi-user, role-playing game environments, and seeing how we can adapt these environments to education, research or disaster management practices, for example. I hope that ultimately the ACE program and the arts layer – along with UCI’s Beall Center for Art and Technology – will function together to prototype emerging digital practices and train a new generation of professionals.

Q. Where do the artist, researcher, teacher and tinkerer in you converge?

A. I try to integrate the way we are as people into these new digital technologies. Industry and academic research have not addressed this issue very well. We still sit hunched over, staring at a flickering screen because we’re forced to encode our thoughts in ways digestible by the machine. I would like to see computational systems that understand more of the complex dynamics of human behavior.

In ‘Body Electric,’ the installation I created with Malcolm McIver of Caltech, the viewer doesn’t get the sense of interacting with a lot of computer technology. Via a multi-camera machine vision system with real-time 3-D computer graphics, the viewer plays the role of a fish that ‘sees’ its prey through a self-generated electric field.

There is a largely undocumented history of artists prototyping new media technologies decades ahead of the curve. The conventional assumption is that artists may come into a research program at the end and make it pretty. I believe that artists are most valuable in the blue-sky, first-cut envisioning of new technologies. My colleagues and I at UCI and elsewhere are forging a new range of specializations. There are centers and edges to all disciplines; we’re just defining a different center and a different set of edges.